Males and females are programmed differently in terms of sex

The evolutionary biologist Olivia Judson wrote, ‘The battle of the sexes is an eternal war.’

Males and females not only behave differently in terms of sex, they are evolutionarily programmed to do so, according to a new study from Oxford, which found sex-specific signals affect behaviour.

Males and females not only behave differently in terms of sex, they are evolutionarily programmed to do so

The new study from Oxford’s Goodwin group from the Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics says, despite sharing very similar genome and nervous system, males and females ‘differ profoundly in reproductive investments and require distinct behavioural, morphological, and physiological adaptations’.

The team argues, ‘In most animal species, the costs associated with reproduction differ between the sexes: females often benefit most from producing high-quality offspring, while males often benefit from mating with as many females as possible. As a result, males and females have evolved profoundly different adaptations to suit their own reproductive needs.’

Males and females have evolved profoundly different adaptations to suit their own reproductive needs

The question for the researchers was: how does selection act on the nervous system to produce adaptive sex-differences in behaviour within the bounds set by physical constraints, including both size and energy, and a largely shared genome?

Today’s study offers a solution to this long-standing question by uncovering a novel circuit architecture principle which allows deployment of completely different behavioural repertoires in males and females, with minimal circuit changes.

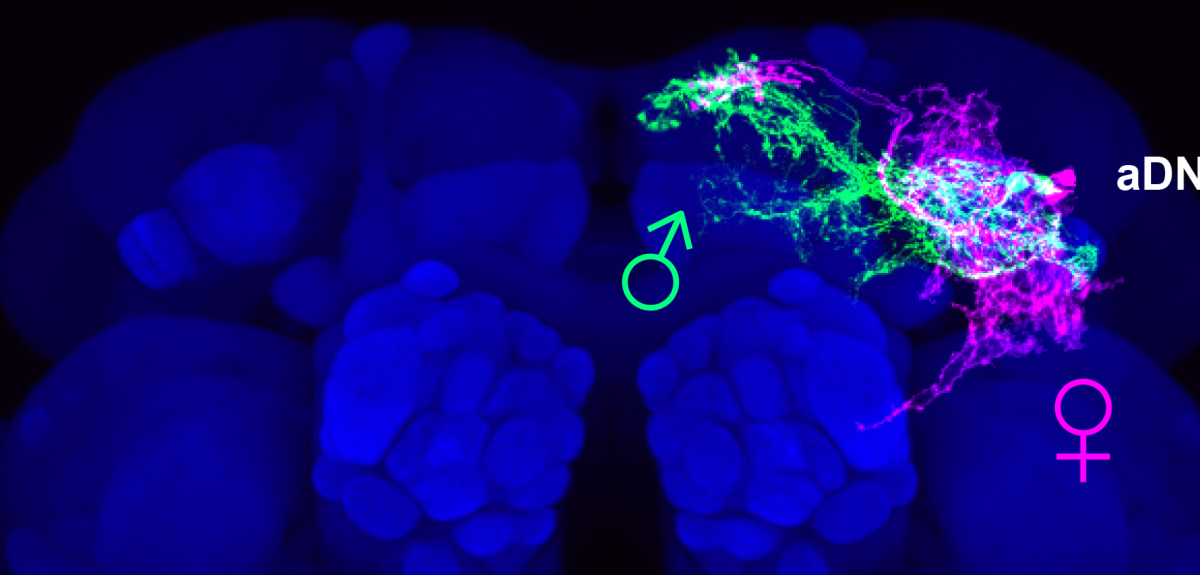

The research team, led by Dr Tetsuya Nojima and Dr Annika Rings, found that the nervous system of vinegar flies, Drosophila melanogaster, produced differences in behaviour by delivering different information to the sexes.

In the vinegar fly, males compete for a mate through courtship displays; thus, the ability to chase other flies is adaptive to males, but of little use to females. A female’s investment is focused on the success of their offspring; thus, the ability to choose the best sites to lay eggs is adaptive to females.

When investigating the different role of only four neurons clustered in pairs in each hemisphere of the central brain of both male and female flies, the researchers found the sex differences in their neuronal connectivity reconfigures circuit logic in a sex-specific manner. In essence, males received visual inputs and females received primarily olfactory (odour) inputs. Importantly, the team demonstrated that this dimorphism leads to sex-specific behavioural roles for these neurons: visually guided courtship pursuit in males and communal egg-laying in females.

In essence, males received visual inputs and females received primarily olfactory (odour) inputs

These small changes in connectivity between the sexes allowed for the performance of sex-specific adaptive behaviour most suited to these reproductive needs through minimal modifications of shared neuronal networks. This circuit principle may increase the evolvability of brain circuitry, as sexual circuits become less constrained by different optima in male and females.

And it works, the study says, ‘Ultimately, these circuit reconfigurations lead to the same end result—an increase in reproductive success.

'Our findings suggest a flexible strategy used to structure the nervous system, where relatively minor modifications in neuronal networks allow each sex to react to their surroundings in a sex-appropriate manner.'

Furthermore, this is the first time a firm link between sex-specific differences in neuronal networks have been explicitly linked to behaviour.

According to Professor Stephen Goodwin, 'Previous high-profile papers in the field have suggested that sex-specific differences in higher-order processing of sensory information could lead to sex-specific behaviours; however, those experiments remained exclusively at the level of differences in neuroanatomy and physiology without any demonstrable link to behaviour. I think we have gone further as we have linked higher-order sexually dimorphic anatomical inputs, with sex-specific physiology and sex-specific behavioural roles.'

We have linked higher-order sexually dimorphic anatomical inputs, with sex-specific physiology and sex-specific behavioural roles

Professor Stephen Goodwin

The researchers maintain ‘evolutionary forces’ have driven these adaptations, ‘Drosophila, males compete for a mate through courtship displays, while a female’s investment is focused on the success of their offspring.’

They conclude, ‘In this study, we have shown how a sex-specific switch between visual and olfactory inputs underlies adaptive sex differences in behaviour and provides insight on how similar mechanisms maybe implemented in the brains of other sexually-dimorphic species.’