Features

TORCH (The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities) will welcome Professor Joy Owen as its Global South-Mellon Visiting Professor 2018-2019.

Professor Owen is Head of Department and Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of the Free State, Bloemfontein in South Africa. Prior to her employment at the UFS, she was Head of Department (Anthropology) and Deputy Dean of Humanities at Rhodes University, Grahamstown.

Professor Owen's research currently explores the social networks of South African transnational migrants who have migrated to Germany, Australia and New Zealand. In the process of doing so she is considering the importance of social and cultural capitals to the ‘successful’ migration of South Africans to these three countries. Her sojourn in Germany in 2016 gave her first-hand experience of transnational migration and the difficulties inherent in ‘connecting’ with those who are nationally different. Over the next few years, she will explore these three sites more specifically through direct participation and observation.

During the period of her visiting fellowship at Oxford, Professor Owen plans to focus on two strands of research that are related to each other. The first originates within her doctoral research on Congolese transmigrants in Cape Town, South Africa. The second arises from her interest in the South African ‘diaspora’ present in New Zealand and Australia. Her knowledge and expertise are a timely contribution to work that is ongoing to make curricula and conversations at Oxford more inclusive.

Professor Owen said: ‘I am pleased to be joining TORCH and working with both Wale Adebanwi and the African Studies Centre at this exciting time, and for my research to be so warmly received by colleagues in the humanities at Oxford. I am looking forward to teaching and engaging with students and sharing ideas and perspectives on research, racialised identities and migration.’

Professor Wale Adebanwi, Director of the African Studies Centre and Rhodes Professor of Race Relations at the University of Oxford, said: ‘Joy is a wonderful addition to TORCH and the Faculty of Anthropology. Her research has been influential and pioneering and throws light on important topics such as transnational migrations. Joy will mentor students, lead open events in collaboration with the African Studies Centre and the Africa-Oxford Initiative, and contribute to Oxford in a number of other ways while she is with us.’

Professor Owen will be based at TORCH and St Anne's College during Trinity Term. Her works include the monograph Congolese Social Networks: Living on the Margins in Muizenberg, Cape Town (Lexington Books: 2015), and articles such as “Xenophilia in Cape Town, South Africa: New Potentials for Race Relations?” in City and Society Vol 28.3 (2016), “Transnationalism as Process, Diaspora as Condition” in Journal of Social Development in Africa Vol 30.1 (2015). Her most recent publications are “Humanising the Congolese Other: Love, Research and Reflexivity in Muizenberg, South Africa”, published in R. Boswell and F. Nyamnjoh (eds.), Postocolonial South-African Anthropologies, in 2017, and “Sade – By your Side” published in Suomen Antropologi: Journal of the Finnish Anthropological Society Vol 43.2 (2018).

The TORCH Global South Visiting Professorships Programme is designed to bring world-leading figures to the University of Oxford for at least one term and to be included in the teaching and research environment, hosted by leading academics in the humanities. Funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the programme is a collaboration between the faculties of Oxford's Humanities Division and the colleges of the University of Oxford.

By Dr Cayenna Ponchione-Bailey, junior research fellow at Somerville College; college lecturer in music at St Catherine’s College; postdoctoral researcher on the Transforming 19th-Century Historically Informed Practice project; associate conductor, Orchestra of St John’s.

In Afghanistan, young women making music in public is a bold political act. To been seen, to be heard — particularly through musical expression — is radical for women living in Afghanistan today. Yet there is a group of young women defying all the odds to assert their right to make music — they form Ensemble Zohra, the first all-female orchestra in Afghanistan. Through their courage they are pushing back 40 years of repression and inspiring a whole new generation of young men and women. In March, these young women will be in residence in Oxford for a week in a historic visit which promises to be the beginning of an exciting and enduring relationship between the Afghanistan National Institute of Music and the city of Oxford.

Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the rise of the Taliban, a rich musical culture was silenced for decades with women’s access to musical participation completely forbidden. Despite the political and security changes after 2001, there are still large portions of the Afghan population that do not approve of music-making, especially for women and even more particularly in mixed groups of men and women. Pushing these social boundaries, Dr Ahmad Sarmast founded the Afghanistan National Institute of Music (ANIM) in 2010. ANIM is co-educational and teaches the national curriculum alongside a full music programme including history, theory and practical performance on both traditional Afghan and Western classical instruments.

Based in Kabul, ANIM is dedicated to providing access to music education across all sectors of Afghan society, ensuring that street children and orphans have as much access as more middle-class families. Students from the outlying provinces often move to Kabul to live in orphanages as much to be in proximity as to be safe from family members who disapprove of their musical activities.

The school is a ‘safe space’ for the girls (from age a very young age through to their early 20s) where they are equal to their male peers in all ways. While girls participate in all aspects of musical performance alongside the boys, in 2015, Meena, a young trumpet player approached Dr Sarmast because she wanted the girls to have their own group, to take ownership of their performance and repertoire and form an all-female orchestra—Ensemble Zohra.

I first became aware of Ensemble Zohra through an online news article about Negin Khpalwak, the first Afghan female orchestra conductor, with whom I felt immediate sympathies as my own youth was spent trying to become an orchestra conductor in the middle of Alaska. Negin had to move from her traditional Pashtun community in rural Afghanistan to Kabul when her uncle threatened to kill her if she pursued her musical ambitions. Let’s not pretend for an instant that growing up in Alaska and living in an orphanage in Kabul are the same things, but what they do have in common is a remoteness from the rich orchestral landscape that is taken for granted in the UK and throughout much of Europe. Throughout the rocky and unpredictable journey that is any conducting career, there is no replacement for the multitude of experiences and knowledge gained by having access to such a wide range of orchestral practices and musicians. I was instantly inspired by her story and began to lobby my orchestra to bring her to the UK for a two-week professional development programme. Very quickly the conversation turned towards bringing the entire group here and thus began a life-changing journey…

It didn’t feel right to invite the young women here without going to meet them first, so within a few months I had booked a flight to Kabul and spent a week visiting the music school. I was fortunate to have local hosts who helped me navigate the city safely, but even in Kabul which is under the control of the Afghan Government, I only entered buildings with armed guards and frequently underwent pat-downs and bag searches, even to enter malls or restaurants. Students are not able to take instruments home with them to practice as the risk of violence and theft is too high. In 2014 a public performance was attacked by a suicide bomber where one audience member died and the school’s director nearly lost his life. Fortunately, no students were killed in the blast. A week after I left, a school in another district of Kabul was attacked killing 48 pupils and teachers. But that is the reality for those pushing forward on the ground in Afghanistan.

As an orchestra conductor and academic with a specialism in the social psychology of orchestral music-making, I found the situation at the school fascinating. Unlike El Sistema’s project of cultivating primarily Western orchestral practices, all of the orchestras at the school combine traditional Afghan and Western classical instruments, performing arrangements of traditional and popular Afghan and Western classical music. In doing so the practice re-signifies orchestral music-making, creating a uniquely Afghan sound and musical culture. Naturally, it is not as simple as that, and coming in from the outside I immediately saw tensions between a variety of potential objectives. One such tension lies in how one balances the development of individual musicians, such as those with orchestral aspirations and potential on an international stage, with the desire to promote an authentically Afghan musical practice when there is yet to be a professional (or even amateur, for that matter) orchestral music scene in Afghanistan.

Becoming a musician in Afghanistan is not straightforward — especially if you are female. There are no orchestras to audition for or regular chamber music series in concert halls, nor are there acres of budding pianists whose parents will bring them to your studio for weekly lessons. Public performances are risky. A life in music for these young people will require an incredible amount of innovation, creativity, risk-taking and perseverance. They will become cultural leaders in the process.

