New Oxford study sheds light on the origin of animals

A study led by the University of Oxford has brought us one step closer to solving a mystery that has puzzled naturalists since Charles Darwin: when did animals first appear in the history of Earth? The results have been published today in the journal Trends in Ecology & Evolution.

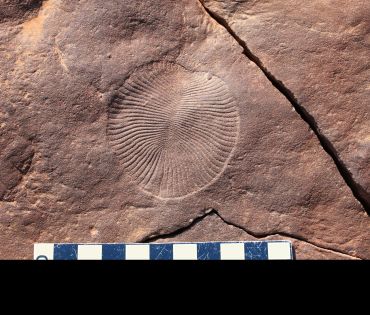

The ‘molecular clock’ method, for instance, suggests that animals first evolved 800 million years ago, during the early part of the Neoproterozoic era (1,000 million years ago to 539 million years ago). This approach uses the rates at which genes accumulate mutations to determine the point in time when two or more living species last shared a common ancestor. But although rocks from the early Neoproterozoic contain fossil microorganisms, such as bacteria and protists, no animal fossils have been found.

This posed a dilemma for palaeontologists: does the molecular clock method overestimate the point at which animals first evolved? Or were animals present during the early Neoproterozoic, but too soft and fragile to be preserved?

To investigate this, a team of researchers led by Dr Ross Anderson from the University of Oxford’s Department of Earth Sciences have carried out the most thorough assessment to date of the preservation conditions that would be expected to capture the earliest animal fossils.

To investigate this, the research team used a range of analytical techniques on samples of Cambrian mudstone deposits from almost 20 sites, to compare those hosting BST fossils with those preserving only mineral-based remains (such as trilobites). These methods included energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction carried out at the University of Oxford’s Departments of Earth Sciences and Materials, besides infrared spectroscopy carried out at Diamond Light Source, the UK’s national synchrotron.

The analysis found that fossils with exceptional BST-type preservation were particularly enriched in an antibacterial clay called berthierine. Samples with a composition of at least 20% berthierine yielded BST fossils in around 90% of cases.

Microscale mineral mapping of BST fossils revealed that another antibacterial clay, called kaolinite, appeared to directly bind to decaying tissues at an early stage, forming a protective halo during fossilisation.

‘The presence of these clays was the main predictor of whether rocks would harbour BST fossils’ added Dr Anderson. ‘This suggests that the clay particles act as an antibacterial barrier that prevents bacteria and other microorganisms from breaking down organic materials.’

Mapping the compositions of these rocks at the microscale is allowing us to understand the nature of the exceptional fossil record in a way that we have never been able to do before. Ultimately, this could help determine how the fossil record may be biased towards preserving certain species and tissues, altering our perception of biodiversity across different geological eras.

Dr Ross Anderson, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford

The researchers then applied these techniques to analyse samples from numerous fossil-rich Neoproterozoic mudstone deposits. The analysis revealed that most did not have the compositions necessary for BST preservation. However, three deposits in Nunavut (Canada), Siberia (Russia), and Svalbard (Norway) had almost identical compositions to BST-rocks from the Cambrian period. Nevertheless, none of the samples from these three deposits contained animal fossils, even though conditions were likely favourable for their preservation.

Dr Anderson said: ‘Similarities in the distribution of clays with fossils in these rare early Neoproterozoic samples and with exceptional Cambrian deposits suggest that, in both cases, clays were attached to decaying tissues, and that conditions conducive to BST preservation were available in both time periods. This provides the first “evidence for absence” and supports the view that animals had not evolved by the early Neoproterozoic era, contrary to some molecular clock estimates.’

The study ‘Fossilisation processes and our reading of animal antiquity’ has been published in Trends in Ecology & Evolution.

You can learn more about the origins of animals on the First Animals section of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History website, or by viewing the museum’s ground-floor exhibits.

*‘Animals’ can be defined as multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals feed on organic matter, breathe oxygen, reproduce sexually, have specialized sense organs and a nervous system, and are able to respond rapidly to stimuli.

Expert Comment: How can we encourage engagement with online fact-checking?

Expert Comment: How can we encourage engagement with online fact-checking?

New analysis of archaeological data reveals how agriculture and governance have shaped wealth inequality

New analysis of archaeological data reveals how agriculture and governance have shaped wealth inequality