Engineering a better world

Despite being one of the most fast evolving sciences in many ways, gender equality is one area where the field of engineering is playing catch-up. But, in spite of this continued imbalance, little by little, female engineers are shaping the world around us with their research achievements, developing scientific solutions to real world challenges.

In celebration of International Women in Engineering Day (June 23) – an initiative intended to raise the profile of women in engineering and physical sciences and encourage other budding scientists to join them, we wanted to shine a light on a female academic engineering a difference at Oxford.

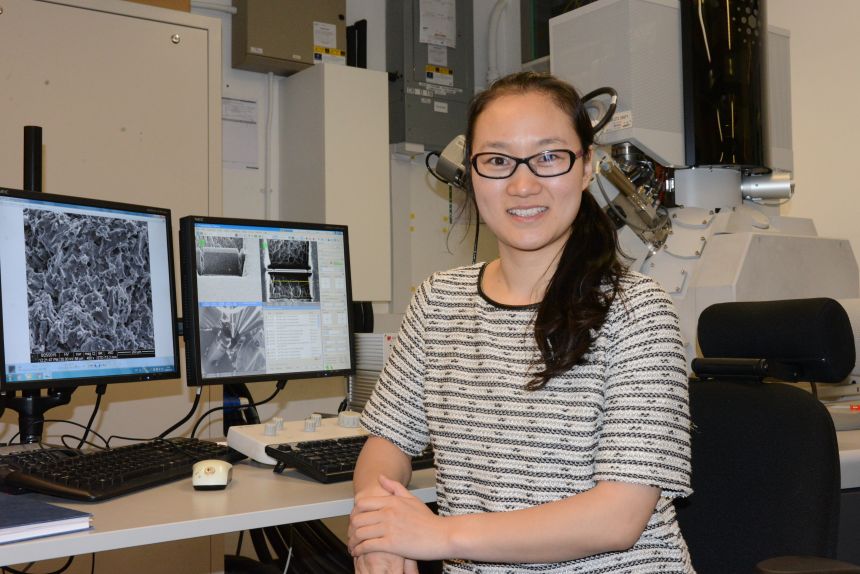

Dr. Dong Liu is an independent research fellow at Oxford’s Department of Materials and a Soapbox Science ambassador. Specialising in materials sciences, physical sciences and mechanical engineering, Dr Liu’s research is focused on better understanding of new materials for nuclear reactors and how this can drive further developments in nuclear energy production.

For those that are not familiar, what is Materials Science – and how does it differ from Engineering in general?

To make any effective device, structure or product, you need the right material(s). Materials Science is the study of all materials – from the things you use every day like plastics, glass and sports and health care equipment, to more industrial appliances in aircrafts, space shuttles and nuclear reactors.

I am interested in how materials react to extreme conditions, for example, inside a jet engine or a reactor core, where heat and irradiation is a problem. Understanding how and why the materials degrade and break is key to designing and making stronger materials. Compared with Engineering, Materials Science focuses more on the mechanisms of the material failure. By gaining this knowledge, we can understand their engineering behaviour better.

By understanding a material’s strengths and weaknesses we can optimise its use and eventually make our nuclear energy sources more efficient and effective.

Which material does your research focus on?

My primary research interest is on ceramic-like materials used in aero-engines, e.g. ceramic coatings on turbine blades protecting them from the heat of the engine, and a material called graphite used in the core of nuclear reactors at power plants in the UK and some other countries.

What is graphite?

Nuclear grade graphite is used as the core of all 14 operating reactors that provide about 20% of the total electricity in the UK. It is much purer than materials used day to day, such as lead in pencils, so it’s ideal for building the core of nuclear reactors - a lesser material would interfere with the reactions.

What does your research involve?

Once installed, the graphite core cannot be taken out or replaced, so if it becomes unstable or develops cracks, we have to shut down the reactor. I study these cracks and work to understand why stability issues occur in general. By understanding a material’s strengths and weaknesses we can optimise its use and eventually make our nuclear energy sources more efficient and effective.

Working together with my colleagues at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, we heated our nuclear graphite to more than 1000°C to test the tolerance of the material. We found that the material actually becomes stronger in high temperature environments and was less likely to fracture when heated up.

What impact has this research achievement had on your career?

Publishing our paper in Advance Science has boosted my reputation in the nuclear graphite research community and allowed me more international research opportunities.

The material is used in nuclear reactors in many other countries, including Europe, USA and China, where they are working to build the next generation of reactors, which are more powerful and environmentally friendly than previous models. I am supporting this work, analysing different grades of graphite material so that we can understand and use their tolerance levels to create a superior nuclear reactor that enables clean energy.

How did you come to specialise in this area?

I am excited by research that has an industrial imperative, it makes me feel that I am solving a real problem that is related to everyday life and helps our society.

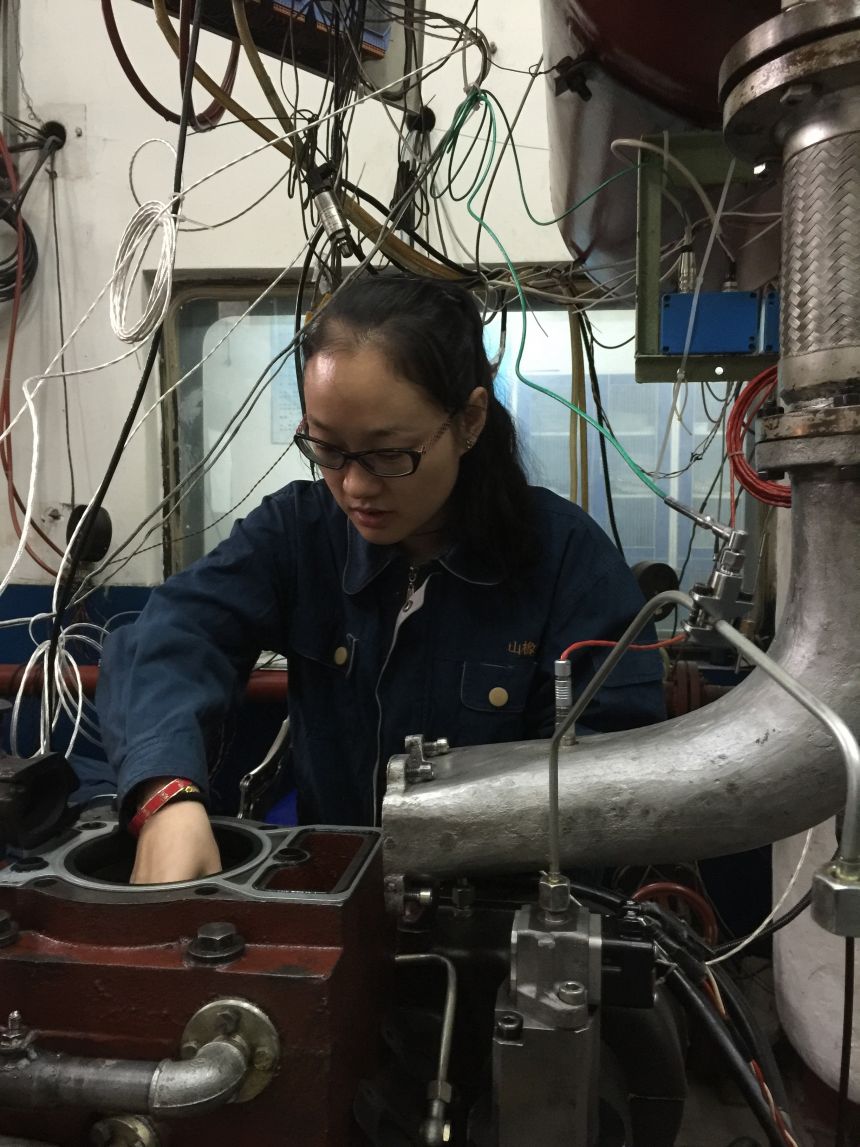

Some people assume that research is dull, but scientific engineering is all about getting your hands dirty. Taking things apart and blasting them with boiling hot X-rays is all in a day’s work for me, and I love it.

