Features

As David Attenborough's Blue Planet II series on the BBC nears its conclusion, interest in our oceans is perhaps at an all-time high. One of the most memorable episodes focused on the world's coral reefs – in particular, the damage being caused by climate change.

This month, Oxford hosts the European Coral Reef Symposium, which will bring together experts from around the world to exchange ideas and discuss the latest developments in coral reef research, management and conservation. Tickets for the event – well over 500 of them – were booked up within weeks of its announcement.

The conference is organised by Reef Conservation UK (RCUK), along with the University of Oxford and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), with support from the International Society for Reef Studies. This year marks the 20th anniversary of RCUK, which was set up and is still run by early-career researchers with a passion for reef conservation.

Dr Catherine Head from Oxford's Department of Zoology is an RCUK committee member and one of the event’s organisers. She said: 'Coral reefs are on the frontline of climate change impact, suffering from major threats such as last year's climate-induced global coral bleaching, and the physical damage likely to be caused by this year's devastating hurricanes in the Caribbean.

'Meetings such as the European Coral Reef Symposium are crucial in bringing together the best minds in coral reef research and management to share findings and ideas to help tackle the threats to coral reefs while there is still time.'

A coral reef in the Maldives (Kirsty Richards)

A coral reef in the Maldives (Kirsty Richards)The UK has a greater direct stake in coral reefs than might be expected, with more than 60,000 km2 of coral reefs in the British Indian Ocean Territory alone. Globally, Europe hosts 7% of coral reefs within its territories – something that will be explored during the symposium.

And while researchers stress the scale and urgency of the threats to our reefs, they are also keen to emphasise that all is far from lost: popular social media hashtags such as #OceanOptimism highlight conservation success stories in an attempt to inspire new solutions. Meanwhile, the Great British Oceans coalition is campaigning to protect the waters around the UK's overseas territories.

Among the plenary speakers at the Oxford-hosted symposium, being held from 13-15 December, is Professor Madeleine van Oppen from the Australian Institute of Marine Science and the University of Melbourne. Professor van Oppen will be presenting her findings from a large project that is investigating whether species of coral can be cross-fertilised to increase their ability to withstand the effects of climate change, including higher sea temperatures. Looking ahead to the symposium, Professor van Oppen said: 'The focus on coral reef conservation and restoration is timely, as the decline of coral reefs is occurring at an alarming rate. Novel interventions to restore reefs and increase reef resilience are urgently needed.'

Other speakers include Professor Nikolaos Schizas from the University of Puerto Rico, and Professor Pete Edmunds from California State University, who have begun analysing the effects of hurricanes Maria and Irma on coral reefs in the Caribbean. High-profile scientists including Professor Morgan Pratchett from James Cook University in Australia – an expert on the Great Barrier Reef – will present their findings on the devastating, climate-induced bleaching events of the past two years.

Kirsty Richards, an RCUK committee member who is also ZSL's marine and freshwater programme coordinator, added: 'We are excited to have been asked to host the European Coral Reef Symposium in our 20th year – the largest gathering of coral reef researchers in the world in 2017. The interest in the event has been incredible.'

One of the world’s most celebrated mathematicians, Sir Andrew Wiles, is widely known as the man who cracked Fermat’s Last Theorem.

In 1994 Andrew’s proof catapulted him to international fame. He went on to earn some of mathematics’ highest honours, including the Abel Prize and a Copley Medal from the Royal Society. Both his peers and the wider world were gripped by his solving of what was widely believed to be an 'impossible' problem. In 1637 Fermat had stated that there are no whole number solutions to the equation xn + yn = zn when n is greater than 2, unless xyz=0. Fermat went on to claim that he had found a proof for the theorem, but said that the margin of the text he was making notes on was not wide enough to contain it.

At a rare public appearance earlier this week, at the Inaugural Oxford Mathematics London Public Lecture, held in the Science Museum, the audience were treated to revealing insight in to the man behind the maths.

Hosted by mathematician and broadcaster Dr Hannah Fry of University College London, the event featured a lecture followed by an interview including Andrew taking questions from the floor. In front of an audience that included the TV presenter Dara Ó Brian, Andrew addressed a range of questions and shared his thoughts and feelings on everything from his own personal career challenges to the role of maths in society at large.