Inviting them to Oxford for a week-long residency is one way that we can support this journey, and in exchange we will be opened to a whole new way to be an orchestra, new musical landscapes and new friendships. In residence at Somerville College, the young women will be embedded in an environment that has spearheaded the education and empowerment of women for over a hundred years. Ensemble Zohra will rehearse and perform with Oxford University students, young musicians from the Oxfordshire County Music Service, and the professional musicians of the Orchestra of St John’s.

Ensemble Zohra will be giving public performances at the British Museum on 15 March; Harrow Arts Centre on 16 March; and Sheldonian Theatre on 17 March. The traditional section of the orchestra will also be performing on a special programme led by musicologists Professor John Bailey (Goldsmiths) and Veronica Doubleday at the Holywell Music Room on 13 March. A panel discussion on women’s education in Afghanistan will take place at Somerville College on 14 March. More information about these events and information on how to buy tickets can be found at www.osj.org.uk.

Babel: Adventures in Translation, a new exhibition at the Bodleian Libraries opening on 15 February, explores the power of translation from the ancient myth of the Tower of Babel to the challenges of modern-day multicultural Britain in light of Brexit. Featuring a stunning range of objects from the Libraries’ collections, the exhibition shows how ideas and stories have travelled across time and territory, language and medium.

Babel explodes the notion that translation is merely about word-for-word rendering into another language, or that it is obsolete in the era of global English and Google Translate. It shows how translation is an act of creation and interpretation, and has been part of our daily lives since time began.

Katrin Kohl, Professor of German Literature at the University of Oxford, and co-curator of the exhibition said: “Babel explores the tension between the age-old quest for a universal language, like Latin, Esperanto or global English today, and the fact that communities continue to nurture and retain their own languages and dialects as part of their cultural identity. The exhibition illuminates how translation builds bridges between languages and how the borderlands between languages can be fertile ground for resistance, comedy and creativity.”

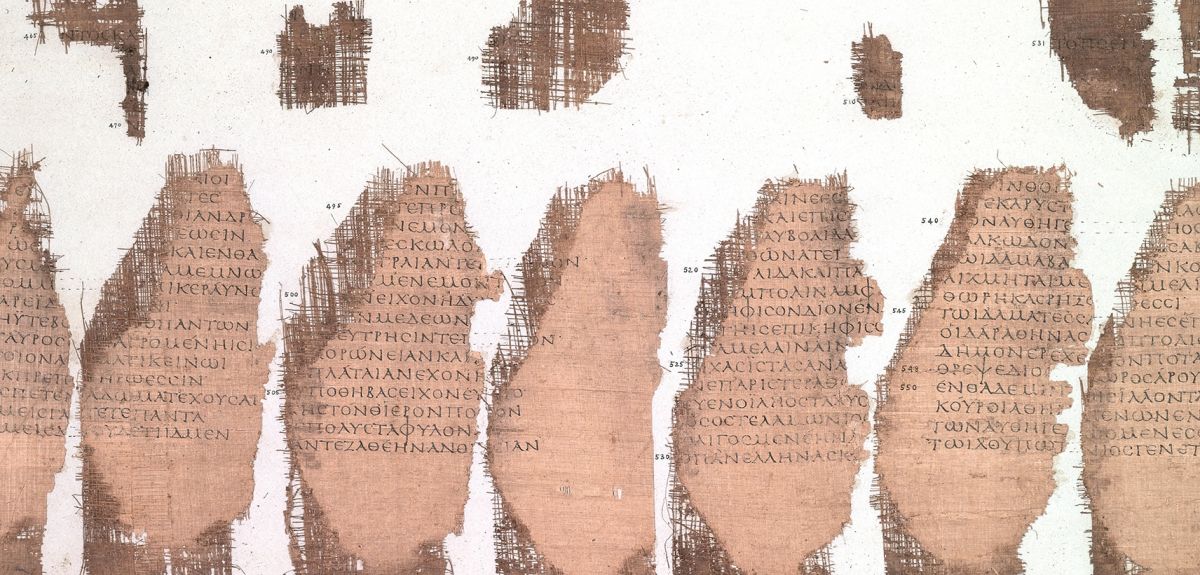

Ancient treasures – such as a second-century papyrus roll of Homer’s Iliad, a mathematical textbook from ninth-century Byzantium, and a beautiful illuminated manuscript of Aesop’s Fables – will be shown alongside contemporary objects such as signage, branding and leaflets that draw on multiple languages to speak to a global audience. Exploring fantasy and fairy tales, the translation of divine texts and the endeavour to create a universal scientific language, the exhibition will appeal to adults and young people alike and anyone interested in language, science, religion and the power of stories.

Exploring themes of multiculturalism and identity, the exhibition considers issues that are more relevant than ever as Britain approaches Brexit. Iconic ancient texts and modern ephemera remind us that the British Isles always have been, and still are, multilingual. Looking ahead – to the very distant future – the exhibition also considers the thorny problem of how to mark the sites where nuclear waste is buried so that the warning will still be intelligible many thousands of years from now.

Highlights of the exhibition include:

- The spectacular Codex Mendoza, a unique manuscript from around 1541 which uses picture writing alongside the Mexica language, Nahuatl and Spanish in order to brief Spanish imperial rulers on their new lands in Mexico

- A 3,500-year-old bowl inscribed with a mysterious script that still resists deciphering

- An unpublished notebook kept by JRR Tolkien revealing how he created his own ‘Private Scout Code’ at the age of 17 while studying Esperanto. This is the first known example of him inventing an alphabet, and foreshadows his fictional Elvish alphabet and languages

- Matisse’s illustrations from a rare edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses in which the artist sketched scenes from Homer’s Odyssey rather than Joyce’s novel, which he had not read

- Different versions of Cinderella – by Charles Perrault, the Grimm brothers, Shirley Hughes, and in pantomime and film – showing how stories have been transferred across cultures, resulting in new interpretations across time, space and different media

- Iconic medieval texts that speak of Britain’s rich linguistic heritage, including The Red Book of Hergest, one of the four Ancient Books of Wales, and The Annals of Inisfallen, which chronicles the medieval history of Ireland

- An experimental 1950s computer programme designed by Christopher Strachey to generate convincing love letters

- Dans le Chip Shop, a humorous sketch from Miles Kingston’s book Let’s Parler Franglais!, which mixes English and school-child French to comic effect and celebrates its 40th anniversary this year

- A mathematical textbook from 1557, The Whetstone of Witte, containing the first recorded use of the equals sign

Richard Ovenden, Bodley’s Librarian, said: “Babel is a fascinating exhibition that shows us how translation has shaped our modern lives – in religion and science, politics and literature, food and health. The Bodleian Libraries is an incredible treasure-house of great works that have grown out of the transfer processes between languages, and the exhibition showcases some of these extraordinary items with great effect, changing the way we think about translation today.”

The exhibition was curated by the following co-curators at the University of Oxford alongside Professor Kohl: Dennis Duncan, a writer and translator, and Visiting Fellow at St Peter’s College; Stephen Harrison, Professor of Latin Literature and Fellow and Tutor in Classics at Corpus Christi College; and Matthew Reynolds, Professor of English and Comparative Criticism and Fellow and Tutor in English at St Anne’s College.

The exhibition team is collaborating with Creative Multilingualism, a four-year research programme led by Professor Kohl, which is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council as part of the Open World Research Initiative. The project is investigating the interconnection between linguistic diversity and creativity, with Professor Reynolds leading a research strand on Prismatic Translation.

In the Bodleian’s Babel exhibition, visitors will be able to explore digital interactives including the opportunity to listen to texts from the exhibition read in their original languages, ranging from Tibetan and Sanskrit to Italian and German.

Babel will be accompanied by an engaging programme of free talks and events at the Bodleian’s Weston Library, including a Library Late event on 8 March, which will be an interactive evening celebrating languages and cultures. For more information visit www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/whatson.

An accompanying publication to the exhibition, Babel: Adventures in Translation, will be released by Bodleian Library Publishing on 15 February, and is available for pre-order from www.bodleianshop.co.uk. The book is authored by Dennis Duncan, Stephen Harrison, Katrin Kohl and Matthew Reynolds.

After The Favourite, starring Olivia Colman as Queen Anne, cleaned up at the Baftas last night, Professor Paulina Kewes of Oxford's Faculty of English and Jesus College talked to Arts Blog about why the Stuart dynasty remains so fascinating. Professor Kewes' new book, Stuart Succession Literature: Moments and Transformations, was launched last month, published by OUP.

Why is the Stuart period of such enduring interest?

The Stuart era gave shape to modern Britain. Britain’s political and constitutional foundations were forged between the accession of the first Stuart monarch of England, James I, in 1603 and the death of the last one, Queen Anne, in 1714. The Anglo-Scottish union, the emergence of political parties, and the law which still regulates the order of royal succession today were all products of this period, which also witnessed the only years of republican rule in the nation’s history. By its end, Britain stood as an international force in the world of trade and empire: it was on the way to becoming a superpower, while social and economic change at home had transformed the lives of citizens. The Stuart Age also saw extraordinary cultural achievement: from Shakespeare to Milton, the playhouse to the opera. The ubiquity of print democratised information and culture alike.

The transition from the Tudors to the Stuarts in 1603, when the Scottish king James VI ascended the English throne as James I, is especially fascinating. Few realise just how fraught the preceding years had been, and how fiercely contested was the Stuart claim. After all, Elizabeth had condemned James’s Catholic mother, Mary Stuart, to the block. Josie Rourke’s recent film Mary Queen of Scots concludes with the shadowy image of King James. How and why did it come to pass that he managed to ascend the English throne unopposed despite the historic rivalry between England and Scotland, and, more to the point, despite the execution of his mother by the English? What did James’s new subjects make of their Scottish king whom virtually none of them had ever seen before, and how did he work to reassure them? Printing presses in London churned out poems of praise, genealogies, sermons, succession tracts, addresses and ballads welcoming the new monarch and counselling him on how to rule. There were numerous engraved likenesses of James. Enterprising publishers hastily issued editions of his own prolific writings on monarchy and governance, religion, poetry and many other topics. For how else would his subjects get to know him?

The first Stuart succession in 1603 appeared to promise dynastic continuity: after all, James arrived in his new capital with an heir and two spares. Yet the Stuarts’ rule came to an end a little over a century later, on the death of James’s great grand-daughter, Queen Anne. Yorgos Lanthimos’ recent award-winning film The Favourite, starring Olivia Colman, may take considerable liberties with the historical record. But it nonetheless gives an imaginative insight into Anne’s queenship. Here is a monarch who, hailed as the new Elizabeth on her accession in 1702, takes the country to victories abroad. Both queens triumphed over Catholic powers: Elizabeth over the Spanish Armada, Anne over France. Yet, also like Elizabeth, Anne left no heir, though not for lack of trying. Following numerous miscarriages, stillbirths, and the death of her young son the Duke of Gloucester, Anne knew that another dynasty would rule after her: the 1701 Act of Settlement, still in force today, excluded Catholics from claiming the crown – and the only Stuarts left at that point were Catholic. Just as the Scottish Stuarts had followed Elizabeth, so the German Hanoverians came after Anne. Neither transition was expected to go smoothly. And yet, both happened without major incident. But the end of the Stuart line spelled the end of royal power: after 1714, sovereignty lay with Parliament, not the monarch.

How did your new book on Stuart succession literature come about?

The volume was inspired by a simple question: what was the public response to regime change in the Stuart era? And, since print publications and material objects such as coins and medals provide the amplest and most readily accessible record of such responses, we decided to commission essays scrutinising them from a variety of disciplinary perspectives.

This was a novel undertaking in several respects. First, because of our broad definition of Stuart succession literature: instead of confining ourselves to strictly literary works such as poems and plays, we decided to look at all sorts of printed matter: sermons, genealogies, ballads, polemical tracts, parliamentary speeches, newsbooks, libels; indeed, in order to get a better sense of the sheer volume of relevant materials, we compiled a database of succession writings printed within two years of each regime change occurring between the first and last Stuart accessions. Second, because of our extensive chronological span: scholars have traditionally focused either on the early or the late Stuart era or else on the revolutionary 1640s and 50s; we decided to trace continuity and change over the ‘Long Seventeenth Century’, from 1603 until 1714. Third, because the volume combines this diachronic approach with a synchronic one, with several chapters examining the public reaction to particular political transitions, for instance the accession of James I, or the installation of Oliver Cromwell as Lord Protector, or the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660. This double perspective underpins the structure of the book, which consists of two parts, ‘Moments’ and ‘Transformations’.

'Part I: Moments' explores how imaginative writers, divines and polemicists responded to successive regime changes. Here, alongside poems and sermons by major authors such as Daniel, Jonson and Donne, we encounter previously neglected genres (libellous pamphlet, prose romance) and viewpoints, for instance those of various religious groups or foreign commentators. Individual chapters consider, respectively: the poems which greeted the arrival of the first Stuart king, James I; the scandalous pamphlets surrounding James’s alleged poisoning which overshadowed the succession of his son, Charles I; the ambiguous and ambivalent print reception of the two Protectoral accessions; the ostensibly celebratory writings welcoming Charles II upon his return from prolonged Continental exile in mostly Catholic countries which voiced sharp anxieties about his religion; the Dutch print campaign centring on Charles’s Catholic brother James II; the complex imaginative justifications of the Revolution of 1688-9; and the extraordinary outpouring of print upon the accession of the last Stuart monarch, Queen Anne. It may come as a surprise to many to learn that one could buy a ticket to Westminster Abbey to watch the coronation of James II and his wife Mary of Modena in 1685, or of Queen Anne in 1702. Or that Isaac Newton designed Anne’s coronation medal, smuggling a subtle political message through its iconography.

'Part II: Transformations' deals with changing genres of succession literature (political tracts, royal panegyrics, sermons, prose addresses) and iconography of material forms (medals, coins, triumphant arches erected for coronation entries). The upshot is a signal revision of how those genres and forms were previously understood. For instance, we find that an explosive tract by an Elizabethan Jesuit was repeatedly appropriated by republican and Whig enemies of the Stuarts; that accession panegyrics, especially those aimed at monarchs arriving from elsewhere – James I, Charles II, and William II and Mary II – showed considerable reservations about royal authority; that accession sermons, including that by John Donne, spoke to the anxieties of a nation in transition; that the universities of Cambridge and Oxford issued highly charged volumes of poetry commemorating the deceased ruler and welcoming his or her successor; that Stuart coronations in Scotland, notably Charles I’s in 1633 and Charles II’s in 1651, bred intense anxiety in England; and that royal entries into the City of London, accompanied by elaborate pageantry and vividly described and illustrated in print, provided complex and multifaceted opportunities for exchange between the new monarch and his subjects. (The male pronoun is correct: neither Queen Mary II nor Queen Anne had a ceremonial entry into the capital.)

Overall, Stuart literature and culture emerge from our book as far more diverse, dynamic and engaged with both individual dynastic transitions and longer-term political transformations than has been recognised.

What are some of the most notable works of literature inspired by Stuart successions, and what kinds of features characterise these works?

Stuart successions inspired some of the finest literary works in English. It is often forgotten that Shakespeare was a Stuart author for much of his writing career. While several of his plays composed after the Jacobean succession subtly responded to that event offering complex meditations on kingship and the relations between rulers and ruled, it is Macbeth and King Lear – both in 1606 – that most explicitly address the proprieties of royal succession and the issue of Anglo-Scottish union. Both tragedies drew on remote, often mythic history to tackle concerns about the scope of royal power or the relative stature of the two nations; yet they did so in a way that precludes simple reading of them as tributes to the nascent Stuart monarchy. John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), published several years after the Restoration, which he had passionately opposed, was an imaginative response to it, even if Milton transposed his political preoccupations on to a cosmic level and, like Shakespeare, avoided making them transparent.

Other canonical authors – as well as a host of lesser lights – produced diverse imaginative and polemical works touching upon one or more Stuart or Protectoral successions. Ben Jonson extolled James I in his elegant panegyric which implicitly criticised Elizabeth pleading for a more tolerant attitude to Catholic dissent; Jonson also contributed to the City’s spectacular ceremonial welcome of the new king. John Donne preached a complex, allusive sermon on the accession of Charles I. Both John Dryden and Andrew Marvell commemorated the death of Oliver Cromwell, Dryden then going on to eulogise the freshly restored Charles II and soon winning the position of Poet Laureate and Historiographer Royal. Aphra Behn, the first professional female playwright, made crystal clear her Tory sympathies in a poem marking the coronation of James II and another celebrating the birth of his son, the Prince of Wales.

Far from being mere ephemeral pieces, such writings demonstrate the challenges of public political engagement. Our book brings to the fore the sophistication and variety of tone, style and expression with which their authors sought to influence both the ruler and the increasingly polarised nation. Whenever the transition to a new monarch occurs in Britain, it will generate an immediate multimedia response both in Britain and globally. The newspaper articles, television and radio programmes, images, films and YouTube videos that will accompany a change of monarch in the 21st century are the modern equivalents of the early modern succession literature examined in this book.

As well as editing the volume, you’ve contributed one of the book’s chapters...

My essay explores the shocking afterlife of a polemical tract by an Elizabethan Jesuit. Printed abroad in 1595 and swiftly smuggled into the country, Robert Persons’ A Conference about the Next Succession to the Crowne of England sought to derail the accession of the Protestant James Stuart. Its argument was deeply subversive. Feigning impartiality and lack of religious bias, the Jesuit made a case for the subjects’ right to resist an unsatisfactory ruler and exclude even the most legitimate successor. He advocated elective monarchy which gave the right of choice to the people. While Persons failed to avert the Jacobean succession, his tract proved immensely attractive to later opponents of the Stuarts. Several of them owned copies of the original edition; there were also surreptitious adaptations and a complete reprint in 1681: John Locke, among others, had it in his library. Both the Commonwealth-men who overthrew the monarchy and executed Charles I and the Whigs who toppled his Catholic son James II are shown to have drawn liberally on Persons’s 'Conference'. It is no exaggeration to say that the ideological underpinnings of the ‘Glorious’ Revolution can be traced back to this scandalous Catholic text.

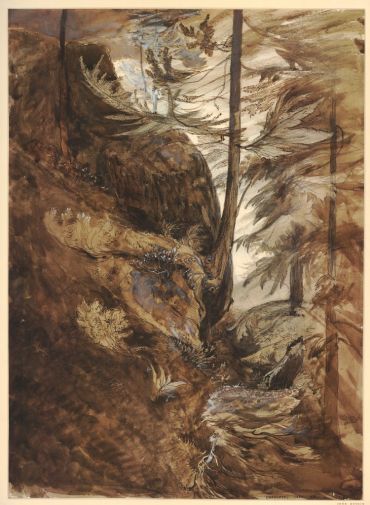

Professor Sally Shuttleworth, of Oxford's English faculty and St Anne's College, writes for Arts Blog about John Ruskin's role as an environmental campaigner. The Victorian art teacher and social reformer, who had strong views on the environmental impact of industrialisation, is the subject of a conference held in Oxford on Friday (8 February), the bicentenary of his birth.

In 1870, the historian J. R. Green, who had been exiled to the south of France for his health, wrote to a friend about startling events in Oxford:

I hear odd news from Oxford about Ruskin and his lectures. The last was attended by more than 1000 people, and he electrified the Dons by telling them that a chalk-stream did more for the education of the people than their prim “national school with its well-taught doctrine of Baptism and gabbled Catechism.” Also “that God was in the poorest man’s cottage, and that it was advisable He should be well housed.” I think we were ten years too soon for the fun!

Green’s glee at this ‘electrification’ of the Dons is palpable. The lectures to which he refers were John Ruskin’s, ‘Lectures on Art’ delivered in February and March 1870, by Ruskin in his role as the first Slade Professor of Fine Art. As Green’s summary highlights, the study and practice of art, for Ruskin, could never be separated from care for the natural environment, or concern for the material conditions of the poor. Ruskin raged against the ugliness, pollution and appalling living conditions created by industrialisation, and his argument that cities should have a ‘belt of beautiful garden and orchard round the walls’ so that ‘from any part of the city perfectly fresh air and grass and sight of far horizon might be reachable in a few minutes’ walk’ influenced the Garden Cities movement in the twentieth century, and the establishment of the principles of the Green Belt, which are under such pressure at present.

Ruskin is often treated as a lone prophetic voice, but in the ERC project I run, ‘Diseases of Modern Life: Nineteenth-Century Perspectives’, we are uncovering a hidden history of environmental campaigning, to be found in the neglected records of sanitary reformers. The ‘diseases’ we look at are those of both body and mind produced by the pressures of modernity: stress, overwork, and information overload, but also ‘diseases of impure air’, and all the problems created for health by smoke pollution and insanitary living conditions. Ruskin, together with his friend Henry Acland, who was Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford, form part of this picture, as do all the local ‘citizen scientists’, patiently taking daily readings of sunlight hours for years on end in order to show the effects of smoke pollution, or the vicar who encouraged all his parishioners to acquire gauges so that they could measure air quality.

Ruskin, it has to be said, had a love-hate relationship with science: he quarrelled violently with John Tyndall over glaciers, and had contempt for Darwin’s materialism, but the close scrutiny of the natural world, upon which all his work was based, had much in common with the practices of science. To celebrate the bicentenary of his birth, we will be holding a conference on Friday 8 February at the Oxford Museum of Natural History (in partnership with the University of Birmingham Centre for Nineteenth-Century Studies), on ‘Ruskin, Science and the Environment’, to be followed at 6pm by a public lecture on ‘Ruskin’s Trees’ by Professor Fiona Stafford, author of The Long, Long Life of Trees. It is fitting that the conference is to be held in the Museum since it was built in the 1850s on principles drawn in part from Ruskin’s writings on nature and architecture, with Ruskin himself taking an active role in its design and decoration, as a tour by Professor John Holmes tour will highlight. The conference will be accompanied by an exhibition giving a rare opportunity to see designs for the museum by Ruskin and others, including the Pre-Raphaelite artists Thomas Woolner, Alexander Munro and John Hungerford Pollen.

To book for the conference click here, and here for the 6pm public lecture. Further information about both events can be found on the project website.

- ‹ previous

- 56 of 249

- next ›

Africa’s change-makers: meet the Mastercard Foundation Scholars with big ambitions for the future

Africa’s change-makers: meet the Mastercard Foundation Scholars with big ambitions for the future A green fuels breakthrough: bio-engineering bacteria to become ‘hydrogen nanoreactors’

A green fuels breakthrough: bio-engineering bacteria to become ‘hydrogen nanoreactors’ Oxford's student voices at COP29

Oxford's student voices at COP29 Teaching the World’s Future Leaders

Teaching the World’s Future Leaders  A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future

A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance

Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance

The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance  The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham

The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham  Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year

Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year