Research to policy impact: strategies for translating findings into policy messages

Blog by Kay Jenkinson, Knowledge Exchange Specialist, Leverhulme Centre for Nature Recovery, University of Oxford; and Dr Sarah Higginson, Knowledge Exchange Specialist, Innovation and Engagement, Research Services, University of Oxford

For academics seeking to bridge the gap between their research and policy-making, the journey to impact can be both challenging and rewarding. The impact process is often nuanced, and marked by slow progress with occasional unexpected bursts of action and achievement. Rather annoyingly, it can be the casual interactions at events or a small action arising from a meeting that can lead to the greatest impact.

However, some fairly simple planning can help to ensure that you know the people you need to contact, have the right materials to engage them and are well-placed to contribute your evidence to (policy) discussions and development.

Until 2022, we both worked at the Centre for Research into Energy Demand Scenarios (CREDS, www.creds.ac.uk). This blog is based on a recent presentation we gave on some of the strategies and tips we used in CREDS to take this programme’s research to a wider audience of academics, practitioners and policymakers.

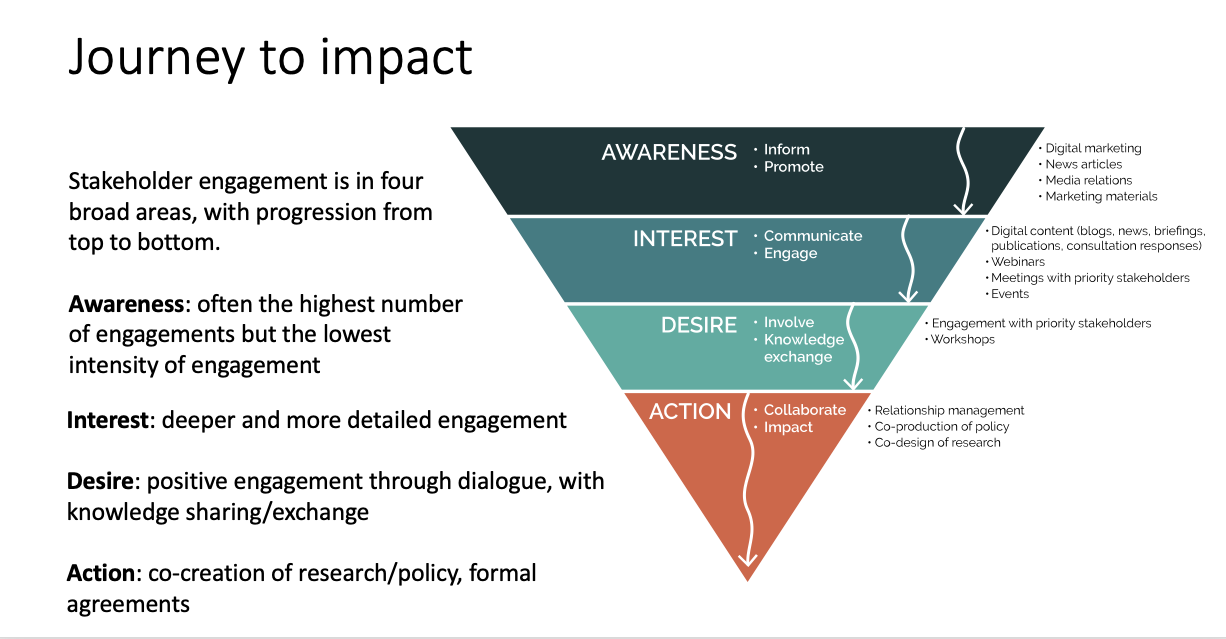

One can think about the process as a ‘journey to impact’ as decribed in the figure below. The ambition is to move stakeholders through awareness, interest and desire to action, which is where impact happens. As suggested by the funnel shape of the figure, the largest number of engagements with the largest number of people will happen at the start of this jouney and will involve fairly low-key methods focused on providing information and promoting the research, such as digital marketing and media outputs. Once stakeholders get interested, they will be ready to engage more deeply and may be ready to communicate with you, for example through digital content or coming to webinars. The next step is ‘desire’ which is where a relationship begins with priority stakeholders, involving dialogue and knowledge exchange. In the final step, where impact happens, relationships with stakeholders are well developed and collaborative. Research and/or policy might be co-produced and feed directly into one another. Clearly, by this stage, the number of people involved is iterative and emergent with many feedback loops. small and the work is detailed and specific. While this process is presented here as linear, it is in fact

Figure 1: Image source: CREDS guidance resources

To get started on this journey, you will need to set out a plan. To begin, work out who you need to talk to. Think about how they could make use of your findings. You may end up with a big list, also called a stakeholder map. In that case, tailor your work to the resources available and consider who the priority audiences are (they are probably in organisations or professional bodies but, ultimately, you are looking for named individuals) you want to reach. The aim is to talk to the groups of people most likely to be interested in your subject and your work.

Also think about your role in all this. Are you mediating between competing technologies or alternative approaches as an honest broker? Are you committed to a strategy and thus want to share all its benefits? How does this affect the people you speak to? How do they view you? How do you present your work? Bottom line is to stick to the evidence – that's our USP, our super-power.

Consider: is it better to invest in one contact and build a strong relationship with them to have a narrower but positive impact

Decide: Honest Broker or Enthusiastic Advocate? Researchers aim to be unbiased but realistically are biased toward their own research

Tip: It may be useful to link with an organisation already active in this space, such as an NGO, another University or a Think Tank. This does not affect your academic integrity, the evidence you present is the same, you are just sharing it with people who can be a channel for conveying it to policy makers.

With all of the above, make sure that you are communicating in ways that are timely, efficient, useful, accessible and open.

Some advice:

- Being clear about what you are offering, what your evidence is saying and why it is important are all things to strive to do.

- Write/present for non-academics as you are unlikely to be addressing a specialist. Check your assumptions carefully especially if there are technical elements, and avoid acronyms and terms that aren't widely used in public discourse (e.g. rainfall, not precipitation). It can feel scary stepping away from these useful tools, but you need to make yourself easily understood. Don’t just send a paper/report!

- Be clear about the strength of your evidence – avoid in-depth explanations of your methodology, but have that slide available in case you get asked. You need to be transparent, and be clear about uncertainties (e.g. give ranges)

- Try to consider your research in the context of the bigger picture that the civil servant is working in. For example, you might want to talk to them about flood risk in coastal communities, but local and national policymakers also have to consider the impact on regional health inequalities, or employment opportunities for school-leavers. You don't have to be an expert in these, but you could use some common sense to at least acknowledge these, and refer to co-benefits for these areas into your messaging.

One of the key success factors for policy engagement is timeliness. Timely information is very valuable to policy makers, but frustratingly, it's not always obvious when this time will be or there can be very little warning. That’s why it’s important to work on building relationships and positioning yourself so when your expertise is needed you are findable and familiar to key policy makers.

Don’t be afraid to be ‘human’ because even though you are an expert you are still asking people to connect with and build a relationship with YOU. It’s the personal that is memorable.

Tip: When you are at the beginning of your research consider the BIG CHANGE/key questions you want to answer, then consider who will care, then consider what value you could give them. Can you incorporate that thinking in your research process? And ideally can you reach out to that person to better understand how your proposed research could be of value to them, and what other factors you could consider when undertaking your research?

For more guidance on thinking about stakeholder engagement visit https://www.creds.ac.uk/theme/support/impact/