Answering the question ‘is mathematical skill more nature than nurture?’ he drew a comparison with the film Good Will Hunting, which it is implied that if you are born with a natural aptitude for mathematics, it is easy. ‘There are some things that you are born with that might make it easier, but it is never easy", he said.

‘Mathematicians struggle with mathematics even more than the general public does. We really struggle. It’s hard. But we learn how to adapt to that struggle.’ Of his own struggles, Andrew revealed his belief in the ‘three Bs: Bus, bath and bed.’ Time when you can give into your subconscious and the mind is free to wander away from the immediate problem.

Asked by the comedian Dara Ó Brian, to describe his progress tackling Fermat’s problem, he compared it to three flagpoles in a row, ‘each one higher than the other’ but the ropes that join them ‘sort of sink’ with a ‘particularly big sag in the last one.’

Andrew also talked about his motivations. On the influences that drove his success in proving Fermat’s Last Theorem, and that continue to drive him today, he said: ‘I am always quite encouraged when people say something like: ‘You can’t do it that way.’

When asked his opinion on the skills required to be a great mathematician, he said that he believes that success in the field is more down to character than technical skill. ‘You need a particular kind of personality that will struggle with things, will focus and won’t give up.’ Sometimes the best young mathematicians can’t adapt to this need for struggle, he said. They want to solve things in days. Sometimes it takes much, much longer.

As a specialist in number theory, was he ever tempted to explore other mathematical fields? The answer was an unequivocal ‘no.’ He fell in love with his chosen specialism at a young age and his commitment has never wavered. ‘I confess that I was addicted to number theory from the time I was 10 years old and I have never found anything else in mathematics that appealed quite as much.’

When pressed as to whether his loyalty may be due to feeling less able in other areas, he added ‘definitely true.’

On the subject of exactly what it was that intrigued him most about Fermat’s theorem, he said that he was most captivated by the fact that Fermat wrote down the problem in a copy of a book of Greek Mathematics. ‘It was only found after his death by his son.’

He was so intrigued by the problem that as a student he would ‘sneak off to the library’ to read Fermat. But getting to grips with Fermat did not come easily to him. ‘He had this really irritating habit of writing in Latin.’ To this day Andrew’s Latin remains ‘minimal’.

Pressed on his view on one of the most challenging educational issues, the quality of and attitude towards mathematics at school and in the wider population, he cautioned that the issue is not that children are less interested in maths. ‘Most young people do have a real appetite for mathematics but they are put off by uninspiring teaching.’ When the teachers are not interested in the subjects they teach, it shows and rubs off and ‘gets passed on’ to their students. This is a particular problem at primary level where few of the teachers are mathematicians. As for a potential solution to the ongoing teaching crisis Andrew suggested ‘pay them more.’

Encouraging great mathematicians of the future, he advised them to tackle the ‘impossible problems’ while they were young (teens or undergraduates) and get a taste for research. But, they should buckle-down and ‘be responsible’ when they start their careers.

Andrew also discussed the Millennium Prize Problems, seven mathematical problems that were set by the Clay Mathematics Institute 17 years ago, offering $1 million dollar rewards for each one solved.

One of the problems, the Poincaré conjecture had already been solved in 2003, and of the remaining six, Andrew suggested the Riemann hypothesis is receiving the most attention. First identified by the German mathematician David Hilbert in 1900, the problem ‘says something about the way prime numbers are distributed’ a field where number theorists across the world have been collaborating with huge success over the past two decades.

Andrew shared his view of the beauty of mathematics and what this actually means. He compared solving a mathematical conundrum to walking down a path to explore a garden, designed by the great landscape architect Capability Brown and seeing a new and breathtaking view for the first time. The real thrill is in ‘this surprise element of suddenly seeing everything clarified and beautiful.’

But, like any thing of beauty, you should not stare at a mathematical problem for too long, otherwise ‘the majesty will fade, as is the case with great paintings and music.’ Instead, he prefers to ‘keep walking’ through the garden of mathematics, rediscovering his life’s passion, again and again.

This is the latest in the Artistic Licence series.

Growing up in Germany, studying in English, speaking Russian with her parents, and learning French in Belgium: languages have always been a central part of Swetlana Schuster’s life.

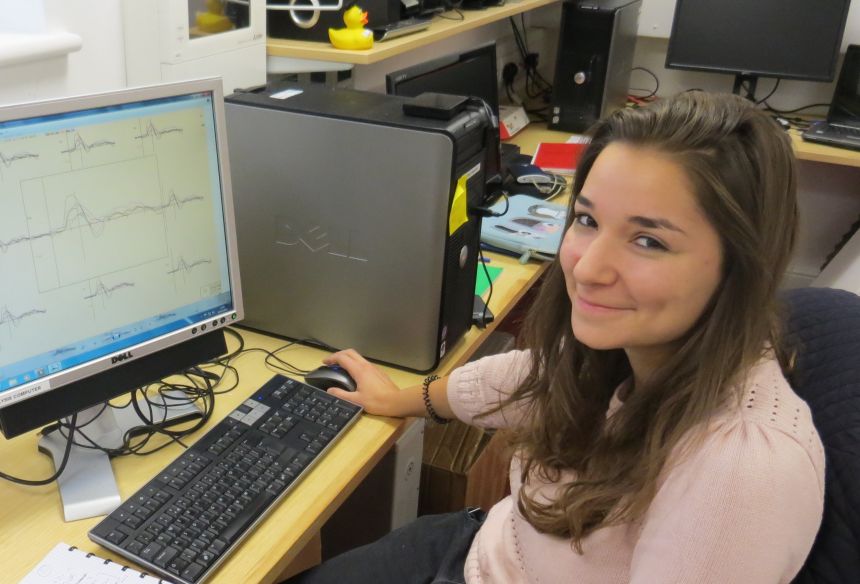

And now she’s a PhD student at Oxford’s Language and Brain Lab, using scientific techniques to see how languages make our brains tick.

“I was always really interested in linguistics, even when I didn’t know much about the academic discipline," she says. "At that point, I was really interested in learning languages.

“And I wasn’t just interested in mastering a new language. I wanted to know what was going on in our brains when we speak one.”

Swetlana is a native German speaker, and grew up in Aachen, Germany. After a childhood learning French and English, and making her own connections between the languages, Swetlana sat down in a lecture theatre at Cambridge for her very first lecture on psycholinguistics.

“I was just blown away. It was incredibly interesting,” she remembers.

Three years later, she came to Oxford to complete an MPhil at the Language and Brain Lab. Now, she’s in the midst of a PhD (or DPhil, as they are known here), working with Professor Aditi Lahiri, and her own experiences have always criss-crossed with her research interests.

Swetlana’s research looks at how native German speakers process words in the brain. This work has also made Swetlana think more about how our brains respond to second (or third or fourth or fifth) languages when we learn them.

Her research has taken her from Leipzig to Chicago to California, using the sort of equipment that we’re more likely to associate with the sciences than the humanities.

