Features

This is the latest in the Artistic Licence series.

Louisa Olufsen Layne loves literature. She also loves reggae.

Growing up in Norway, she devoured Dostoyevsky and soaked up her Dad’s record collection. Now, at Oxford, Louisa is bringing her interests together.

Louisa is a fourth-year DPhil student studying English. Talking about her love for literary theory and her ear for Jamaican music, she explains how a desire to combine the two brought her to Oxford.

“I thought there was something compelling about bringing those two worlds together,” she explains.

The poet Linton Kwesi Johnson turned out to be the key. Johnson is well-known for developing dub poetry, a genre heavily influenced by reggae music.

Primarily active in the 1970s and 1980s, Johnson developed a style of poetry that crosses the boundary between poetry and performance. He also toured with punk performer John Cooper Clarke.

Louisa was fascinated by Johnson, and after studying his poetry for her master’s degree in Oslo, she knew she wasn’t finished with him.

'I liked the UK, I liked the university culture, and I met some people who had gone to Oxford,' Louisa remembers. 'They said I should consider applying here. So I did!'

Louisa has now spent the past four years working on Linton Kwesi Johnson’s poetry and making the most of what Oxford has to offer.

Coming to Oxford as an international student and a graduate was a big change for Louisa. 'When you change institutions, you start to see things quite differently,' she says. 'Oxford gave me much more of a historical interest.'

On the personal side, adjusting was a little more challenging. 'When I first came here, I didn’t know anyone, so I was quite shy,' she admits. 'The first seminars I went to, I felt quite intimidated.

'But then you get used to the environment. I started to feel more confident in this new place, and all of a sudden, people go from being strangers to becoming your friends.'

The postcolonial seminar in the English Faculty gave Louisa her first tastes of home in Oxford. “The postcolonial seminar has really been kind of like a home here,” she says.

Attending the seminar brought Louisa to a community of people working on topics ranging from black British writing to Caribbean and World literature. Inspired by the conversations taking place, Louisa decided to get involved in organisation herself. Last year, she began co-convening the Race and Resistance network at TORCH.

This proved to be an exciting move. In February, Louisa organised an event on hiphop for the network with her colleague Dr. Imaobong Umoren.

“Marcyliena Morgan, the director of the Hiphop Archive and Research Institute at Harvard, came to talk about the study of hiphop,” she says. “For me, that was one of the highlights.”

During the event, Morgan talked about how British and American scholars can research and exchange knowledge not only on hiphop, but also on British rap and grime, and other forms of contemporary culture.

'It added an interesting perspective,' Louisa says. 'Marcyliena Morgan was talking about how they’ve had hip-hop fellows, and have an archive of the best hip-hop albums. Oxford is very good at historical topics and disciplines, and should continue being so, but we also have room for contemporary culture and criticism.'

So while bringing together her love of literature and music, Louisa has made some pit stops along the way—delving into hiphop, African-American literature, and punk lyrics. It’s these opportunities to explore such diverse areas that Louisa has relished while at Oxford.

'There’s so many things going on, so if you get involved, like I did, it opens up possibilities,' she says.

This is the latest in the Artistic Licence series.

Since the first films emerged in the 1890s, in societies of all eras, sizes, and ideologies, movies have had us enraptured.

And Catriona Kelly, Professor of Russian at New College, is exploring how one Soviet film studio has contributed to this long and colourful world of cinema - both on- and off-screen.

Lenfilm, a film studio based in Leningrad, was the second-largest production company in the Soviet Union, after Mosfilm, the Moscow studio. At its height in the 1960s and early 1970s, when a cluster of young filmmakers began making adventurous new movies, it produced up to fifty films a year.

These ranged from The Amphibian Man (1962), a science fiction movie about a man with shark gills, to A Boy and a Girl (1966), a film about two young people’s holiday relationship that was banned immediately after its release.

Through archive material and oral history interviews, Professor Kelly is using Lenfilm, which was a vast film factory with over 4,000 employees, as a window onto life in the USSR.

While amphibian-like men swam around onscreen, Lenfilm employees were working collectively on the film-making process, dealing with budgets, equipment supply, and censorship. Exploring how the organisation worked gives us an unusual angle on the role of the Communist Party in the Soviet Union.

“The Party wasn’t just an ideological censor. It was the only management structure that united the whole studio, from location to wigs and makeup. When it disappeared, the studio fell apart,” Professor Kelly says.

Looking at the institutional history has also thrown up some examples of more familiar, Hollywood-esque problems, like people getting drunk in the film processing laboratories, or storming off set because the director swore at them.

But despite the occasional angry outburst, Lenfilm produced many successful films. These included crowd pleasers like the all-singing, all-dancing Wedding in Malinovka, a comedy operetta set during the Russian Civil War, but also films that were more serious or experimental in tone, such as Aleksei German’s My Friend Ivan Lapshin (1984).

“The films were often characterised by a quasi-documentary, neorealist approach to Soviet society, and some of them were quite hard-hitting,” Professor Kelly says.

One of her favourites is Gennady Shpalikov’s A Long Happy Life (1967), a love story about a man who hitches a lift on a passing coach and a woman he meets on it.

At the peak of their popularity, hit films like Amphibian Man were watched by up to 100 million people. Some, like Grigory Kozintsev’s Hamlet and King Lear, or, more surprisingly, Sergei Mikaelyan’s Bonus (1975), about workers in a Soviet factory, garnered appreciative audiences and prestigious prizes across the Soviet Union and abroad.

In the early 1970s, audience numbers began to drop, but films remained popular—and some of them still are. “TV reduced audiences in cinemas, but people also avidly watched films on TV. Indeed, they still do, and popular Soviet films are widely watched on YouTube,” Professor Kelly says.

Professor Kelly has first-hand experience of this appetite for Soviet films. Throughout her research project on Lenfilm, she has shown some of the studio’s films to audiences in Oxford, and even hosted some Lenfilm directors in the city.

“These events are popular with members of the public - they’re interested in seeing something they can’t see in a commercial cinema,” she says. So far, they’ve had visits from Konstantin Lopushansky, Vitaly Melnikov and Yuly Fait, and are planning more showings for the upcoming year, which is the centenary of the Russian Revolution.

As well as offering an insight into the history of the USSR, Professor Kelly thinks that production studios like Lenfilm have an important impact on Russia today. “Film was an enduring part of popular culture,” she says.

Curious? Watch Wedding in Malinovka for yourself here.

The fast pace of disease outbreaks and the regular emergence of new drug-resistant strains makes the development of vaccines increasingly important. Helen McShane, Professor of Vaccinology at the Nuffield Department of Medicine, explains the role of international research collaborations in the global fight against infectious diseases.

Developing new vaccines to protect against disease is a race against the clock. As scientists and clinicians around the world work to tackle outbreaks, the emergence of new drug-resistant strains makes the need for preventative vaccines all the more important.

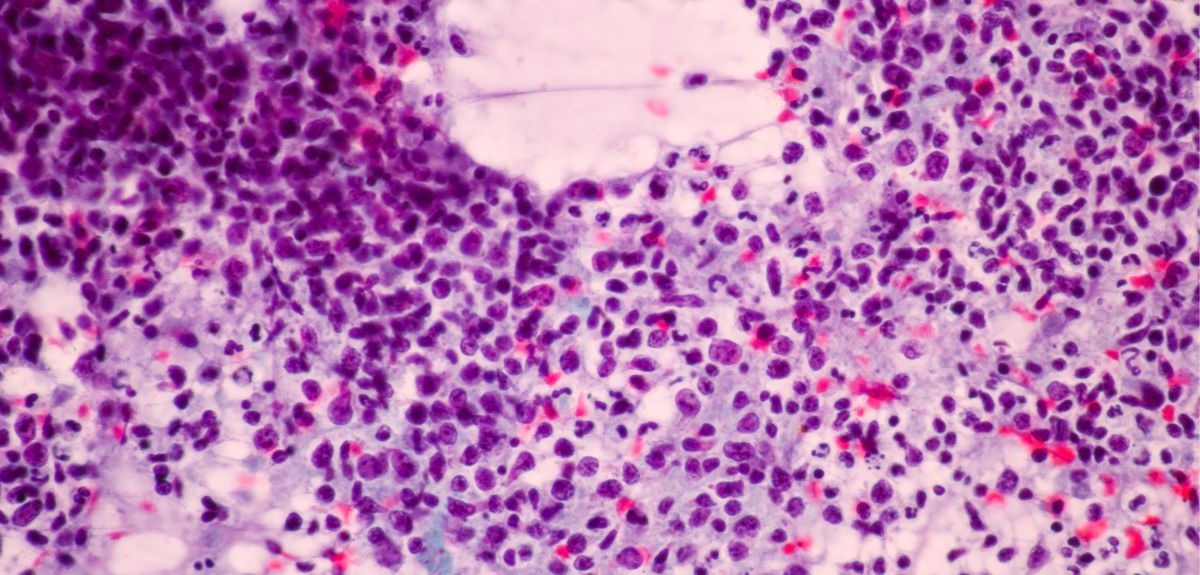

As an example, TB is currently the leading cause of death by infectious disease worldwide, ranking above HIV/AIDS. In 2016, there were an estimated 10.4 million new cases of TB worldwide and 1.6 million deaths. In the same year there were 600,000 new cases with resistance to rifampicin (RRTB), the most effective first-line drug, of which 490 000 had multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). Almost half (47%) of these cases were in India, China and the Russian Federation.

Vaccines are incredibly effective in combatting disease. Current childhood vaccines are estimated to prevent 2-3 million deaths per year worldwide, not to mention the countless lives that have been saved through the eradication of smallpox and the near eradication of polio.

However, the only current vaccine we have against TB is the BCG vaccine, which is almost a century old and only grants limited protection against the disease – especially in high-risk areas.

The World Health Organisation’s (WHO) End TB Strategy, adopted by all WHO member states in 2014, set a target of decreasing TB incidence by 80% and reducing TB deaths by 90% by 2030.

There is a stark gap between where we are and where we need to be, but working together significantly improves our chances of finding new vaccines and treatments. The ace up our sleeve in this ongoing battle is that there are thousands of researchers across the globe tackling the same problems from different angles simultaneously.

Our own team in Oxford, in partnership with the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, was recently awarded a £1.7million MRC/BBSRC GCRF grant to set up and lead an international network of researchers working towards vaccine development for TB, leishmaniasis, melioidosis and leprosy – called VALIDATE (vaccine development for complex intracellular neglected pathogens). The VALIDATE Network aims to accelerate this vaccine development as well as to encourage Continuing Professional Development and career progression amongst its members, particularly early career researchers and researchers from LMICs. We currently have 73 members from 37 institutes in 15 countries, but we are looking to grow the network considerably.

Creating an interactive community of researchers who are forming new cross-pathogen, cross-continent, cross-species and cross-discipline collaborations, generating new ideas, taking advantage of synergies and quickly disseminating lessons learned across the network, will help us to make significant progress towards vaccines against the focus pathogens.

This is just one of a number of international collaborations we’re involved with. Through the Medical Research Council’s Vaccine Networks researchers here at Oxford are linked to teams worldwide tackling diseases as broad as malaria, ebola, zika and plague. The UK Government Department of Health together with the MRC and BBSRC launched the UK Vaccine Network as a direct response to the recent ebola and zika outbreaks, which threatened to spread far more widely than they eventually did.

The development and manufacture of vaccines is one of the more complex and slow processes in biopharmaceuticals.

However, multiple vaccine development teams sharing their findings from clinical trials can speed the process up immensely. The UK Vaccine Network has developed a process map to support researchers through the key stages in vaccine development and to help them to identify where bottlenecks could potentially delay progress. Through use of this map, it is hoped that researchers can identify any potential delays well in advance and make plans to overcome them. This should help expedite and streamline vital vaccine development, ultimately enabling more lives to be saved.

Professor Helen McShane is Director of VALIDATE, and Dr Helen Fletcher at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine is Co-Director.

Arts graduates - do you have that one friend who always criticises your degree? Well, we have some good news - a new report released by the British Academy has evidence to back you up.

The Academy has published a report into the skills that the 1.25 million students who study arts, humanities and social science (AHSS) develop through their degrees.

Researchers found that the skills in demand from employers were the same as those developed by studying AHSS: namely, communication and collaboration, research and analysis, and independence and adaptability.

Oxford set the agenda for this kind of research in 2013, when it commissioned a report into the destinations of Oxford graduates of English, History, Philosophy, Classics and Modern Languages.

After tracking the employment history of 11,000 graduates, it found that 16-20% were employed in key economic growth sectors of finance, media, legal services and management by the end of the period. Over the period, the number of graduates employed in these sectors rose substantially.

The British Academy’s report takes this further and pinpoints why it is that AHSS graduates have such success in these fields. And Oxford’s Head of Humanities, Professor Karen O’Brien, is delighted.

"We warmly welcome the report's articulation of the higher level skills and competencies which arts, humanities and social sciences (AHSS) bring to the national workplace,” she says.

“The report demonstrates the valuable ability of AHSS graduates to evaluate ambiguous information and to seek nuanced solutions in contexts of social and cultural complexity.

"At a time when many jobs are likely to be lost through automation, the communicative and analytical skills imparted by AHSS degrees may become more relevant than ever."

An Oxford DPhil candidate has won the student award in the British Ecological Society Photographic Competition for the second year in a row.

Leejiah Dorward, a conservation researcher in the University's Department of Zoology, won the overall student prize for his stunning image of a flap-necked chameleon, taken in Tanzania and titled 'I see you'.

Leejiah also won category awards for three of his other photographs.

'Venomous Vine' - Leejiah's winning picture in the Dynamic Ecosystems category

'Venomous Vine' - Leejiah's winning picture in the Dynamic Ecosystems category 'Home sweet home' - Leejiah's winning picture in the Ecology and Society category

'Home sweet home' - Leejiah's winning picture in the Ecology and Society category 'Shivering sylph' - Leejiah's winning picture in the Individuals and Populations category

'Shivering sylph' - Leejiah's winning picture in the Individuals and Populations category 'I see you' - Leejiah's overall winning picture

'I see you' - Leejiah's overall winning picture- ‹ previous

- 81 of 248

- next ›

Teaching the World’s Future Leaders

Teaching the World’s Future Leaders  A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future

A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance

Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance

The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance  The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham

The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham  Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year

Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage