Black hole trio hope for gravity wave hunt

The discovery of three closely orbiting supermassive black holes in a galaxy more than four billion light years away could help astronomers in the search for gravitational waves: the 'ripples in spacetime' predicted by Einstein.

An international team, including Oxford University scientists, led by Dr Roger Deane from the University of Cape Town, examined six systems thought to contain two supermassive black holes. The team found that one of these contained three supermassive black holes – the tightest trio of black holes detected at such a large distance – with two of them orbiting each other rather like binary stars. The finding suggests that these closely-packed supermassive black holes are far more common than previously thought.

A report of the research is published in this week's Nature.

Dr Roger Deane from the University of Cape Town said: 'What remains extraordinary to me is that these black holes, which are at the very extreme of Einstein's Theory of General Relativity, are orbiting one another at 300 times the speed of sound on Earth. Not only that, but using the combined signals from radio telescopes on four continents we are able to observe this exotic system one third of the way across the Universe. It gives me great excitement as this is just scratching the surface of a long list of discoveries that will be made possible with the Square Kilometre Array (SKA).'

Professor Matt Jarvis of Oxford University's Department of Physics, an author of the paper, said: 'General Relativity predicts that merging black holes are sources of gravitational waves and in this work we have managed to spot three black holes packed about as tightly together as they could be before spiralling into each other and merging. The idea that we might be able to find more of these potential sources of gravitational waves is very encouraging as knowing where such signals should originate will help us try to detect these ‘ripples’ in spacetime as they warp the Universe.'

The team used a technique called Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) to discover the inner two black holes of the triple system. This technique combines the signals from large radio antennas separated by up to 10,000 kilometres to see detail 50 times finer than that possible with the Hubble Space Telescope. The discovery was made with the European VLBI Network, an array of European, Chinese, Russian and South African antennas, as well as the 305 metre Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Future radio telescopes such as the SKA will be able to measure the gravitational waves from such black hole systems as their orbits decrease.

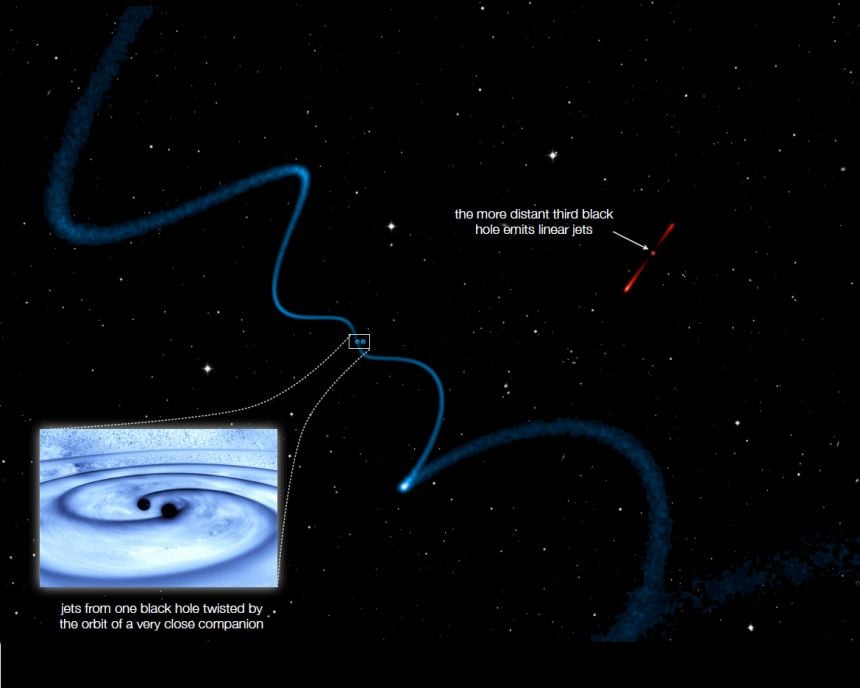

Helical jets from one supermassive black hole caused by a very closely orbiting companion (see blue dots). The third black hole is part of the system, but farther away and therefore emits relatively straight jets.

Helical jets from one supermassive black hole caused by a very closely orbiting companion (see blue dots). The third black hole is part of the system, but farther away and therefore emits relatively straight jets.At this point, very little is actually known about black hole systems that are so close to one another that they emit detectable gravitational waves. Professor Jarvis said: 'This discovery not only suggests that close-pair black hole systems emitting at radio wavelengths are much more common than previously expected, but also predicts that radio telescopes such as MeerKAT and the African VLBI Network (AVN, a network of antennas across the continent) will directly assist in the detection and understanding of the gravitational wave signal. Further in the future the SKA will allow us to find and study these systems in exquisite detail, and really allow us gain a much better understanding of how black holes shape galaxies over the history of the Universe.'

Dr Keith Grainge of the University of Manchester, an author of the paper, said: 'This exciting discovery perfectly illustrates the power of the VLBI technique, whose exquisite sharpness of view allows us to see deep into the hearts of distant galaxies. The next generation radio observatory, the SKA, is being designed with VLBI capabilities very much in mind.'

While the VLBI technique was essential to discover the inner two black, the team has also shown that the binary black hole presence can be revealed by much larger scale features. The orbital motion of the black hole is imprinted onto its large jets, twisting them into a helical or corkscrew-like shape. So even though black holes may be so close together that our telescopes can’t tell them apart, their twisted jets may provide easy-to-find pointers to them, much like using a flare to mark your location at sea. This may provide sensitive future telescopes like MeerKAT and the SKA a way to find binary black holes with much greater efficiency.

The UK team included researchers from Oxford University, the University of Manchester, and the University of Cambridge. A report of the research, entitled 'A close-pair binary in a distant triple supermassive black-hole system', is published in this week's Nature.

Former UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to join Blavatnik School of Government’s World Leaders Circle

Former UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to join Blavatnik School of Government’s World Leaders Circle

Wellcome Discovery Award of £5m to fund pioneering research to combat deadly diarrhoea

Wellcome Discovery Award of £5m to fund pioneering research to combat deadly diarrhoea

The Global Health Network reaches 1 million members

The Global Health Network reaches 1 million members

First patients scanned in new study investigating traumatic brain injury in young athletes

First patients scanned in new study investigating traumatic brain injury in young athletes

BMI, blood pressure and physical activity levels in childhood linked to brain differences

BMI, blood pressure and physical activity levels in childhood linked to brain differences