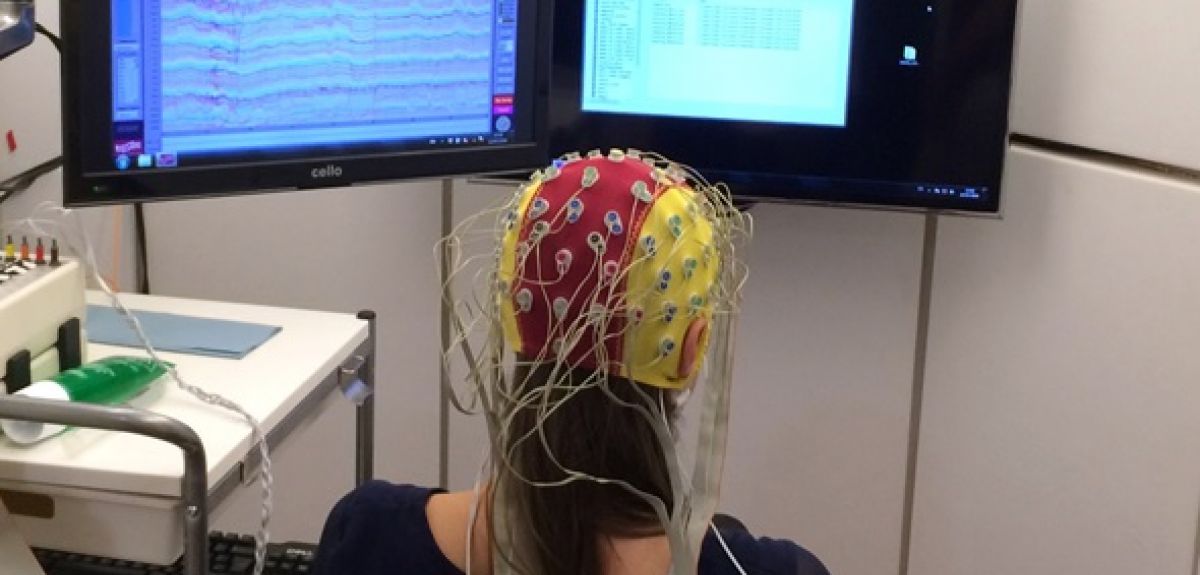

“We use fMRI scanners and an EEG system for part of the experiments,” Swetlana explains.

This means that Swetlana has spent a lot of time examining fMRI scans and carefully placing electrodes onto participants’ heads. She even had the opportunity to run experiments at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig.

“The process of collecting your data can be quite challenging, especially when you’re running experiments abroad,” she says. “But Leipzig was such an exciting opportunity. I learnt so much from collaborating and sharing ideas.”

Now back in Oxford, Swetlana is writing up her research and making the most of Oxford life, both within and outside of the Lab.

“There’s something very special about the Linguistics Faculty,” Swetlana says. “It’s a really supportive environment but also intellectually stimulating.”

And outside of work, college life offers the opportunity to see what else is going on in Oxford’s labs and libraries.

“It’s really fun to be friends with people who have interests in areas completely different to you,” she says.

This is especially interesting for Swetlana, who has thought about how her brain scans and electrodes, which some might think are out of place among the manuscripts and archives of the humanities, fits in to humanities research.

“The idea in our Faculty is to see how everything is connected,” she says. “Looking at how languages change over time, for example. I love how we contribute different approaches to the big questions.”

Another big question is how Swetlana’s research relates to her own language-learning brain.

“It’s made me think about my own languages,” she says. “Bilingualism is something we’re looking into more and more, sometimes from unexpected angles.”

After her DPhil, Swetlana hopes to carry on in research. She’s also interested in language technology, and how language-learning apps could help us learn languages more effectively - so that we, too, could learn to gossip in German or flirt in French.

“I’ve really enjoyed the past six years,” Swetlana says. “And I’m excited to keep on exploring.”

Swetlana is studying a PhD in linguistics

Swetlana is studying a PhD in linguisticsAn artist at Oxford University has won the 2017 Film London Jarman Award.

Oreet Ashery was recently appointed as Associate Professor of Contemporary Art at The Ruskin School of Art and a Fellow of Exeter College.

She has made an immediate impact, winning the prestigious award for UK-based artists working with the moving image. Her successful entry was a 12-part, web-based video series called Revisiting Genesis.

The series looks at the modern death industry and follows an artist with cystic fibrosis and a painter who has had cancer, as well as carers, friends and curators. The films contained stories of Syrian refugees and the people trying to help them, which she recorded in Thessaloniki, Greece earlier this year.

The Guardian interviewed Oreet about her work here.

'I was interested in how people work together,' Oreet told The Guardian. 'Telling stories in a darkened room. Even if no one speaks, that is a story, too.'

Anthony Gardner, Head of the Ruskin School of Art , said: 'We're thrilled that Oreet's enormous talent has been recognised with this award, given in honour of one of the UK's great film-makers to celebrate the next generation of artists using film and moving-image.

'And like Derek Jarman himself, Oreet is not only a great artist but also a great teacher and mentor, which makes her success with the Jarman Award even more fitting.'