What drew you towards a career in science?

Education is very important in China and my parents played an important role in my passion for academia. Even at primary school my mum said to me; ‘you have to get a Doctorate degree when you are older’, so I have always had that goal.

I’ve always believed that a burning desire to learn is the most powerful driving force in life. When I look at where I am now, I know that I have made the right decisions.

What has surprised you most in your career?

I used to think that working in science would be lonely and I would be stuck in a lab on my own 24/7. But, communication is a big part of the job, and collaboration is key to overcoming challenges.

Some people assume that research is dull, but scientific engineering is all about getting your hands dirty. Taking things apart and blasting them with boiling hot X-rays is all in a day’s work for me, and I love it!

What advice would you give to anyone beginning or considering a career in academic science?

Be brave, take as many opportunities as you can and keep an open mind. Being a scientist is about more than publishing papers and experiments. You are part of a community that has a responsibility for influencing people’s science perceptions and understanding.

I am involved in the Nuclear Institute’s Woman in Nuclear (WiN) initiative and in organising Oxford Soapbox Science events - the national initiative to make science more accessible to the general public and raise the profile of female scientists.

Another tip is to be aware of independent research opportunities – such as funded research fellowships. I have had two while at Oxford: 1851 Royal Commission Research Fellow (Brunel) and another with the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

Fellowships have been key to my career, and helped me to grow as an independent young academic. You are the leader, the worker and the negotiator for your own research – effectively you ‘run the show.’ Applications can be competitive and time consuming, but the pay-off is worth it.

How has your experience as a women in engineering shaped your career?

For me, being a young woman in Engineering has shaped my career. It is great to be young, but in academia youth isn’t always a good thing. People often assume that you must be older to practice good science, or to have a senior position. Male or female, being or looking younger can lead to your work being challenged, so you need to really know your stuff and prove yourself

From a positive perspective being challenged only makes you get better at what you do. Before I came to Oxford as an independent researcher, if someone had asked me if I was ready for a permanent position I would have panicked. But, my experience has improved my confidence in my teaching.

What do you think are the barriers to entry for women in STEM?

Stereotypes are a big issue. A student of mine once told me that her mother has a doctorate degree, but people always assume that the Doctor in her family must be her father.

Statistically less women are applying for jobs in science and engineering compared to men, which is why it’s so important to mentor young people to encourage them to take a science / engineering career.

I believe that everyone is equal and can make important contributions to science. A diverse workforce is needed to represent the multiple facets of knowledge, perspectives and values required to uncover the most significant findings.

How do you balance the stresses of work and home life?

Any work - science or otherwise, is like a marathon rather than a sprint. My philosophy is work hard play hard and I do lots of sports like kickboxing and hiking with friends in the sunshine.

What is next for you?

I am coming to the end of my Fellowships and will soon start a permanent Lectureship position with the School of Physics at Bristol University.

I feel really lucky to have been able to stay in academic science as long as I have and I feel it is my duty to raise awareness of women working in the sciences, sharing our cool research and letting others know that they can do this too.

What will you miss most about Oxford?

There is so much I will miss, but especially the people that I work with in the Materials Department - they are like extended family. I have lots of collaborative research coming up, so I will continue to be a visiting academic at Oxford.

I’ll miss the delicious, formal Mansfield College dinners, which are out of this world and great for networking - you never know who you are going to meet at the table. I recently met Professor Katherine Blundell who specialises in Astrophysics. She is so inspiring person and good at explaining complex science, she makes me think about how I can better communicate my own work.

View Dr Liu's paper 'Damage tolerance of nuclear graphite at elevated temperatures' here