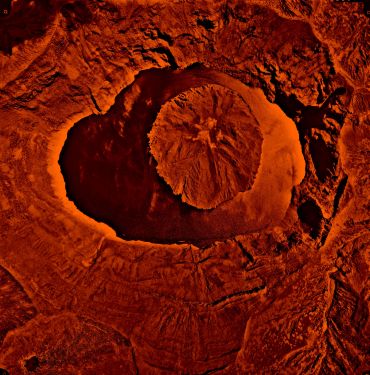

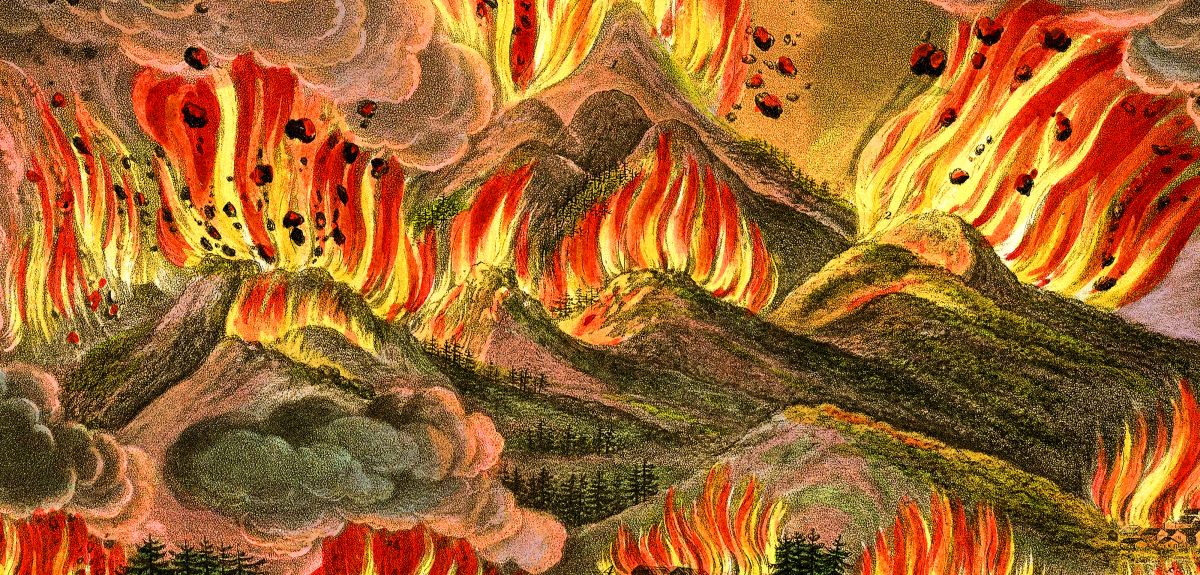

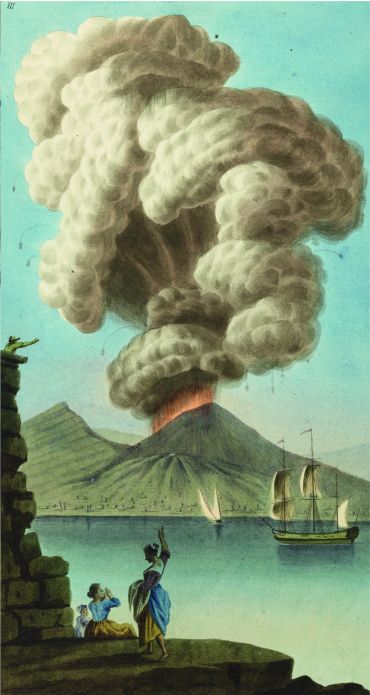

An illustration of the 1783 eruption of Mount Asama in Japan found in the book Illustrations of Japan published in London in 1822. The book was authored by Isaac Titsingh, a Dutch surgeon, scholar, merchant-trader and ambassador. He ran a Dutch trading post near Nagasaki, Japan, and avidly gathered information on the region. In September 1783 he heard news of the devastating eruption of Asama. When it reached its dreadful climax in early August, he wrote ‘the flames burst forth, with a terrific uproar … followed by a tremendous eruption of sand and stones. Everything was enveloped in profound darkness’. Several villages were reduced to ashes and 'a great number of persons were consumed by the flames.’

From the destructive to the sublime: understanding the impact of volcanic eruption

Few might connect volcanic eruptions with the Nineteenth century arts and weather change, but with its varied collection of artefacts, Volcanoes, the captivating exhibition currently running at Oxford’s Bodleian Weston Library hopes to change that. ScienceBlog met with Professor David Pyle, volcanologist and the exhibition’s curator, to find out more about how he is challenging people’s perceptions of volcanoes, and how they impact the world around us.

What was the inspiration behind the exhibit?

About three years ago, Richard Ovenden, who is now the Bodleian’s Librarian, and Madeline Slaven, Head of Exhibitions floated the idea of doing something on the theme of volcanoes. This sounded like an exciting opportunity and we took it from there.

On a personal level, my work tends to focus on the geology of volcanoes, but recent projects in Santorini, Greece and St Vincent in the Caribbean, have looked at other records of volcanic activity. People’s stories and official accounts of the effects of volcanic eruptions tend not to be included in formal science evaluations, but they can tell us a lot about their human impact. The exhibition was as a great opportunity to share this perspective and surprise people.

What kind of insights can these records offer?

The colonial records of the St Vincent eruption of 1902 are extraordinary. One thing the colonial government was good at was keeping records, and this includes correspondence between the Governor, Chief of Police and other high level officials in London. The detail you can extract from official first-hand accounts, in terms of what actually happened, and how the eruption impacted communities, opened my eyes to the wealth of information available on how people have coped with and responded to volcanic activity in the past.

Instead of just focusing on explorers’ experiences we have included elements that shed light on tourists’, travellers’ and everyday people’s encounters with volcanoes – even those who came across them by accident.

How did you decide what to include?

I looked through around 400 objects in total, and the final exhibition features 80. Everyone had a role to play, and I spent three years burrowing through the Bodleian archives.

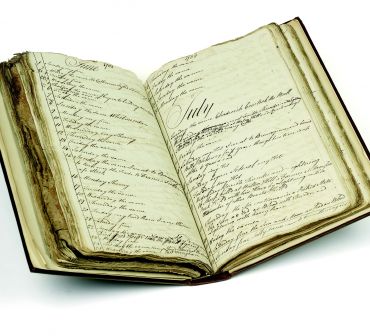

William Dunn’s diary for July 1783, recording the ‘putrid air’ across England following the eruption of Laki, a volcano in Iceland. It was only later, in the 1800s, that scientists began to understand the relationship between major volcanic eruptions and freak weather conditions that can occur hundreds of miles away from the site of the eruption.

As a volcanologist, I was in my element and found the volume of material incredible. Handling old books and manuscripts evokes a tangible connection between you, now and then, it’s an immense privilege to hold an object with such tremendous history.

I’m not sure what other people expect when they come to an exhibition called volcanoes, but I imagine people would envision vivid colours and descriptions of violent eruptions. The vivid colours are carried through the exhibition in its design, but the arts’ pieces selected show that volcanoes have had an entirely different impact socially. Instead of just focusing on explorers’ experiences – which are well documented, we have included elements that shed light on tourists’, travellers’ and everyday people’s encounters with volcanoes – even those who came across them by accident.

Can you tell us about the structure of the exhibition?

There are 10 differently sized cases in the exhibition - small, large, long, 3D etc. Of course we have the Bodleian’s printed materials (books and manuscripts etc.) and physical rock samples from the Museum of Natural History, but it also features things that you might not expect; Victorian poetry, art, film posters, match box lids and even tourist trinkets.

Which display are you most pleased with?

The volcano weather exhibit surprises people. An eruption takes place thousands of miles away, but its impact is often felt across the globe, through climate change. From fiery sunsets, to torrential storms, they have had great impact on the weather of the natural world. On the one hand there is the devastating immediate impact on the people living around the eruption, but the effect socially, on the other side of the world was entirely different, and often quite sublime.

