Image credit: Shutterstock

John Ruskin, environmental campaigner

Professor Sally Shuttleworth, of Oxford's English faculty and St Anne's College, writes for Arts Blog about John Ruskin's role as an environmental campaigner. The Victorian art teacher and social reformer, who had strong views on the environmental impact of industrialisation, is the subject of a conference held in Oxford on Friday (8 February), the bicentenary of his birth.

In 1870, the historian J. R. Green, who had been exiled to the south of France for his health, wrote to a friend about startling events in Oxford:

I hear odd news from Oxford about Ruskin and his lectures. The last was attended by more than 1000 people, and he electrified the Dons by telling them that a chalk-stream did more for the education of the people than their prim “national school with its well-taught doctrine of Baptism and gabbled Catechism.” Also “that God was in the poorest man’s cottage, and that it was advisable He should be well housed.” I think we were ten years too soon for the fun!

Green’s glee at this ‘electrification’ of the Dons is palpable. The lectures to which he refers were John Ruskin’s, ‘Lectures on Art’ delivered in February and March 1870, by Ruskin in his role as the first Slade Professor of Fine Art. As Green’s summary highlights, the study and practice of art, for Ruskin, could never be separated from care for the natural environment, or concern for the material conditions of the poor. Ruskin raged against the ugliness, pollution and appalling living conditions created by industrialisation, and his argument that cities should have a ‘belt of beautiful garden and orchard round the walls’ so that ‘from any part of the city perfectly fresh air and grass and sight of far horizon might be reachable in a few minutes’ walk’ influenced the Garden Cities movement in the twentieth century, and the establishment of the principles of the Green Belt, which are under such pressure at present.

Ruskin is often treated as a lone prophetic voice, but in the ERC project I run, ‘Diseases of Modern Life: Nineteenth-Century Perspectives’, we are uncovering a hidden history of environmental campaigning, to be found in the neglected records of sanitary reformers. The ‘diseases’ we look at are those of both body and mind produced by the pressures of modernity: stress, overwork, and information overload, but also ‘diseases of impure air’, and all the problems created for health by smoke pollution and insanitary living conditions. Ruskin, together with his friend Henry Acland, who was Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford, form part of this picture, as do all the local ‘citizen scientists’, patiently taking daily readings of sunlight hours for years on end in order to show the effects of smoke pollution, or the vicar who encouraged all his parishioners to acquire gauges so that they could measure air quality.

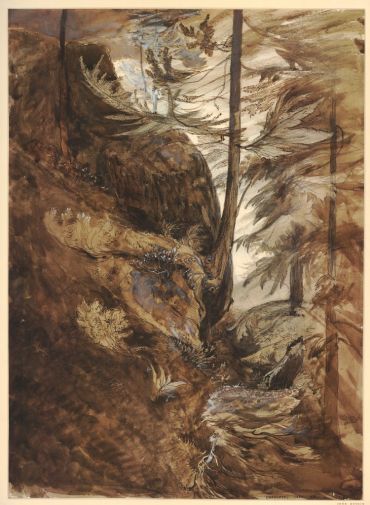

Ruskin, it has to be said, had a love-hate relationship with science: he quarrelled violently with John Tyndall over glaciers, and had contempt for Darwin’s materialism, but the close scrutiny of the natural world, upon which all his work was based, had much in common with the practices of science. To celebrate the bicentenary of his birth, we will be holding a conference on Friday 8 February at the Oxford Museum of Natural History (in partnership with the University of Birmingham Centre for Nineteenth-Century Studies), on ‘Ruskin, Science and the Environment’, to be followed at 6pm by a public lecture on ‘Ruskin’s Trees’ by Professor Fiona Stafford, author of The Long, Long Life of Trees. It is fitting that the conference is to be held in the Museum since it was built in the 1850s on principles drawn in part from Ruskin’s writings on nature and architecture, with Ruskin himself taking an active role in its design and decoration, as a tour by Professor John Holmes tour will highlight. The conference will be accompanied by an exhibition giving a rare opportunity to see designs for the museum by Ruskin and others, including the Pre-Raphaelite artists Thomas Woolner, Alexander Munro and John Hungerford Pollen.

To book for the conference click here, and here for the 6pm public lecture. Further information about both events can be found on the project website.