Expert Comment: Economic sanctions are not likely immediately to shift Russian opinion against Putin

There is understandably great interest in the political consequences of the economic sanctions imposed on Russia in response to the invasion of Ukraine. Will sanctions help to shift opinion against Putin and stir Russians into political action to protest the war and help end it? Or will they have the effect of leading Russians to rally round the flag and solidify Putin’s coalition?

By Professor Paul Chaisty, Professor of Russian Government, Department of Politics and International Relations and Professor Stephen Whitefield, fellow in politics.

To address these issues, we analysed the effects of sanctions on Russian public opinion using surveys we conducted in 2014 and 2018 following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014. Clearly, sanctions now are significantly more onerous – as is the intensity of the war itself – but public opinion in both waves provides a basis for considering how Russians may respond today.

We addressed three questions. First, who was most concerned about sanctions in 2014 and 2018? Second, what was the relationship between concern about sanctions and evaluations of President Putin? Third, what was the relationship between concern about sanctions and willingness to engage in political protest?

Who was concerned about sanctions?

The survey responses in 2014 and 2018 show a rather divided population (Figure 1), with sanctions concern declining over time. The latter is not surprising since Russia was able to respond effectively to the effect of sanctions. When thinking about the current situation, we should bear in mind that Russians’ prior experience of coping with sanctions might inform their responses today.

Who then was most concerned about sanctions? As can be seen in Figure 2, the key constituencies within Putin’s coalition – the economically prosperous, provincial residents and state employees – were significantly less likely to be ‘very concerned’ about sanctions.

The ‘winners’ – those who had prospered most under Putin – were around 25% less likely than economic ‘losers’ to be concerned, in both 2014 and 2018.

Concerns about sanctions were less evident in the countryside and smaller provincial urban centres than in the metropolitan cities of St Petersburg and Moscow (around 15% less likely in both waves), and other predictors of support for Putin, notably state employment and age, were not negatively affected by sanctions. Therefore, we find little indication of negative sanction effects on Putin’s coalition.

How did concern about sanctions relate to evaluations of Putin?

Concern about sanctions did have a direct negative effect on willingness to vote for Putin (see Figure 3). However, the effect was relatively modest in 2014 when Putin’s appeal was socially widespread, following Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

The picture changes somewhat by 2018, as Figure 3 also shows. Sanctions continued to suppress support for Putin modestly, but other social factors gained greater significance in determining support or opposition to Putin, a sign that the consensus around the annexation of Crimea was crumbling. However, we find no evidence that concern about sanctions made his opponents on these other social dimensions – economic losers, the young – any more anti-Putin.

How did concern about sanctions relate to willingness to protest?

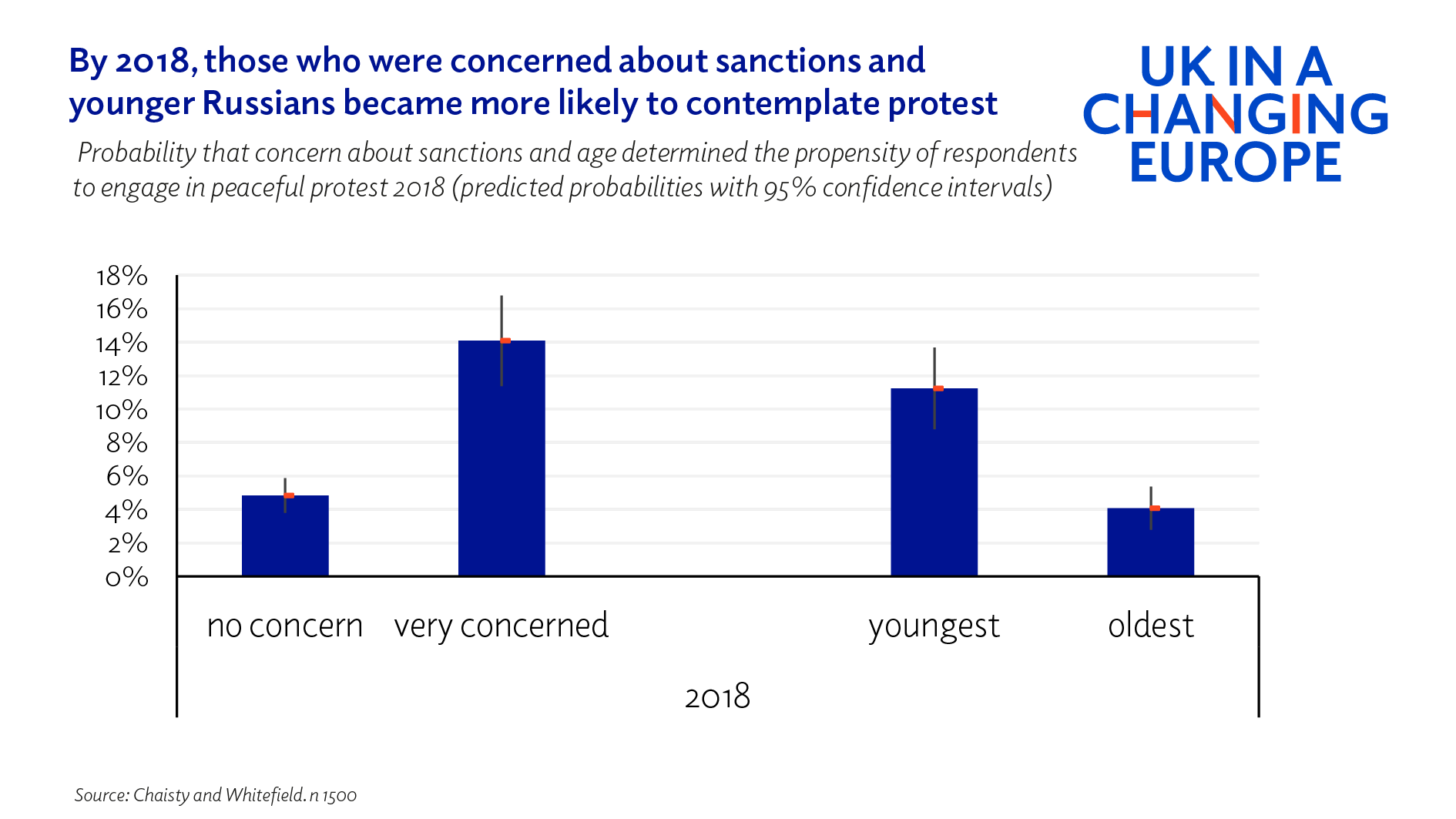

In 2014, there was a weak and negative effect of sanctions on the propensity of respondents to protest. Consistent with the idea of the Crimean consensus the other social predictors – affluence, residence, employment, age – had weak effects, too.

By 2018, those who were concerned about sanctions became more likely to contemplate protest (see Figure 4), but, as with the analysis above, we do not find that sanctions interacted with any other social predictor, including age, in driving this willingness to protest.

Conclusions

Concerns about sanctions affected some citizens more than others, but they did not appear to impact negatively on Putin’s broad societal coalition. There is some evidence that their political effects strengthened over time, especially on support for Putin and willingness to protest, but they did not interact with other social predictors to magnify opposition to Putin.

Therefore, insofar as attitudes from 2014 and 2018 are a guide to the present context, our analysis suggests that the political effects of current sanctions may be modest, at least in the short term.

The Russian regime has a strong narrative of its own to explain the war as a response to Western aggression against the country’s ‘legitimate’ (in the minds of the war’s proponents) entitlement to Ukrainian territory. This is a view that state-controlled media reinforces. While there are certainly many Russians who are hostile to the war, sanctions are not likely to affect the bulk of opinion. If anything, a ‘rally round the flag’ response may occur. Moreover, while sanctions may erode support for Putin in the medium term, they may not lead to mass defection from him. Those most concerned about sanctions may be more inclined to protest, but any such protest will take place in an increasingly repressive political environment.

Clearly, the current sanctions regime is harsher than was the case before, and so the effects on Russians might make them more likely to oppose the regime in their attitudes and perhaps their behaviour. But, there appears a much deeper well of regime support than hopeful Western observers might expect. This support may erode but only over time.

Originally published on the UK in a Changing Europe website.

Oxford Humanities team delivers framework for tackling modern slavery and human trafficking

Oxford Humanities team delivers framework for tackling modern slavery and human trafficking

Nearly 500,000 children could die from AIDS-related causes by 2030 without stable PEPFAR programmes, Oxford experts estimate

Nearly 500,000 children could die from AIDS-related causes by 2030 without stable PEPFAR programmes, Oxford experts estimate

Expert Comment: Why has Trump launched so many tariffs and will it cause a recession?

Expert Comment: Why has Trump launched so many tariffs and will it cause a recession?