The Ruskin School of Art has punched above its weight in the art prize categories in recent years. In the last three years alone, its tutors and alumni have won two Turner prizes (Elizabeth Price and Helen Marten), one Hepworth prize (Helen Marten) and now a Jarman Award.

The Film London Jarman Award recognises and supports the most innovative UK-based artists working with moving image, and celebrates the spirit of experimentation, imagination and innovation in the work of emerging artist filmmakers.

Launched in 2008 and inspired by visionary filmmaker Derek Jarman, the Jarman Award is unique within the industry in offering both financial assistance and the rare opportunity to produce a new moving image work.

There is an interview with Oreet Ashery in The Guardian here. You can watch Revisiting Genesis here.

Oreet Ashery

Oreet AsheryChristina Holka

Research led by Oxford University highlights the accelerating pressure on measuring, monitoring and managing water locally and globally. A new four-part framework is proposed to value water for sustainable development to guide better policy and practice.

The value of water for people, the environment, industry, agriculture and cultures has been long-recognised, not least because achieving safely-managed drinking water is essential for human life. The scale of the investment for universal and safely-managed drinking water and sanitation is vast, with estimates around $114B USD per year, for capital costs alone.

But there is an increasing need to re-think the value of water for two key reasons:

- Water is not just about sustaining life, it plays a vital role in sustainable development. Water’s value is evident in all of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals, from poverty alleviation and ending hunger, where the connection is long recognised - to sustainable cities and peace and justice, where the complex impacts of water are only now being fully appreciated.

- Water security is a growing global concern. The negative impacts of water shortages, flooding and pollution have placed water related risks among the top 5 global threats by the World Economic Forum for several years running. In 2015, Oxford-led research on water security quantified expected losses from water shortages, inadequate water supply and sanitation and flooding at approximately $500B USD annually. Last month the World Bank demonstrated the consequences of water scarcity and shocks: the cost of a drought in cities is four times greater than a flood, and a single drought in rural Africa can ignite a chain of deprivation and poverty across generations.

Recognising these trends, there is an urgent and global opportunity to re-think the value of water, with the UN/World Bank High Level Panel on Water launching a new initiative on Valuing Water earlier this year. The growing consensus is that valuing water goes beyond monetary value or price. In order to better direct future policies and investment we need to see valuing water as a governance challenge.

Published in Science, the study was conducted by an international team (led by Oxford University) and charts a new framework to value water for the Sustainable Development Goals. Putting a monetary value on water and capturing the cultural benefits of water are only one step towards this objective. They suggest that valuing and managing water requires parallel and coordinated action across four priorities: measurement, valuation, trade-offs and capable institutions for allocating and financing water.

Lead author Dustin Garrick, University of Oxford, Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, explains: ‘Our paper responds to a global call to action: the cascading negative impacts of scarcity, shocks and inadequate water services underscore the need to value water better. There may not be any silver bullets, but there are clear steps to take. We argue that valuing water is fundamentally about navigating trade-offs. The objective of our research is to show why we need to rethink the value of water, and how to go about it, by leveraging technology, science and incentives to punch through stubborn governance barriers. Valuing water requires that we value institutions.’

Co-author Richard Damania, Global Lead Economist, World Bank Water Practice said: ‘We show that water underpins development, and that we must manage it sustainably. Multiple policies will be needed for multiple goals. Current water management policies are outdated and unsuited to addressing the water related challenges of the 21st century. Without policies to allocate finite supplies of water more efficiently, control the burgeoning demand for water and reduce wastage, water stress will intensify where water is already scarce and spread to regions of the world - with impacts on economic growth and the development of water-stressed nations.’

In conclusion, co-author Erin O’ Donnell, University of Melbourne adds: ‘2017 is a watershed moment for the status of rivers. Four rivers have been granted the rights and powers of legal persons, in a series of groundbreaking legal rulings that resonated across the world. This unprecedented recognition of the cultural and environmental value of rivers in law compels us to re-examine the role of rivers in society and sustainable development, and rethink our paradigms for valuing water.’

- ‹ previous

- 82 of 248

- next ›

Teaching the World’s Future Leaders

Teaching the World’s Future Leaders  A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future

A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance

Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance

The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance  The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham

The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham  Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year

Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage