Features

Dr Sarah Bauermeister is a senior data and science manager at Dementias Platform UK, an MRC-funded project based at Oxford University set up to accelerate research into the diagnosis and treatment of dementia. On International Day of Women and Girls in Science, Dr Bauermeister talks to Science Blog about her route into research – including a 20-year career break to raise and home-educate her seven children.

Q: How did you get into science?

A: Before having children I completed a degree in sports science in South Africa and was intending to travel, but instead I quickly settled in the UK. Later, while home-schooling my children, I worked towards a further degree in psychology, then a master’s – both through the Open University. I specialised in cognitive neuropsychology, focusing on the neurological changes affecting cognition in older adults, and completed my PhD at Brunel University London focusing on lifestyle and fitness as moderators of cognitive decline. I then completed a postdoctoral position investigating cognitive predictors of falls and frailty at the University of Leeds.

Q: Tell us about your first job in science.

Given the competitive nature of the field and the precariousness of contracts early in scientific careers, women are hesitant to take career breaks to start a family.

A: After a 20-year period during which I studied while raising and home-educating my seven children, I became an early-career scientist in Leeds with people 20 years younger than me. I’d already had my family by that stage, but I found that many of the younger women around me felt they were in a difficult position in this respect.

Q: How can we encourage more women and girls into science?

A: There are some real barriers to women working in science. Although there is a lot of work being carried out to shift the balance, reports show that institutions, research groups and individual scientists still support men in their careers more than women. In too great a proportion of research groups you see the group leader is a man and the postdoctoral researchers are women. This is disheartening, because it shows that many talented women were not mentored or encouraged to stay in science, or given the right support either to return after raising a family or to combine working with raising a family. This type of support is crucial if we want to retain women in this field.

It is no longer up to women to push equality – it needs to come from the top, and then this would filter down so that the main income is no longer gender-specific. Only with this type of policy change will equality of care be feasible for families.

Q: What changes need to happen?

A: We need to start by changing the culture in schools, as well as in higher education. The intake of women into the physical sciences is 39%, whereas in computer science it is only 19%. We also need to change how we develop and talk about women’s scientific careers. Many women still feel that they need to choose between having children and succeeding in their career.

If there was more gender equality with regards to salary, there would be more shared parental care.

Q: What is your current area of research?

A: I’m a cognitive neuropsychologist managing scientific research across several multi-disciplinary projects, as well as being senior data manager for Dementias Platform UK (DPUK). Dementia is our most pressing public health crisis: around 50 million people worldwide have dementia, and the WHO projects that number to treble by 2050. We haven’t yet found a cure, and I’m as driven and excited as I’ve ever been about preventing or delaying the onset of this disease.

My interests include using statistical modelling techniques to make sense of data arising from psychometric tests, and to explore the presence of two or more conditions or states in an individual – such as cognitive change and poor mental health, or childhood adversity and adult low mood.

DPUK’s Data Portal is a repository of more than 40 cohorts – long-term health studies – comprising data on more than 3 million participants from among members of the public. This data is hugely valuable, and it’s available for analysis by researchers with the aim of finding new insights into the causes, early diagnosis and treatment of dementia.

I have only ever wanted to be a scientist, over any other career.

Q: What does being a scientist mean to you?

A: I’ve always been curious about the mechanisms of the brain and body, ever since buying and avidly studying a Reader’s Digest book called How the Body Works when I was nine. That passion has never left me, and I’ve never let anything distract me from that – even after a long break to have my children.

Now that I’m working for Dementias Platform UK, I feel driven to contribute towards the search for ways to predict dementia before it is clinically evident, driving forward the search for interventions and a cure.

Q: Based on your own experience, what would be your message to girls and young women considering a career in science?

A: Science doesn’t stand still, but taking time out to have a family doesn’t need to be perceived as ‘the end’: there are many ways to stay abreast of findings, utilise institutional facilities for childcare, arrange working from home, or share childcare with partners, friends and family. There are always ways to pursue a career in science, if you really want to.

Listeners to Radio 4's Today Programme will have heard Eamonn O'Keeffe, a doctoral student in the Faculty of History, explaining a new discovery this morninig.

He found an 1810 diary entry by Matthew Tomlinson, a Yorkshire farmer, which suggests that recognisably modern understandings of homosexuality were being discussed by ordinary people earlier than is commonly thought.

Interestingly, this is not what Eamonn was looking for when he opened the large volume of diaries in Wakefield Library last year. In a guest post on Arts Blog, Eamonn takes us behind the scenes of his unusual find:

"While looking for something completely different, I discovered a remarkable discussion of homosexuality in the diary of an early-nineteenth-century Yorkshire farmer.

Reflecting on reports of the recent execution of a naval surgeon for sodomy, Matthew Tomlinson wrote on 14 January 1810: “it appears a paradox to me, how men, who are men, shou'd possess such a passion; and more particularly so, if it is their nature from childhood (as I am informed it is) – If they feel such an inclination, and propensity, at that certain time of life when youth genders [i.e. develops] into manhood; it must then be considered as natural otherwise, as a defect in nature”. Either way, “it seems cruel to punish that defect with death.” This inference sparked solemn religious introspection, as Tomlinson struggled to understand how a just Creator could countenance such severe penalties for a God-given trait: "It must seem strange indeed that God Almighty shou'd make a being, with such a nature; or such a defect in nature; and at the same time make a decree that if that being whome he had formed, shou'd at any time follow the dictates of that Nature with which he was formed he shou'd be punished with death."

A forty-five-year-old tenant farmer, Matthew Tomlinson resided at Dog House Farm on the Lupset Hall estate, a mile south-west of Wakefield in Yorkshire. His voluminous diaries chronicle local Luddite disturbances, agricultural life, and his attempts to find a second soulmate after the demise of his first wife. A former Methodist, Tomlinson was an observant but ecumenical Christian; he wrote extensively on faith, love, death, and the political and economic affairs of his day. Although a few historians have quoted from Tomlinson’s diaries in the past, his meditations on homosexuality have never previously been brought to light.

I identified the passage by chance in the course of my PhD research on British military musicians during the Napoleonic Wars. Returning by train from a conference in Leeds, I decided to stop in Wakefield on a whim to view Tomlinson’s diaries, having noticed colourful quotations from them in a book by Ellen Gibson Wilson on the Yorkshire election of 1807. As it turned out, the diaries had little to say about military music – Tomlinson was disdainful of patriotic pageantry – but his reflections on homosexuality, which I spotted by chance while paging through the journals, stood out to me as striking and unusual for the time. I decided to reach out to specialists on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sexuality to discern if my instincts were correct. Dr Rictor Norton and Prof Fara Dabhoiwala both generously shared their expertise, confirming the rarity and significance of my discovery.

The argument that same-sex relations were natural and innocuous was occasionally advanced in eighteenth-century England, while Enlightenment thinking on individual liberties and legal reform spurred calls for Britain to emulate its Continental counterparts by abolishing the death penalty for homosexual acts. Some Georgian men and women who engaged in same-sex relationships viewed their sexual orientation as innate: Halifax landowner Anne Lister justified her lesbian feelings as “natural” and “instinctive” in her diary in 1823. Utilitarian philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham even expressed support for the decriminalization of homosexuality in various writings from the 1770s to the 1820s, contending that sodomy statutes stemmed from “no other foundation than prejudice”. However, he did not dare publish such radical views. After all, this was an era when spreading false allegations of same-sex proclivities was considered by some commentators as akin to committing murder, such was the reputational ruin faced by the accused. In an age of rampant persecution, homosexual men in Georgian Britain were regularly executed or publicly disgraced, brutalized by hostile crowds in public pillories and forced into exile overseas. Tomlinson’s own meditations appear in his private diary, an intimate record of his thoughts not intended for a wider audience.

While Tomlinson’s writings reflect the opinions of only one man, the phrasing implies that his comments were informed by the views of others. This exciting new evidence complicates and enriches our understanding of historical attitudes towards sexuality, suggesting that the revolutionary conception of same-sex attraction as a natural human tendency, discernible from adolescence and deserving of acceptance, was mooted within the social circles of a Yorkshire farmer during the reign of George III.

Tomlinson’s reflections were prompted by reports of the court-martial and execution of naval surgeon James Nehemiah Taylor, who was hanged from the yard-arm of HMS Jamaica on 26 December 1809 for committing sodomy with his young servant. Newspapers across Britain and Ireland published accounts of the case, reminding their burgeoning readerships of the draconian state penalties for homosexual behaviour. Contemporary media reporting on sodomy cases, often couched in the language of moral panic, both reflected and reinforced social stigma against same-sex intimacy, but Tomlinson’s writings suggests that not all readers uncritically accepted the homophobic assumptions they encountered in the press. Disheartened by the ignominious demise of an accomplished medical man, the diarist questioned the justice of Taylor’s punishment and debated whether so-called “unnatural” acts were truly deserving of such an appellation.

However, Tomlinson’s musings are still very much the product of his time. Although the diarist seriously considered the proposition that sexual orientation was innate, he did not unequivocally endorse it. Erroneously believing homosexual behaviour was unknown among animals, Tomlinson still allowed for the possibility that homosexuality might be a choice and therefore (in his view) deserving of punishment, suggesting that capital sentences for sodomy be replaced by the still-gruesome alternative of castration.

Tomlinson’s meditations thus prove ultimately inconclusive, but nonetheless provide rare and historically valuable insight into the efforts of an ordinary person of faith to grapple with questions of sexual ethics more than two centuries ago. His comments anticipate many of the arguments deployed successfully by the LGBT+ and marriage equality movements in recent decades to promote acceptance of sexual diversity. Tomlinson’s remarkable reflections suggest that recognizably modern conceptions of human sexuality were circulating in British society more widely – and at an earlier date – than commonly assumed.

I am thrilled to be able to share this exciting and historically significant new evidence with a wider audience, particularly during LGBT+ History Month. I hope the buzz surrounding the find will inspire other historians and students to engage more fully with the rich collections available in local and regional archives, while serving as a reminder of the serendipity inherent in historical research. Sometimes the most interesting and important discoveries are the ones you weren’t even looking for!"

This post was written by Eamonn O'Keeffe, a historian in the Faculty of History at the University of Oxford.

By Guillermo Navalon

Darwin’s finches are among the most celebrated examples of adaptive radiation in the evolution of modern vertebrates and their study has been relevant since the journeys of the HMS Beagle in the eighteenth century which catalysed some of the first ideas about natural selection in the mind of a young Charles Darwin.

Despite many years of study which have led to a detailed understanding of the biology of these perching birds, including impressive decades-long studies in natural populations, there are still unanswered questions. Specifically, the factors explaining why this particular group of birds evolved to be much more diverse in species and shapes than other birds evolving alongside them in Galapagos and Cocos islands have remained largely unknown.

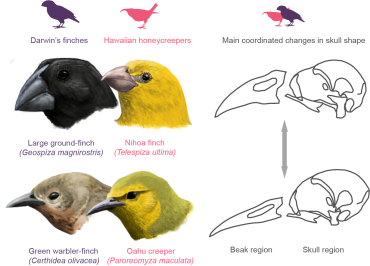

finch figure

finch figureAn international team of researchers from the UK and Spain tackled the question of why the rapid evolution in these birds from a different perspective. We showed in their study published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution that one of the key factors related to the evolutionary success of Darwin’s finches and Hawaiian honeycreepers might lie in how their beaks and skulls evolved.

Previous studies have demonstrated a tight link between the shapes and sizes of the beak and the feeding habits in both groups, which suggests that adaptation by natural selection to the different feeding resources available at the islands may have been one of the main processes driving their explosive evolution. Furthermore, changes in beak size and shape have been observed in natural populations of Darwin’s finches as a response to variations in feeding resources, strengthening these views.

However, recent studies on other groups of birds, some of which stem from the previous recent research of the team, have suggested that this strong match between beak and cranial morphology and ecology might not be pervasive in all birds.

By taking a broad scale, numerical approach at more than 400 species of landbirds (the group that encompasses all perching birds and many other lineages such as parrots, kingfishers, hornbills, eagles, vultures, owls and many others) we found that the beaks of Darwin’s finches and Hawaiian honeycreepers evolved in a stronger association with the rest of the skull than in most of the other lineages of landbirds. In other words, in these groups the beak is less independent in evolutionary terms than in most other landbirds.

Many questions remain: for instance, are these evolutionary situations isolated phenomena in these two archipelagos or have those been more common in the evolution of island or continental bird communities? Do these patterns characterise other adaptive radiations in birds?

Future research will likely solve at least some of these mysteries, bringing us one step closer to understanding better the evolution of the wonderful diversity of shapes in birds.

Guillermo Navalón is lead author of the study and a Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Oxford's Department of Earth Sciences, having recently graduated from a PhD at the University of Bristol.

Read the full study 'The consequences of craniofacial integration for the adaptive radiations of Darwin’s finches and Hawaiian honeycreepers' in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Professor Jonathan Herring’s new book, Law and the Relational Self, imagines how we could create laws that foster caring relationships, instead of breaking them apart.

Professor Herring is not your average law professor. His background is typical: studied Law at Hertford College, trained as a solicitor, did his BCL, then later went into education. But it’s not every solicitor or professor who ends up specialising in relationships.

He wrote a book called How to Argue, which was featured in newspapers as a guide to navigating those tricky conflicts in relationships. Late last year he hit the papers again, referenced as an argument expert in pieces about discussing Brexit and how to avoid doing the same at Christmas.

(He also gave a very entertaining talk on Can Law Be Fun, which is worth your time once you’ve finished reading this.)

He’s also written some more classic law texts, including Criminal Law: Texts, Cases and Materials and Family Law.

His most recent book almost seems to mix these two areas, looking at how law could move from protecting individual rights, to protecting and nurturing relationships.

Perhaps the first thing to consider when we look at this new book is what exactly is meant by ‘relational self’. Professor Herring elaborates: ‘The standard view of the self is individual. Our bodies, beliefs, jobs and possessions define who we are. The relational understanding instead argues that our identities emerge from our relationships.’

It’s a bit like the old John Donne quote “No man is an island”. We’re all part of a larger whole, and the things that make us us are the things or people that we care about. If we try to define ourselves separate to that, then we come up short.

He continues: ‘If you are ask a person to describe themselves, then they are likely to use relational terms: they are someone's sister; they belong to this religious group; or they support this football team. The things that give our life meaning are not things that are unique to us, but our relationships.’

Well, what does this mean for the law? Professor Herring explains that the standard model of law is currently about individual rights: ‘For many lawyers, the most important legal rights are those of autonomy, bodily integrity and privacy. But these rights are about keeping people away from you. They are about preserving the individual as separate from others.’

The law, as it stands, protects independence. It sees your rights as something to be protected from other people. You use the law to look after your interests, perhaps at the expense of others. Law and the Relational Self argues for a version of the law that looks at what’s best for people together.

‘A good law will be one that promotes caring relationships between people.’ He explains. ‘So a successful society, I argue, is not one where people are left free to pursue their own goals as "billiard balls in suits". Rather, it’s one where there are flourishing caring relationships.’

He cites law relating to children as a good example of this. The law currently enshrines the welfare of the child alone as the criteria by which judges should make decisions. This sounds sensible enough until you think about the relationships at play. If what seems best for a child isn’t best for their relationship with their caregiver, it actually isn’t going to be very good for the child after all.

We imagine we can think about the interests of children as separate from their parents, but that is a fiction … It would be better to ask what order will promote good caring relationships between the child and their carers.’

Or we can look at contract law. Effectively, it sets up an “us vs them”, with little obligation to consider what is fair for ‘them’. Whereas Jonathan argues that ‘a contract law designed to promote caring relationship would put obligations on contracting parties to look out for each other.’

A lot of the ideas in the book are informed by his previous work, but it was becoming a parent that crystalised all those ideas into the concept for Law and the Relational Self. Not, as you might expect, because of how a child requires care of its relationships to thrive (that one was a given). Instead, what struck him was how much emotional support children give to their parents.

He describes the experience, saying: ‘Parenthood vividly showed me how false vision the ideal of the "autonomous self-determining free man" is. That seems to be the dream that the law seeks to preserve, but to me it now looks like a nightmare. All the things in my life that give me joy are things that undermine my autonomy. But those are all good things. And I think is true for most people.’

This vulnerability is at the core of the book. We define ourselves by our relationships, and our relationships make us vulnerable, so it follows that…

‘Being vulnerable is an essential characteristic of being human. We might think that as adults we are able to "look after ourselves", but we rely on farmers and shops for food. We rely on friends for meaning and our mental health. We need a whole array of people, from doctors to sewerage workers, to maintain our wellbeing.

‘The strange thing is that society often presents it as a bad thing to be vulnerable and to need care. Carers are some of the most undervalued workers in our economy, when they should be celebrated.’

Professor Herring also highlights how that vulnerability means we sometimes need support from the law when something goes wrong: ‘The importance of care also shows how harmful abuse within an intimate relationship is. If intimate relationships define who we are and, indeed, are key to our survival, then abuse with in them is a "crime against the soul." One of the great strengths of relational theories is that it can highlight the particular evils of domestic abuse.’

A lot of what he says about the book seems to be a question of how the law reflects what we value. To change the focus of the law, would thus give us better building blocks to support a society of caring relationships.

What would such a legal system look like and what would it say about our values? Professor Herring says: ‘At the moment, whether one listens to debates about the impact of Brexit or the arguments among politicians, it would be thought that economic productivity is the mark of a successful society.

‘But what if our schooling, our labour market, our health care system, our political decisions were shaped around asking ‘what will promote good caring relationships?’ This would have huge ramifications for employment practices, tax systems, benefits payments. Being a carer would be an accepted part of being a citizen. The legal and political system would be built around that as a norm rather than, as it is at the moment, being seen as a problem if a worker is a carer.’

In the end, Law and the Relational Self is a book about what we decide important and how we reinforce that. It should be a great read for anyone with in interest in law and how it shapes us.

Jonathan sums it up by saying: ‘We know that making money is not what is important in life. We know our lives are not just "ours" to live as we like, but are made up of responsibilities which constrain our freedom, but that we choose because they are of huge importance and value. We know that what is important is our interactions with others, the smile, the touch, the kiss, the giggle together. That is what matters, not the high sounds principles of autonomy and freedom which dominate the law.’

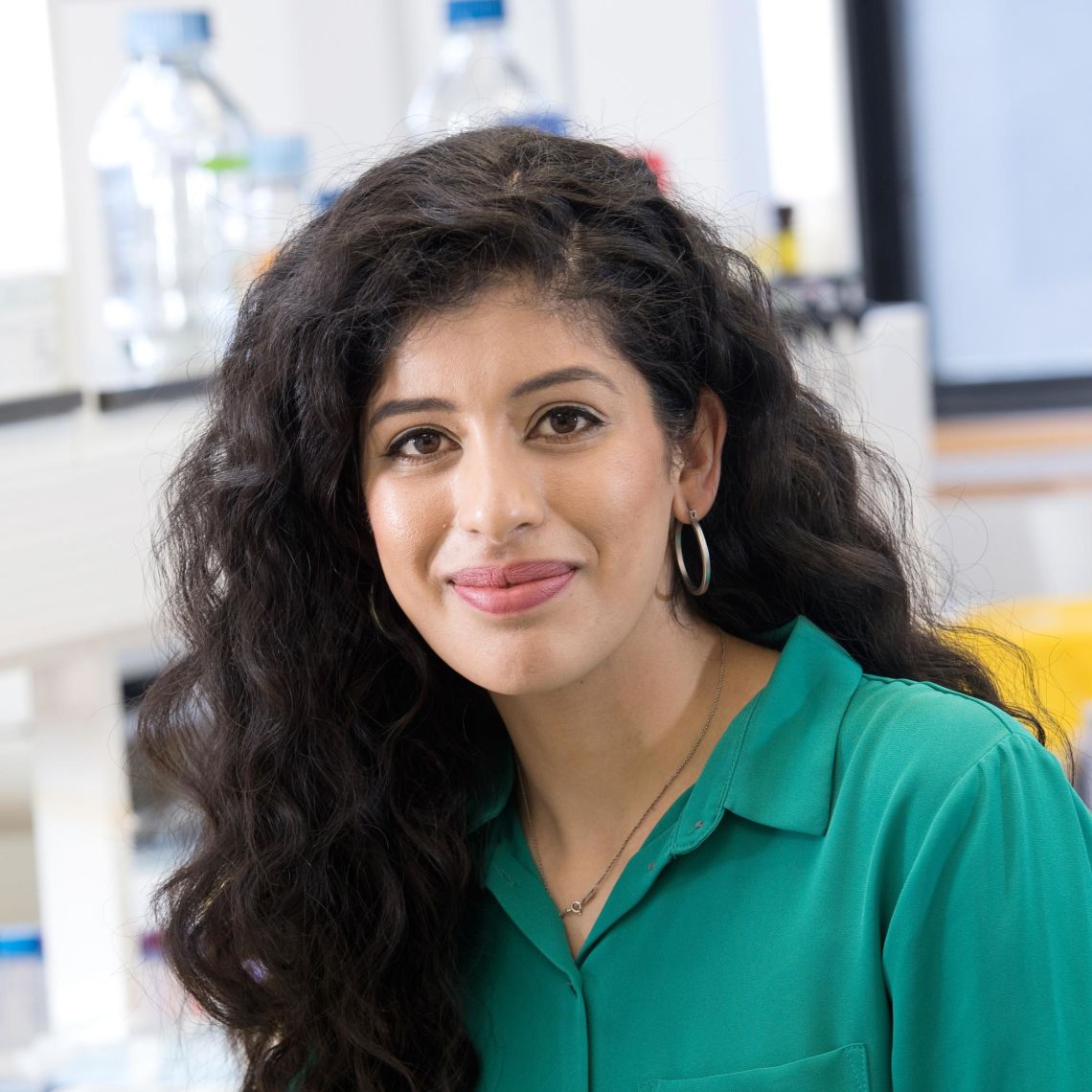

The latest in our ScienceBlog series of 'amazing people at Oxford you should know about' is Dr Pavandeep Rai. A Post-doctoral Research Scientist in the Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, her work focuses on the effect of something called 'mitochondria' on Parkinson's disease, using cutting edge gene-editing cool CRISPR-Cas. Here she guides us through her career and experiences of pushing the boundaries of science in both research and art...

To start with, can you give us a beginner’s guide to your research? What is ‘mitochondria drug discovery’?

I started my ‘love affair’ with mitochondria during my undergrad degree at Birmingham, particularly in my year in industry with AstraZeneca. Basically, mitochondria are organelles, small entities within our cells. Their main job is to make something called ATP, which is the energy our cells use. So, if something goes wrong or your mitochondria start to degrade, then that will reduce the amount of energy and your cells don’t work as well.

The lab I’m working in looks specifically at Parkinson’s disease. By looking at the mitochondria, we can try to find ways to improve their functionality. Can we stop them from degrading? Once they’ve started, can we stop them from getting worse?

Currently, I’m using genetic editing tool called CRISPR-Cas. It’s been in the news recently, you might have seen those stories about ‘designer babies’ and the like? But we use it as a research tool to see how removing genes from the genome affects mitochondria.

If we remove a gene and it improves function, then we could maybe use it as a treatment for Parkinson’s.

If removing a gene decreases function in healthy cells, then that tells us something else. Perhaps this is one of the ways that the disease itself progresses?

So, it ties into two aspects of research: one is treatment and the other is understanding.

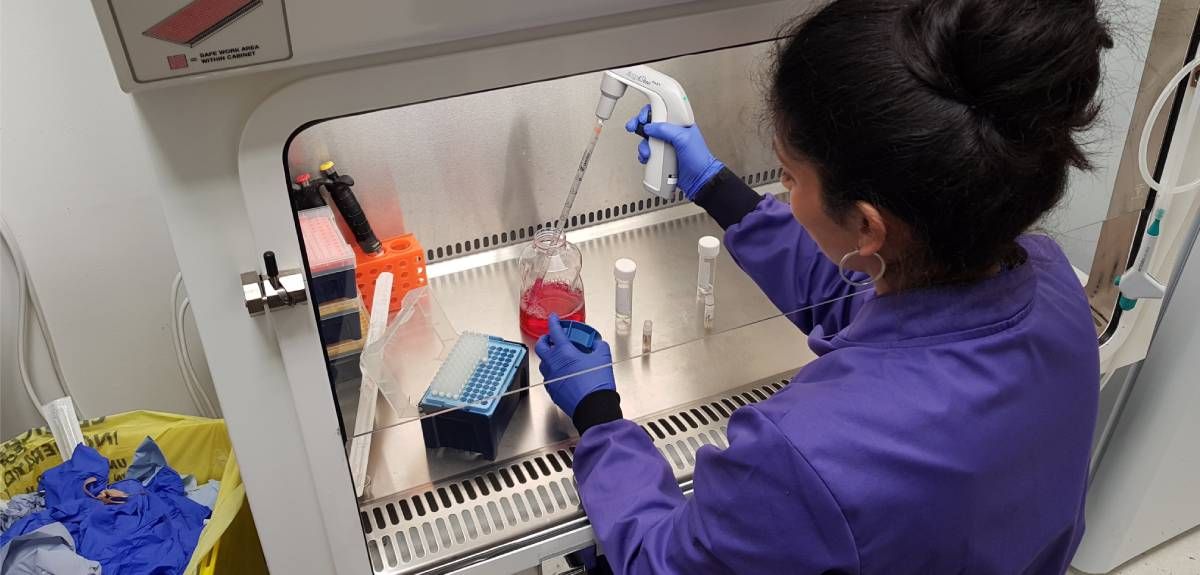

How’s it been so far to use CRISPR-Cas and the general discourse around that?

It’s one of the most innovative areas at the moment. We’re seeing huge advances. Previously, we were only able to completely physically remove genes. Now, we can ‘silence’ genes by turning them off temporarily. This means we can do a kind of ‘before and after’; what happens when we turn the gene off? And what happens when we turn it back on again?

The technology is getting more specific and detailed all the time, too. I think it’s going to become a really huge therapeutic area in future.

For example, there are clinical trials being run into diseases like Sickle Cell. With diseases like that, where you have one specific gene that’s ‘switched wrongly’, you could eventually use it to just flip the switch the right way.

Meanwhile, for Parkinson’s, we’re using it more as a tool to look for helpful molecules for treatment.

Any thoughts on that wider discourse around gene editing?

In the research community, it is very much a tool for research and very specific treatments. That said, people will always use tools for things they aren’t designed for.

When I was at Newcastle, they were working on mitochondrial donation or ‘three parent baby’ research to treat mitochondria disease patients. It’s tightly regulated here. But in other places around the world, it’s being used to treat women with low fertility, or to treat other diseases.

Like any tool, you create it for the general good. Then you have to keep facing those ethical and moral issues in the future. I recently went to a conference in the US, which highlighted these issues. So that’s one way for the research community to ask important questions about guidelines and regulation.

To you, what’s the most exciting thing about the work you’re doing?

For me, it’s using CRISPR-Cas to really understand disease. There are still so many questions that need to be answered and these tools are advancing our understanding massively. Every other month there’s news about new genes and pathways.

And I think the work of the Oxford Parkinson’s Disease Centre (OPDC) is really important, especially because of its excellent collaboration with patients. We have a lot of cell lines available to us, and using these stem cells we can grow them to form neurons. Working on actual neuronal tissue makes a huge difference for modelling the complexity of the disease. Along with the new techniques of CRISPR, that puts the OPDC in a leading position world-wide.

What are the big benefits of patient involvement and contribution?

There’s a huge impact! One of the reasons a lot of companies like to work with research institutions in the UK is that our research is tied to institutions like the NHS. There’s a great referrals system to get patients together and get them organised. And the patients just really want to help us and to see progress in therapy development.

There’s fundraising too, not just for the big charities, but also from local patient groups. They have things like a pub quiz to help raise money so we can buy lab equipment.

They also donate stem cells, do clinical trials and make samples available to us, which helps with diagnosis. Their families offer support too! It’s an awful disease, but it’s a powerful community.

What are some things about working in research and science that surprised you or might surprise others?

The more you research something, the more questions arise. That surprises me.

I think there’s this perception of scientists as people who have all the answers, but actually we just have all the questions! It’s all about asking the right questions and finding out how to answer them, rather than finding the answers themselves.

You’ve worked in Newcastle, Birmingham, and now Oxford. What have been your favourite things about those places?

I’m originally from Kenya and when we first moved from there, we had family in Birmingham. So, I went to nursery in Birmingham and still have family there, so I’ve always had a soft spot for it. I’m a midlands girl at heart, and now I live in Leamington Spa (which is a much trendier place now than the small town I grew up in).

When I did my year in industry, I lived in Manchester. I loved the north! And I made great links with a community of scientists who were also on the placement programme with my at AstraZeneca.

Then I moved to Newcastle for my masters and PhD. It has a great quality of life; you’re near the coast, near 3 national parks, and you can walk everywhere. Plus great food and nightlife, so definitely a ‘work hard, play hard’ PhD. My PhD mentor was also very knowledgeable, he was a clinician neurologist, so he really drove home the patient focussed aspect of research.

Then I saw this post-doc in Oxford with Richard Wade-Martins. It was in the area of drug discovery, which is a great fit. Plus, it’s a great lab with amazing resources and research, and the people here push you to be at the forefront of new techniques. So, all of that drew me to Oxford. And then I arrived and thought ‘Oh, Oxford’s so nice!’

You mentioned your PhD mentor was a pretty big influence – were there any other people or events that inspired you and shaped your work?

My year in industry was also really formative, finding out what commercial research looks like. I also worked at the Novartis Institute of Biomedical Research in Basel, Switzerland during my PhD, where my collaborator was keen to give me experience of all the different stuff going on there. Commercial science is very goal-oriented, so you get these huge institutions working together really well to get results to for compounds and allow products to be delivered to the market.

I’m beginning to explore the idea of business in my research too, like a start-up or spinout. Oxford is a great enterprising hub, with lots of support like Enterprising Oxford. I’m part of a cohort called RisingWISE, which helps 40 women from Oxford and Cambridge develop creative, innovative, enterprising skills. It’s also great for meeting women from industry, gaining mentorship and networking

I’ve recently also been accepted onto the Ideas 2 Impact programme at the Säid Business School. This initiative recruits Postdocs to join the Strategy and Innovation module of the MBA programme, giving Scientist and Executives the opportunity to work together on business ideas. I am really looking forward to starting this in January.

Any ideas sparked for a spinout already?

I’d love to have one, but not yet! At the moment for me, it’s about building that skillset and that mind-set to think about research in that commercial way. As a researcher we’re already analytical, and setting up research groups or labs is already a bit of an entrepreneurial prospect. But you also need to flex those creative muscles.

Are there any other difference between academia and industry, or things they can learn from each other, that it’s important to highlight?

I’ve always seemed to be part of collaborations between the two, which I think are becoming more and more normal. They have this really good balance between them. At the end of the day, industries are keen to make their bottom line, to find a compound or therapy that will cure a disease but also make a profit. Academia is more about the minutia, going back to basics and saying ‘okay, what does this protein do?’ rather than jumping to ‘what could it cure?’

And sometimes maybe academia gets a little stuck in its rut? It can be too focused and detailed-oriented, with researchers hidden away in our laboratories. And I think industry can sometimes be not detailed enough, as they’ve got deadlines and money and time constraints.

So these collaborations are a really good middle ground. They help researchers be part of something bigger and impact-focused, but gives industry the ability to really understand therapies. And this makes for better drugs!

Any other moments in your career you’re proud of and want to celebrate?

I think handing in my thesis for my PhD, probably! That was tough!

I have loads of small things I’m proud of – I’m proud of supervising students and seeing them flourish. I’ve supervised a lot of medics who’ve come in with no experience of holding a pipette, and by the end of things they were giving me ideas for their project and learning independently. So, I think training is a really important aspect of science as it can go both ways.

And being part of collaborations that have meaningful impacts on patients! Having a career with a cause is important to me.

Can I ask about experience of being a woman and minority in science? What would you like to see put into place to encourage people into STEM?

As a woman, it’s interesting! There’s lots of women in science, especially biology, but less in other STEM areas. Why do so many of us go into biology? I reckon that has something to do with how we’re raised.

I think it’s retention that really suffers, across all subjects. I’d like to see us asking questions like: where are people dropping off? When are they changing careers? What are the barriers making it difficult? Is it the temporary nature of academic contacts? Do we need to rethink how we deal with childcare and maternity leave?

Being a woman of colour (I hate that phrasing, by the way, but it’s how it’s said), you don’t have many role models; not a lot of professors look like you. There’s a community aspect too; where do you feel like you belong? I’ve been in several situations across various jobs where I’ve been the only woman and person of colour in the room. I never really thought to question it until recently.

I don’t think addressing that is a quota-filling task. I think it’s about going into communities and starting with the grassroots. Where are we employing people from? How do we expand to recruit from new communities, schools and universities across the country and world?

Also, I think unconscious bias has a huge part to play. In this country, it seems like some people think that when you don’t see overt racism, then it doesn’t exist. I think it’s more subtle and more nuanced, which makes it hard to challenge. We all have biases we don’t think about, so that kind of introspection is really important.

What is one really interesting thing that you’d like everyone to know?

I’d like people to know how close connections are related to healthy longevity.

Aside from exercise, good meaningful relationships are the best thing for long-term health. So go and make connections, volunteer, enjoy your hobbies and just make time to meet like-minded people. Friendship – it really is the key to a long and healthy life.

If you could work with any scientist, living or dead, who would you want to work with?

The scientist I would most loved to have met is Wangari Maathi. She was born in Kenya (as was I, so very close my heart) and after winning a scholarship to study biology in the US, she was the first woman in Central and East Africa to gain a doctorate. She recognized that deforestation was causing a decrease in biodiversity and food crops, affecting mainly women who are the resource gatherers in many African communities. She founded the Green Belt Movement which paid local women to plant trees. The Movement grew to encompass almost a million people and had major political ramifications in Kenya.

In 1990 she set up her own political party and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004.

I think Dr Maathi’s ability to apply her science to a grass roots problem and make rapid impact in improving the lives of people in her community is incredibly aspiring. I would love to be able to do similar work in the future, using my background in biological research to bring about positive changes in healthcare for individuals.

You’ve also done some really interesting outreach work in the past, right? Can you tell me about that?

Yes, I have a longstanding interest in getting scientists out of their labs and involved in other areas and in communities.

In Newcastle, we had a collaboration with a Fine Art course, creating installations that drew on all kinds of science themes. We then went on to work with the National Trust’s Women in STEM project, with award-winning artist Olivia Turner. We created these amazing 6-foot wooden sculptures that are now on display in the Cheeseburn Sculpture Park.

I’m very keen to re-establish that kind of project in Oxford, too! I’m meeting and liaising with various groups, so watch this space.

- ‹ previous

- 44 of 248

- next ›

Teaching the World’s Future Leaders

Teaching the World’s Future Leaders  A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future

A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance

Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance

The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance  The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham

The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham  Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year

Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage