Oxford University Press

Can fiction and academic writing help each other?

Elleke Boehmer is Professor of World Literature in Oxford University's Faculty of English Language and Literature. She is also a published novelist. She has recently brought out a novel and will publish a major academic book in September. Professor Boehmer tells Arts Blog that each kind of writing can help the other.

AB: Your latest novel, The Shouting in the Dark (Sandstone Press), has just been published. Is it difficult to write fiction alongside writing academic books?

EB: Yes, the business of producing more than one kind of writing probably does look challenging, and there definitely are different demands on your energy and focus when you're writing fiction as against when you're writing academic books.

In fiction, there is more of a demand to keep the writing concentrated in whatever centre of consciousness, of the character or the narrator, that you as a writer are dealing with. In The Shouting in the Dark this definitely is the case, and I reworked the book nearly twenty times to get it absolutely right.

In academic writing the push is to stand a little to the side of the material and analyse. But ultimately in both kinds of writing, the thinking is happening through the writing. My gut feeling is that similar parts of the brain are firing.

It took me a while to come to this understanding though. I've been writing fiction alongside non-fiction for over 25 years now, and at first I did tend to think two different kinds of processes were involved. Thinking that used to make me feel very tired!

Can writing fiction improve your non-fiction writing or are they very separate things?

Definitely the different kinds of writing can help each other out. The things you learn about controlling language, and the structure of 'thought units', like paragraphs, work across and between the different strands.

Are there ways in which your research has informed your novels?

Yes, research does inform my novels, especially when I get fascinated by a topic I'm researching, but this isn't always beneficial for the fiction. One of my novels, Bloodlines, published in 2000, had as its imaginative springboard the fact that Irish republican soldiers fought in the Anglo-Boer War in 1899-1902, and mingled while in the Transvaal with local people.

I got stuck into a huge amount of research, including in the National Library of Ireland, which was very enjoyable, but in the end the research perhaps weighed too heavily on the story element.

Marina Warner calls this the green light of the study lamp shining through. With fiction, character or voice has to convince, not the scholarship.

Your next academic book, Indian Arrivals, 1870-1915 (OUP), comes out in September. What is it about?

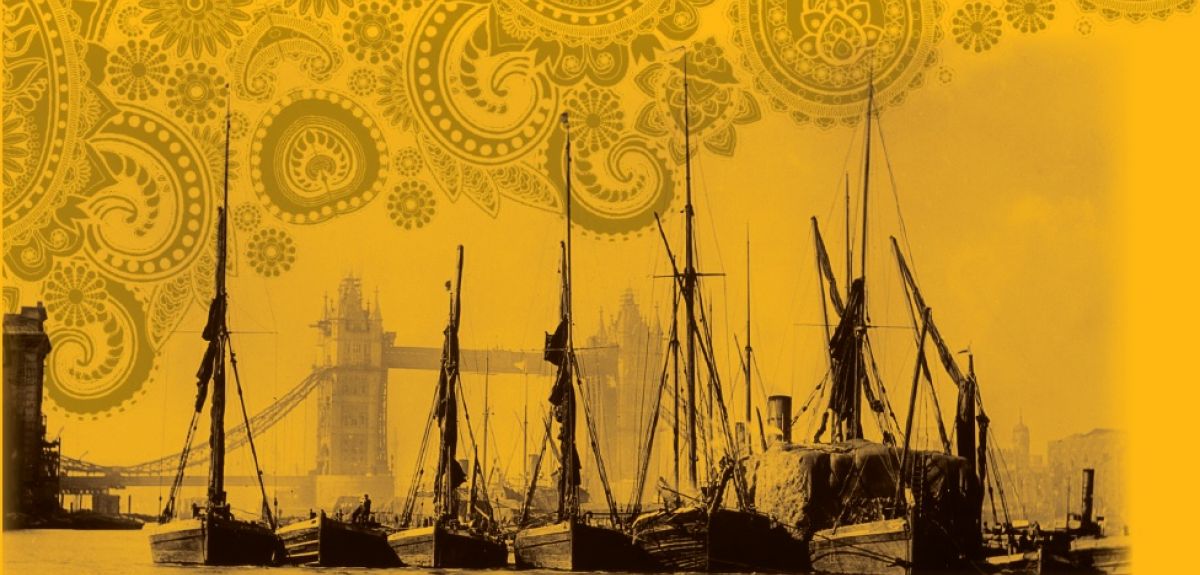

Indian Arrivals 1870-1915 is about turn of the century Indian travellers who wound their way through Suez to Britain, and the interesting and unexpected impacts that had on cultural and literary life over here, including shaping London's sense of itself as cosmopolitan and modern.

If, as is now widely accepted, vocabularies of inhabitation, education, citizenship and the law were in many cases developed in colonial spaces like India, and imported into Britain, then, the book suggests, the presence of Indian travellers and migrants needs to be seen as much more central to Britain’s understanding of itself, both in historical terms and in relation to the present-day.

The book demonstrates how the colonial encounter in all its ambivalence and complexity inflected social relations throughout the empire, including at its heart.

What sources did you use when researching the book?

Particularly useful sources were the manuscripts of the poets Sarojini Naidu and Rabindranath Tagore, which revealed how their work was frequently composed and translated en route, while travelling, and often on ships, so their works literally were 'travelling' documents.

I also read many English language newspapers of the time, including from India, which showed how cosmopolitan educated Indians felt they were, even when they hadn't yet left their homeland. The censuses of 1901 and 1911 were also very revealing, reflecting how surprisingly many people with Indian surnames lived around Britain's docklands at this time.