The Internet Institute

'At the dawn of the millennium we had a world in which just over 5% of humanity was connected to the Internet. Only 15 years later, we are approaching a world in which the majority of the population has access. The vast majority of these new connections are in low- and middle-income countries.'

I’m speaking to Mark Graham, Senior Research Fellow and Associate Professor at the Oxford Internet Institute. Mark starts our conversation by describing the vast global network that is the internet. The story he tells is of an American Dream style ideal – where anyone connected to the internet can make use of it, equally. But the reality, as he goes on to describe, is much more complicated.

'This rapid transformation of connectivity has encouraged politicians, journalists, academics and citizens to speak of an ICT-fuelled "revolution" happening in the developing world. Individuals and firms would increasingly be linked into global networks – interacting, selling and using knowledge through this connectivity.

'This has led to a lot of hopes that the internet will reduce some of the information-based advantages that dominant economic actors have had. Open marketplaces, for instance, offer the potential to cut out the middlemen (or "intermediaries") in commodity chains. Open information about market prices similarly makes it more difficult for intermediaries to exploit farmers and producers of products.

Despite the fact that anyone with an internet connection can edit Wikipedia, European internet users are far more likely to do so than African ones.

'However, some of our research based at the Internet Institute shows that many of these hopes are unfortunately not being fully realised. We see that greater connectivity is a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for active online engagement: for instance, despite the fact that anyone with an internet connection can edit Wikipedia, European internet users are far more likely to do so than African ones. So, yes – plenty of information is open now, and plenty is accessible. But that doesn’t mean that everyone has equal voice, representation or participation in that information: something our research starkly shows. And while it might seem that the internet might or could level the playing field, that has not necessarily happened.

'What we often forget is that the middlemen, the intermediaries, can add substantial value to any process. So what we have seen emerging is increasingly powerful networks: Google, Facebook, Amazon, "infomediaries" (they mediate information) which end up shaping much of what we do, know and buy.

Think about the way that Google (the platform that mediates most of our searches for information) works. If lots of pages contain links to a page, that page becomes more visible via Google. This can create virtuous and vicious cycles of information: the already visible becomes more visible.'

What are the risk of digital monopolies – do you think more attention should be given to the politics of the big players (Google buying YouTube, Facebook buying Instagram etc., and how that affects the digital landscape and even the autonomy of smaller networks)?

'The digital monopolies that have emerged – like Google in the realm of search and Facebook in the realm of social media – are, in many ways, useful because they can offer us a seemingly complete picture of the world. Yet that is precisely what makes them dangerous. Within those platforms, opaque algorithms are employed to make some information visible and some invisible. And the consequences of being omitted from Google results and Facebook are not just informational, but also economic, social and political. Yes, those companies are efficient and innovative and undoubtedly make our lives easier. But do we want to place so much of our trust into them?

'I’m not saying that these sorts of concentrations of power are anything new; but rather we are not seeing the sort of democratisation that many suggest a web of 3 billion connected people could bring about. Yet, it is precisely because the web’s possibilities for something different that we should be encouraged to look for alternate digital models.'

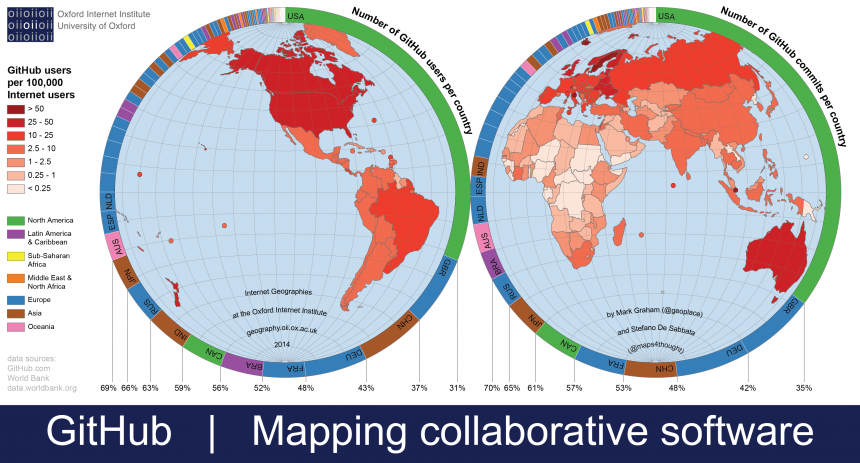

Git Hub

Git Hub

What, do you think, is the importance of the internet to us as citizens?

The internet has been at its most important when it is used as a way to challenge power.

'The internet has been at its most important when it is used as a way to challenge power. Whether that is exposing information about torture, illegal wars or military occupations; whether it is challenging unjust and exploitative configurations of global production networks; or simply bypassing or transcending otherwise previously prohibitive barriers to flows of information.

'But this doesn’t mean that the network itself can’t also reinforce and amplify power mediated through it. There are ample examples of the ways that the internet allows for more effective control and manipulation. Like any tool, the internet can often be used most successfully by the wealthiest, the loudest and the most powerful to achieve their own ends rather than to challenge injustices and inequalities.

'The most important thing we should be doing, then, is asking how we can learn from any successful digitally mediated subversions of power. That we make sure we don’t just see the internet as a tool that allows us to buy more, buy more quickly, buy more cheaply. Let’s never forget that we can shake the foundations of the world with it, and let’s remember that sometimes we might just need to.'

Tell me more about your project Wikichains (it describes itself as 'encouraging transparency in commodity chains').

'The Wikichains project started when I got tired of going into coffee shops and seeing glossy pictures on the walls of smiling workers in coffee plantations.

'The Wikichains project is an effort to use user-generated content to re-attach information about products to products themselves. Information like wages, worker conditions, environmental impacts, etc. Imagine being able to click on a product and seeing text, images and videos about where that product came from.

'The point of sharing all of this information is to present alternate stories about the things that we consume. Instead of being solely influenced by the photos and stories on the walls of the coffee shop, we can (easily) dig a little deeper to try to better understand whether we see anything distasteful in the geographies and histories of physical things. In other words, it allows us to behave more ethically as consumers in ways that potentially benefit producers and workers around the world.'

It’s been a thorough discussion of the complexity of the internet, and of debunking the hype of the internet ‘revolution’. How did you come to the Oxford Internet Institute (OII), and what does your general research focus on?

'I moved to the OII after spending a year working as a lecturer at Trinity College Dublin. At Trinity I taught classes on Human Geography and Economic Globalisation: thinking about what changing connectivities do to economic and social networks. But Oxford offered something different – a chance to work with a cluster of scholars that were doing cutting-edge research into the social, economic and political effects of the internet. It’s allowing me to hone my methodological work on mapping the geography of the internet, continue asking critical questions about who benefits from the internet in some of the world’s previously most disconnected places, and get to work with a great bunch of colleagues.'