How short is your time?

Our perception of time can depend on a number of factors – what we’re doing, how much we’re focusing on it, how we’re feeling. But there's also quite a bit of variability between us in our individual sense of time passing.

Researchers at Oxford University have investigated what plays a part in our perception of short, fleeting times of under a second.

In a new paper published today in the Journal of Neuroscience, they show that levels of a chemical in the brain – a neurotransmitter called GABA – accounts for some of the difference in our perceptions of subsecond intervals in what we’re seeing.

Oxford Science Blog asked Dr Devin Terhune of the Department of Experimental Psychology about the study. So depending on who you are and your judgement of time, if you have somewhere between 2 and 5 minutes to spare, read on.

OxSciBlog: Why is perception of time important to understand?

Devin Terhune: Our ability to perceive duration is one of the most fundamental features of conscious experience and thus it is of great importance to our emerging understanding of how the brain generates consciousness. Second, time perception is necessary for a wide range of abilities, from playing sports and musical instruments to day-to-day decision-making. Studying time perception has considerable potential to greatly inform the broader domains of psychology and neuroscience.

OSB: What can influence time perception?

DT: A variety of factors can affect our perception of time. Two common factors are attention and emotion. If we focus on something, time seems to slow down somewhat (hence the common phrase 'a watched kettle never boils'), whereas it seems to go by faster if we're daydreaming or thinking about something else. In contrast, we tend to overestimate time when we’re frightened, or underestimate it when we’re experiencing joy.

OSB: Tell us about the sort of time perception you investigated in this study

DT: We studied people's perception of short durations of visual images lasting around half a second.

In the specific task we used, participants were first trained on a particular image that lasted around half a second. Subsequently, they saw the same image for a range of different intervals – some shorter, some longer. Participants were asked whether each image was shorter or longer in duration than the trained interval. This task allowed us to determine whether someone is underestimating or overestimating the duration of the images, as well as their precision in the task.

OSB: And this judgement of time can be affected by the way neurons in the brain respond to what we are seeing?

DT: A number of studies have recently shown that when neurons in visual regions of the brain 'fire' more strongly, a person is more likely to overestimate the duration of a visual event, whereas when the neurons 'fire' less, they are more likely to underestimate the event. Accordingly, different ways of altering these firing responses may thus affect time perception.

OSB: What did you find?

DT: Our study showed that participants' tendency to under- or over-estimate how long the image lasted was associated with a particular neurotransmitter in the brain known as GABA.

Individuals who tended to underestimate the visual intervals were found to have higher GABA levels in the region of the brain responsible for visual processing.

Importantly, GABA levels in a second region of the brain that supports movement and motor functions were unrelated to time perception. Also, GABA levels in the visual area were unrelated to time perception in a non-visual task.

These results suggest that GABA levels in visual regions of the brain may account for variability in our perception of visual intervals.

OSB: What does this suggest is going on in the brain?

DT: We believe that higher GABA levels results in a greater reduction of the firing of neurons in response to a visual image, leading to underestimation.

OSB: Do we as individuals really differ in how we perceive time and events?

DT: It's intuitive to think that our perception of the world is similar to others, but just like many other conscious visual experiences, there is considerable variability in our ability to perceive time. This variability is more apparent for longer intervals – for instance, we all have friends who say they were only gone for two minutes when it was actually closer to ten. This variability is present for very short intervals too.

OSB: Could this tell us anything about our perception of time in everyday situations?

DT: This finding may account for why some people are better at judging very short durations than others. Since we used particular types of images in the lab, we have to be careful about how much we can generalize. However, these very short intervals are important to a range of tasks. For instance, running to catch a ball requires you to estimate when the ball will arrive in a particular location that you can reach. Similarly, when playing a musical instrument as part of an orchestra or band, it is important that you can accurately judge the specific time at which you need to play a particular note.

OSB: Is it wrong to feel slightly unsettled that what we experience and think to be an accurate representation of time passing may not be?

DT: At first glance, it could be somewhat unsettling. However, in the grand scheme of things, the vast majority of people have decent time perception. It's just that some of us are better than others, just like in a range of other cognitive, motor, and perceptual functions. Some of us have better attention or memory than others, some of us are better at riding bicycles, and so on.

Tamiflu: an analysis of all the data

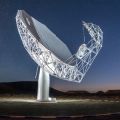

Tamiflu: an analysis of all the data MeerKAT is shape of things to come

MeerKAT is shape of things to come Why males stray more than females

Why males stray more than females