Image credit: Maya2008/ Shutterstock

Good news for people with osteoporosis

When it comes to your bone health, the benefits of alendronate outweigh the risks, Associate Professor Daniel Prieto-Alhambra from the Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences tells Jo Silva

As an Associate Specialist in Metabolic Bone, I welcome strong evidence-based guidance on the safety of medication I'm likely to prescribe to my patients. As a clinical researcher, sometimes I get to answer my own questions.

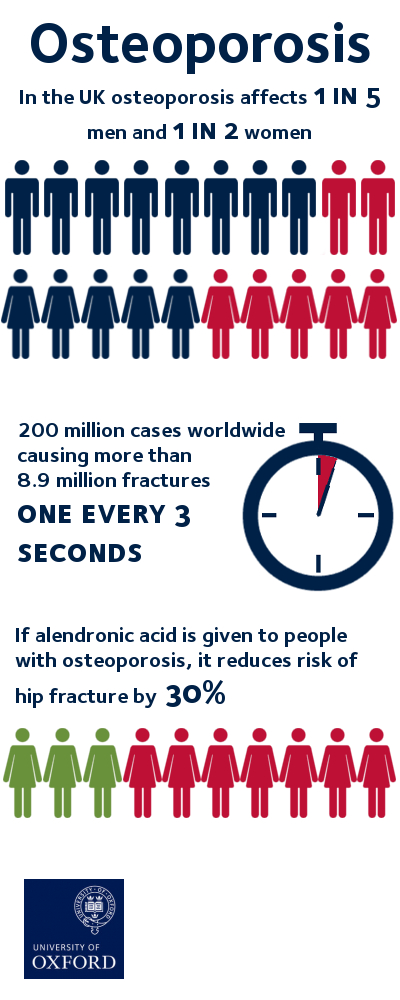

Worldwide, osteoporosis affects more than 200 million people and causes more than 8.9 million fractures annually, resulting in an osteoporotic fracture every 3 seconds.

In the UK, 1 in 2 women and 1 in 5 men over 50 will suffer a fracture related to osteoporosis, making it a much more common condition than other diseases which usually catch public attention, like breast or prostate cancer.

Currently, alendronate – a bisphosphonate drug – is one of the most common medications for osteoporosis, but prescription rates have declined by 50% in both the US and the EU amid fears of its potential risks of it leading to more (the so-called atypical) fractures.

This was bad news for osteoporosis patients. With it being the first line therapy, it was crucial to investigate the effects of taking alendronate for a long time. This can inform doctors and support patients to understand their treatment and options.

By using the Danish prescription registry, we are closer to an answer on the benefit/risk cost of alendronate. Holding almost 20 years of drug exposure data for all residents in the country, the registry can also be linked to all fractures treated in hospital in the same period.

The results of our study into alendronate using the Danish registry were recently published in the BMJ and suggest that taking this medication for over 10 years is associated with a reduced risk of hip fracture by 30% whilst not increasing other femoral fractures overall – both are excellent news to patients worldwide, as well as doctors tasked with prescribing suitable medication for their patients, like me.

How we did our study

We used anonymised records on hospital contacts and drug dispensations in the whole of Denmark.

From there, we identified all users of alendronate, and we followed them for as long as available (more than 10 years for some) until they fractured their hip or other parts of their femur. We then matched these fracture cases to non-fractured alendronate users to then study the association between drug use - long versus short-term use, and high versus low compliance - and fracture risk.

What's next?

The main limitation of our study is its observational nature, meaning that patients were not randomly allocated to treatment but prescribed treatments based on clinical recommendations.

In addition, there are other potential side effects like osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) that need quantification within the same cohort. We are now therefore working on an analysis of the risk of ONJ in this same population, which we hope to report upon in the coming few months.