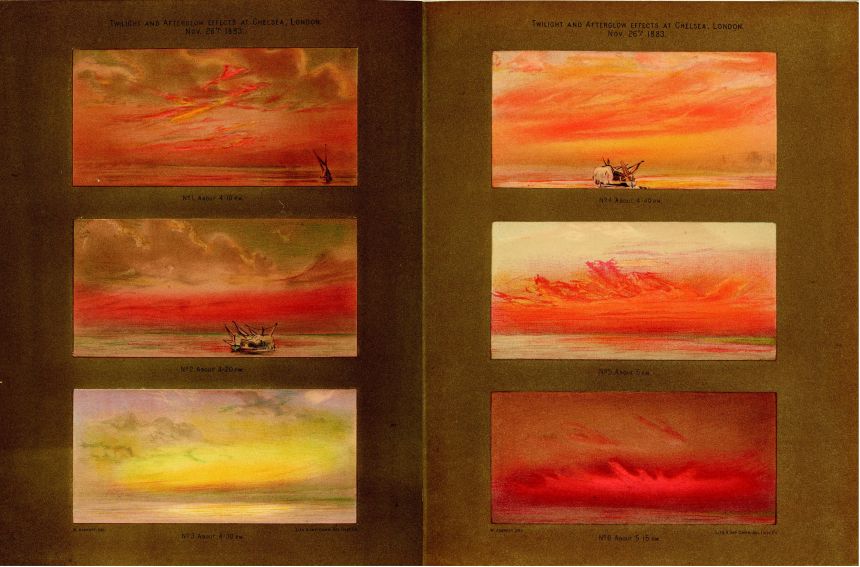

An after effect of the eruption of Mount Krakatoa in 1883 were spectacular sunsets across Europe. These sunsets were the inspiration for some of the most celebrated poetry of the time, such as Tennyson and Gerard Manley Hopkins, and stunning watercolour paintings.

People might not connect art and volcanic experience, but the sheer volume of material inspired by them, tells us a lot about international communication in the 18th century. The international telegraph network meant telegrams could be sent quickly across continents. Whether people experienced eruptions first hand, or heard about them on the social grapevine, they clearly developed their own feelings about them and expressed them in memorable ways.

William Ascroft’s watercolours of vivid sunsets seen from Chelsea, London, in autumn 1883 after the great eruption of Krakatoa in Indonesia. The image is found in a book called The eruption of Krakatoa and subsequent phenomena published in London in 1888 by Symons et al.

The weather diaries are fascinating, and show the impact of climate change physically and socially, at a time when no one really understood what it was.

Do any of the pieces tell us anything particularly interesting about how perceptions of volcanoes have changed?

The weather diaries are fascinating, and show the impact of climate change physically and socially, at a time when no one really understood what it was.

One from 1783 details the aftereffects of an eruption in Iceland, which triggered a hazy smog, so thick it could almost chock you. The diaries build a picture of an unbearably hot climate, complete with violent thunderstorms and an unusually red sun. Fast forward a few hundred years and we recognise these unusual weather conditions as air pollution induced climate change. But, at that time no one really knew about it, or had an explanation for the unusual weather, the explanations came later.

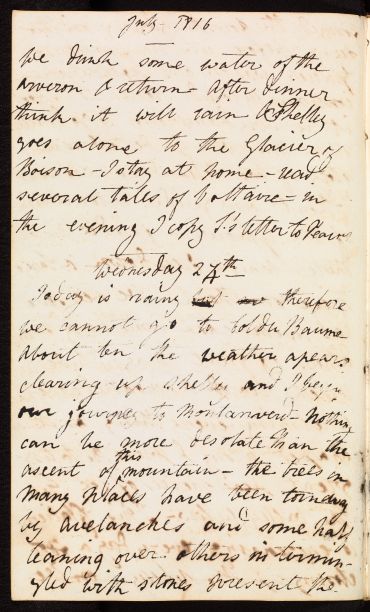

Another focuses on the impact of an eruption in 1816, which became known as the year without a summer in Northern Europe. In the Northern US conditions were so bad, it was dubbed: “Eighteen hundred and froze to death.” From the same period we have two pages of Mary Shelley’s diary, who of course wrote Frankenstein. She’s writing from Switzerland, in July 1816 - one of the worst affected places. Making these connections goes some way to explaining the morose tone and scenery depicted in the book, and the literary impact of eruptions.

A page from Mary Shelley’s journal from her entry on Wednesday 24 July 1816 when she writes of the terrible rain during her holiday at Lake Geneva. It was at this time that Shelley came up with idea for her novel Frankenstein. 1816 was known as ‘the year without summer’ due to the 18165 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia. It was only in the 1800s that scientists began to understand the relationship between major volcanic eruptions and weather conditions that can occur hundreds of miles away from the eruption site.

Favourite piece from the exhibit?

One of the most significant elements is the oldest, a carbonised scroll from Herculaneum, located in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius. It is a piece of papyrus that contains a book that would have been rolled up and stored in a library in Herculaneum. It was buried by and preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79AD. When the library was excavated in the late 1750s, the King of Naples gave away some of these scrolls to passing dignitaries, one of whom was Prince George of England, who then gifted the scroll to the Bodleian Library.

There is something quite special about holding a volcano exhibition in a library, where the oldest item in the show is also from a library, and was preserved because of a volcanic eruption.

Storytelling is a powerful way of communicating how volcanoes behave, and starting conversations about how society can prepare for an unexpected eruption.

How did you come to be a volcanologist?

I saw my first volcano aged seven, when my family lived in Chile for a year, and I have been obsessed ever since. It’s a place where you can’t escape mountains and there are volcanoes everywhere, including my favourite, Villarrica. I’ve been back as adult, and fulfilled my childhood dream of climbing the summit and peering into the crater.

What is your proudest achievement to date?

An academic’s career is long and potentially lonely, so you have to celebrate everything along the way. I don’t look back on anything that I have done with rose tinted spectacles because there are so many things that I want to do next.

I have been very close to the exhibition for a long time, and now we have finally opened, it is delightful to see other people enjoying and responding to it.

Eruption of Vesuvius on 9 August 1779, seen from Naples. Gouache by Pietro Fabris, from the supplement to the 1779 edition of William Hamilton’s Campi Phlegraei. Hamilton (1730-1803) was a Scottish diplomat who was posted to Naples in the 18th century. From his country house at the foot of Vesuvius, Hamilton was ideally placed to witness and investigate the eruptions of the 1770s. He wrote a number of papers, books and letters documenting the 18th century eruptions of Vesuvius. Campi Phlegraei (meaning flaming fields, the local name for the area around Naples affected by Vesuvius eruptions) is a beautifully illustrated scientific treatise that contains 54 hand coloured plates by the artist Peter Fabris.

What is next for you?

My next project focuses on better telling and sharing people’s stories and experiences of volcanoes. Storytelling is a powerful way of engaging with people, communicating how volcanoes behave, and starting conversations about how society can prepare for an unexpected eruption. The official records of the St. Vincent eruption are a great testament to events, but they are not easily accessible to people actually living on the island, so impossible for them to learn from.

Storytelling is a powerful way of engaging with people, communicating how volcanoes behave, and starting conversations about how society can prepare for an unexpected eruption.

In collaboration with researchers from the University of East Anglia, who are leading a project on strengthening resilience in volcanic areas, we have been running workshops on the island, speaking to residents about their own experiences, and sharing our research.

Like many other Caribbean islands there are much more pressing needs - annual hurricane season being one of them. The volcano hasn’t actually erupted for forty years, so we were expecting it to be low on their list of priorities, but actually people have been really engaged and eager to think about it. Particularly the difference between dealing with an eruption today and forty years ago.

What is your favourite thing about your job?

It is a huge privilege to be able to work in places that are so captivating, visiting them with a purpose other than just travelling there for the sake of it. There are 60 or 80 volcanoes that erupt in any year, and often they are totally unexpected, so there is always something new to learn and look at.

• Volcanoes is running at the Bodleian Weston Library, Oxford until 21 May 2017