Features

We may not have found life on Mars, but there is considerable excitement in the Oxford scientific community about the imminent possibility of detecting the landing of NASA’s Perseverance Rover using InSight, another spacecraft which is already on the red planet.

University physicists believe that, for the first time, they might be able to ‘hear’ a spacecraft land on Mars, when Perseverance arrives at Earth’s ‘near’ neighbour in about a month’s time around 18 February.

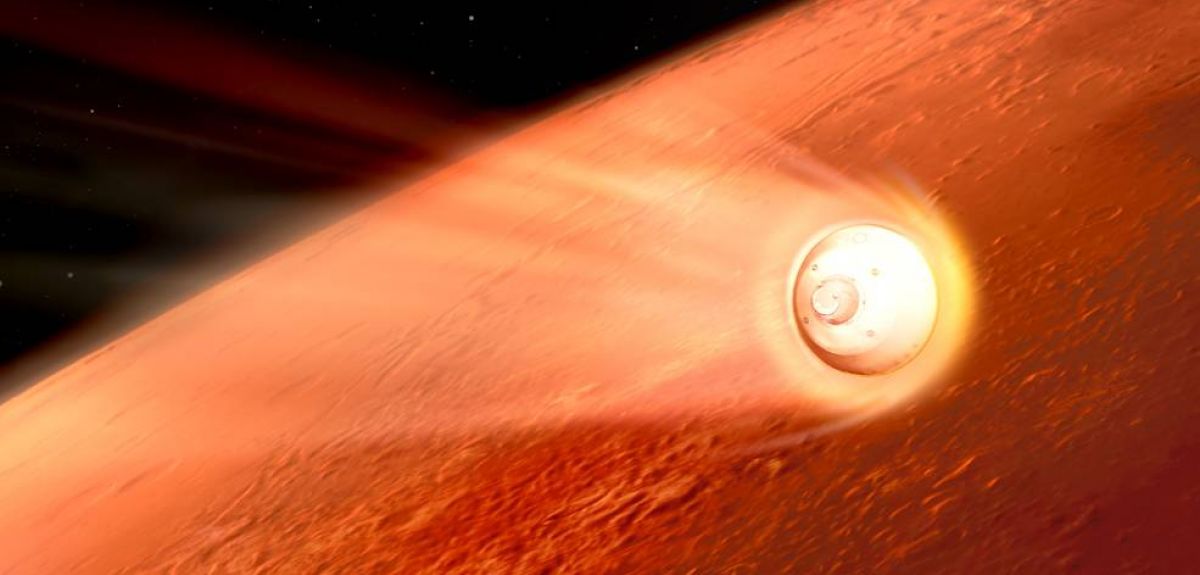

And NASA’s new probe is certainly not arriving quietly. The unmanned craft will plunge through the Martian atmosphere at enormous speeds, accompanied by a sonic boom created by its rapid deceleration. At the point it enters the atmosphere, it will be travelling at more than 15,000 km/h and its heat shield will reach more than 1,300 degrees centigrade during the descent.

NASA’s new probe is certainly not arriving quietly. The unmanned craft will plunge through the Martian atmosphere at enormous speeds, accompanied by a sonic boom created by its rapid deceleration

It will deploy two large balance masses which will hit the ground at hypersonic speeds, crashing down at a speed of 4,000 metres per second. It is these two masses which the scientists are hoping will create detectable seismic waves - which will travel the 3,452 kilometres between Perseverance’s landing site and InSight’s location.

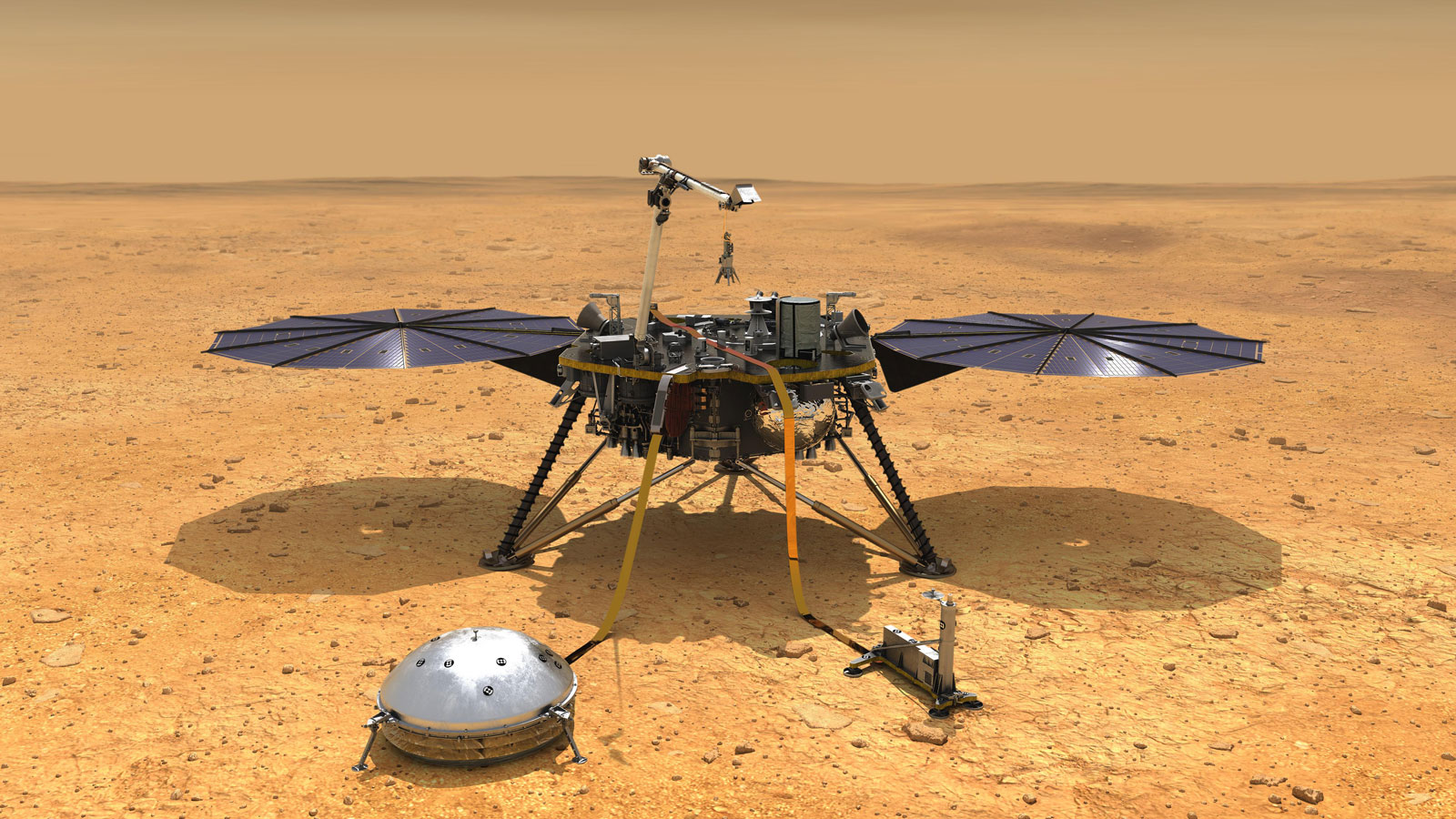

The ears to ‘hear’ the impact are the InSight probe, which was sent to Mars three years ago to listen for seismic activity and impacts from meteorites. Parts of the spacecraft were built at Imperial College London and tested in the Department of Physics at the University of Oxford.

InSight detects seismic activity (marsquakes) to help scientists understand better the interior structure of Mars. Although many hundreds of marsquakes have been detected since InSight’s landing in 2018, no impact events (meteorites hitting the surface and producing seismic waves) have been detected. Impact events are of particular interest because they can be constrained in timing and location from pictures taken by orbiting satellites, and thus used to ‘calibrate’ seismic measurements.

So, the arrival of Perseverance Rover potentially offers the first opportunity to detect a known, planned landing of a foreign body on the surface of the planet. It could provide a wealth of evidence on the structure and atmosphere of Mars and has got the scientific community very excited about its potential.

According to Oxford physicist, Ben Fernando, a member of the InSight team, ‘This is an incredibly exciting experiment. This is the first time that this has ever been tried on another planet, so we’re very much looking forward to seeing how it turns out.’

This is the first time that this has ever been tried on another planet, so we’re very much looking forward to seeing how it turns out

InSight team member, Ben Fernando

InSight’s seismometers are potentially sensitive enough to detect Perseverance’s landing, even though this is expected to be very challenging - given the significant distance between the two landing sites. It is around the same distance as from London to Cairo. Nevertheless, the Oxford team believes the impact could potentially be detected by InSight and thus provide an immensely useful ‘calibration’.

According to Ben Fernando, ‘This would be the first event detected on Mars by InSight with a known temporal and spatial localisation. If we do detect it, it will enable us exactly to constrain the speed at which seismic waves propagate between Perseverance and InSight.’

A newly-published paper from the InSight team states, ‘Perseverance’s landing is targeted for approximately 15:00 Local True Solar Time (LTST) on February 18, 2021 (this is 20:00 UTC/GMT on Earth).’

The paper continues, ‘The spacecraft will generate a sonic boom during descent, from the time at which the atmosphere is dense enough for substantial compression to occur (altitudes around 100 km and below), until the spacecraft’s speed becomes sub-sonic, just under three minutes prior to touchdown. This sonic boom will rapidly decay into a linear acoustic wave, with some of its energy striking the surface and undergoing seismo-acoustic conversion into elasto-dynamic seismic waves, whilst some energy remains in the atmosphere and propagates as infrasonic pressure waves.’

The paper concludes, ‘We identified three possible sources of seismo-acoustic signals generated by the EDL (entry, descent, landing) sequence of the Perseverance lander: (1 ) the propagation of acoustic waves in the atmosphere formed by the decay of the Mach shock, (2) the seismo-acoustic air-to-ground coupling of these waves inducing signals in the solid ground, and the elasto-dynamic seismic waves propagating in the ground from the hypersonic impact of the CMBDs.’

InSight will ‘listen’ for the acoustic signal of the sonic boom in the atmosphere. But scientists think the best chance of detecting the landing will be the seismic impact of the balance masses.

The team expects to receive data from InSight within a day or two of Perseverance’s landing, after which they will investigate whether they have made a successful detection.

Short explanatory video: http://bit.ly/insight-m2020-video

Instagram film: https://www.instagram.com/tv/CJvxmSaokd3/

COVID-19 has asked a lot of everyone. At the national level, decisions have been taken that affect everything from people’s movements to the running of businesses. For many, there are also individual decisions in which personal risks are weighed: Should I venture to my local grocery store, or should I shop online? Can I eat at the restaurant, or should I buy take out?

In many households, dinner time musings often drifted to something like the following: 'I have barely seen anyone in person for many weeks. I know my neighbours haven’t either. My favourite park is much emptier than usual and the community around me has made many sacrifices. Does this mean COVID-19 is actually decreasing in my area?'

While most people have a UK-wide view and newspapers report national statistics, the decisions that people make to help contain the pandemic are at an individual and personal level. The behaviour of people in Oxford has no sizable effect on COVID-19’s growth or decline in far away Scotland, and these decisions need real-time, local information, an up to date resource that anyone can access to see how their town or county is doing.

View Local Covid UK Map here: https://localcovid.info/

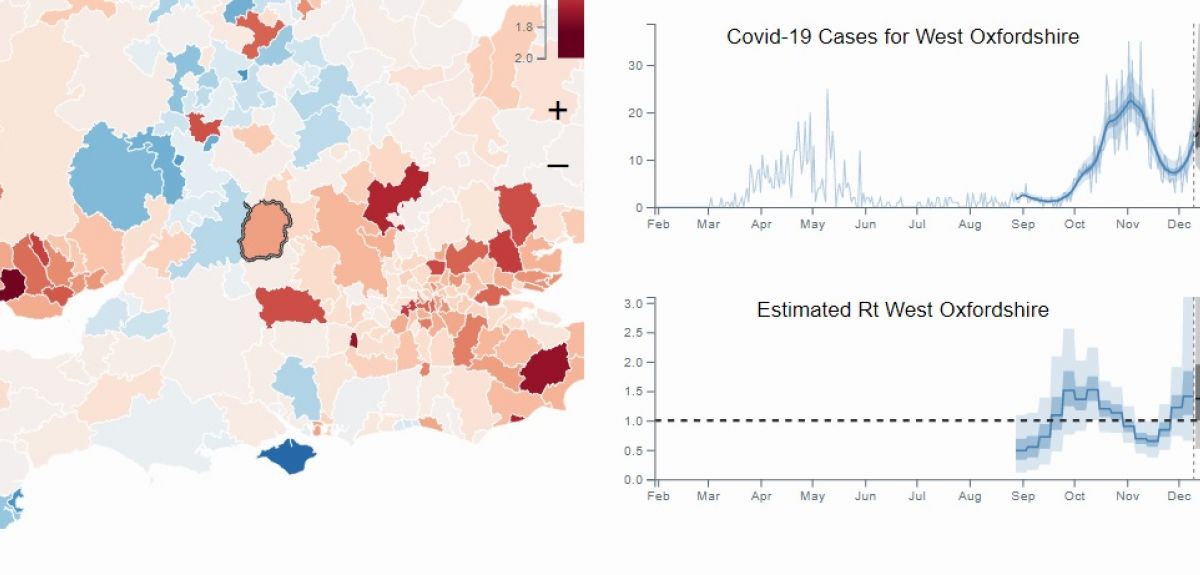

Using historical COVID-19 case counts, the map at localcovid.info shows an estimate for the R number in each local area, along with projections of how the epidemic might develop in the next two weeks

The reproduction number or “R number” tells us about the growth and decline of COVID-19. It is an estimate of the number of people that someone with COVID-19 will pass the virus on to. A reproduction number of R=2 means that an infected person is likely to transmit the virus on to two other people, each of whom then passes it to two more people, and the epidemic grows quickly. On the other hand, if R=1, then on average each infected person only infects one other person and the size of the epidemic remains roughly constant. A reproduction number of R<1 is good news: the number of new infections is reducing and over time the epidemic will shrink.

Yee Whye Teh, Professor of Statistical Machine Learning at the Department of Statistics, University of Oxford, explains how the national “R number” is made up of many local parts: 'The national R number describes an average transmission rate across the nation. It is an aggregate statistic made up of many smaller contributions, and belies significant variations in COVID-19 transmissions rates, both geographically as well as across different sections of society. In order to inform individual decisions, local information relevant to the individual is needed.'

Led by Professor Teh, a team from the Computational Statistics and Machine Learning research group at Oxford’s Department of Statistics has built a model that monitors the daily spread of the virus locally. Their results can be accessed online by anyone at localcovid.info, which gives an informative view of the rate of transmission of COVID-19 in areas such as Oxford, Cherwell, West Oxfordshire, Swindon and more than 300 other local authorities in the UK.

Using historical COVID-19 case counts, the map at localcovid.info shows an estimate for the R number in each local area, along with projections of how the epidemic might develop in the next two weeks. The estimates of R in the map contain what statisticians call “error bars” or “credible intervals”. These are there to say that no one knows the true R number in an area, but we are quite sure that we can pin it down to within a narrow band. For example, in the map snapshot December 14, we are 95% sure that R is currently between 0.7 and 1.4 in Oxford, with a median of 1.0, given the team’s statistical model and the data available.

The real work dynamics of epidemics are incredibly complicated.

Michael Hutchinson, a PhD student in professor Teh’s group, explains how the “R number” is estimated from data: 'This is a difficult task. The real work dynamics of epidemics are incredibly complicated. To begin estimating the R number we start by proposing a simplified statistical model of the real world which captures the most important aspects of the epidemic. We never observe the R number directly, we only observe positive COVID-19 cases. We know that the R number drives new infections however, so using the model and observations of numbers of cases we can infer what R is likely to be. Essentially, using what we see in the world, we reverse engineer what the unobservable R is.'

The statistical model underlying these estimates of R relies on publicly available Pillar 1+2 daily counts of positive PCR swab tests by specimen date, for 312 lower-tier local authorities in England, the 14 NHS Health Boards in Scotland and the 22 unitary local authorities in Wales. The model makes additional use of commuter flow data from the UK 2011 Census and population estimates, as COVID-19 spreads not just among the population of individual areas, but also across areas. As with many aspects of statistical epidemiology, these estimates of R need to be read with care, and in the context of other pieces of data that provide relevant information, e.g. data from the ZOE symptom tracker, seroprevalence studies, test positivity rates, as well as hospitalisation and death rates.

Dr. Ulrich Paquet, a research scientist seconded to the group, noted: 'We are pleasantly surprised to see how the estimates for R have dropped below one for a while in many areas, especially in the North where Tier 3 rules applied since October. We guess that we shouldn’t be surprised to see the result of public behaviour and national action show up so clearly in a model, but we still are! As statisticians, we love it when the data speaks for itself.'

Prof. Teh concluded on a more sombre note: 'We are concerned that since the lockdown was lifted in December, many areas, particularly in the Southeast and London, have seen cases continue to increase. We hope the tool we built at localcovid.info will be helpful to you, in making your decisions to stay safe and to help protect your loved ones.'

Track your local area on the Local Covid UK Map here: https://localcovid.info/.

Social distancing has become one of the key strategies for reducing COVID-19 transmission, together with mask wearing and contact tracing. However, a new study, published in the journal PLOS ONE, maintains it is possible to maximise the impact of social distancing on viral transmission and minimise its impact on the economy and people's well-being - by focusing on the people who are the main drivers of infection.

A new study, published today...maintains it is possible to maximise the impact of social distancing...and minimise its impact on the economy and people's well-being - by focusing on the people who are the main drivers of infection

Lockdowns are a very effective way to reduce transmission and may be necessary, when the infection rate has to be curtailed rapidly, for example because of very high case rates. But lockdowns are disruptive and, in the longer term, more sustainable methods could be adopted.

Today’s study differs in approach from many of the main epidemic models in that it focuses specifically on the role of individuals and, in particular, on the very wide variation seen in the behaviour of different people.

Some individuals interact at a much higher rate than others, because of their work, living conditions or social habits - increasing both their chances of being infected and the probability that they will infect others. The simple theoretical model presented in this paper shows that these people are not only the main drivers of infection, but also the key to controlling the epidemic.

This study shows that social distancing can be highly effective in controlling viral transmission. By reducing the interactions of the most interactive individuals, this can be done while maintaining significant levels of activity in the population as a whole.

Social distancing can be highly effective in controlling viral transmission. By reducing the interactions of the most interactive individuals, this can be done while maintaining significant levels of activity in the population as a whole

Professor Christopher Ramsey, the author of the study and a physicist specialising in interdisciplinary science in the School of Archaeology, says, ‘Until vaccination is widespread, we might have to consider that social interaction time is like exposure to the sun, very beneficial in limited amounts, but harmful in excess.’

Since, in many countries, workplaces have been made relatively COVID-secure, social interaction outside the household has come to play a dominant role in viral transmission. Completely stopping such interactions will work, as in a total lockdown, but is a drastic measure and needs to be time-limited.

Many countries have found that, once socialisation is allowed again, infection rates rise. The model in this paper suggests this is largely because of the high interaction rates of a minority of people, rather than the interaction rates in the population as a whole.

For countries trying to reopen society in a controlled way, a way forward would be to limit interaction rates for individuals. So, rather than simply allowing or forbidding mixing between households in homes and hospitality venues, it would be more effective to say how frequently this can be done safely.

When rates of infection are still moderate, it might be necessary to recommend socialising no more than once a week. As rates improve, this might be relaxed to once every three days, and then unrestricted when the infection rate is very low. This could provide much finer control over the interaction rates than opening and closing bars and restaurants, and it could enable economic activity and some socialisation for everyone most of the time.

This approach should work, if people comply, because someone who socialises every day, rather than just once a week, has seven times the chance of becoming infected and also seven times the probability of infecting someone else

This approach should work, if people comply, because someone who socialises every day, rather than just once a week, has seven times the chance of becoming infected and also seven times the probability of infecting someone else. This person’s potential to spread the virus is nearly 50 times higher!

For this reason, the model suggests, the key aim of social distancing policies should be to avoid a minority of individuals interacting far more than the average. Such an approach would also help contact-tracing, since relevant contacts would be fewer if social interactions were limited to once every few days and so more time could be spent following them up properly.

As widespread mask wearing, improvements in the weather and, ultimately, vaccination help contain the disease, the extent to which socialisation should be possible will gradually increase until we get back to a more normal situation. Ideally, this should be possible without multiple waves of infection and the associated extreme measures that might be needed to bring these under control. However, to do so will need us to focus on individual behaviour and when it comes to social interactions that also implies individual responsibility.

The pandemic is testing our societal structures like never before. To deal with it successfully, we need to think and act collectively, led by our key institutions. But at a time when unity is critical, are we about to see the effects of a long-standing and corrosive drip feed of mistrust?

The rapid development and testing of COVID-19 vaccines has been an extraordinary scientific undertaking. What happens now is arguably even more important: to ensure the vaccines are an effective intervention, people will need to take them. The practical challenges of manufacturing and dispensing millions of doses worldwide are of course immense, but societies also have to deal with the issue of vaccine hesitancy: the belief that a vaccine may be unnecessary, ineffective, or unsafe (and perhaps all three). Unsurprisingly, people who have these concerns may be reluctant to take a vaccine; they may even refuse it outright.

The pandemic has created the ideal conditions for mistrust of a COVID-19 vaccine to thrive. Part of the problem is the complexity and variability of transmission and infection.

Vaccine hesitancy isn’t new. However, the pandemic has created the ideal conditions for mistrust of a COVID-19 vaccine to thrive. Part of the problem is the complexity and variability of transmission and infection. The fact that you may not catch the virus if you break social distancing guidelines and that the illness may be mild if you do get it, has led some to conclude that there isn’t a real problem. The unprecedented speed with which the vaccines have been developed has also provoked worry: there are concerns that safety has been compromised or that the vaccine will be rolled out before we understand the extent and nature of possible side effects. Moreover, the Internet is awash with misinformation -- including conspiracy theories – about the virus, lockdown, and vaccinations.

Finally, it’s worth bearing in mind that this is all taking place after a long period in which trust in science, medicine, and key institutions has been steadily eroded. We can’t overcome the virus if health experts aren’t trusted; yet that’s exactly how many people have been primed to react.

In the Oxford Coronavirus Explanations, Attitudes, and Narratives Survey (OCEANS), we aimed to gauge the extent of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: how many people are sceptical about vaccination; whether particular sections of the population are especially reluctant; and, most importantly, why people are hesitant. 5,114 adults took part, representative of the UK population for age, gender, ethnicity, income, and region.

First, the good news: we found a substantial majority in favour of a COVID-19 vaccine, with 72% willing to be vaccinated. But this isn’t enough to be truly considered a consensus. 16% of the population are very unsure about receiving a COVID-19 vaccine, and another 12% are likely to delay or avoid getting the vaccine. One in twenty people describe themselves as anti-vaccination for COVID-19.

Vaccine hesitancy has implications for us all. The fewer the people who are vaccinated, the greater the number of people who will get seriously ill.

The signs are concerning: we may be close to a tipping point, when suspicion of vaccination becomes mainstream. Already we’ve seen conspiracy theories about the virus achieve significant traction. Is COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy about to follow in their wake?

In our survey, one in five people thought vaccine data are fabricated and another one in four people did not know whether such fraud is occurring. Why does this matter? Vaccine hesitancy has implications for us all. The fewer the people who are vaccinated, the greater the number of people who will get seriously ill. Also, we don’t yet know how many people will need to be vaccinated to achieve full herd immunity, but an estimate of 80% has been suggested. As things stand, our survey suggests that figure may not be easy to achieve.

The fear that vaccine hesitancy may be going mainstream is borne out by the fact that, in our survey, mistrust wasn’t confined to particular groups; on the contrary, it was evident across the population. Hesitancy was slightly higher in young people, women, those on lower income, and people of Black ethnicity, but the size of the associations was very small. So we can’t explain COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy by reference to socio-demographic factors.

What, then, lies behind these beliefs? Our survey suggests that what matters most is the way people think about a number of key issues relating to a COVID-19 vaccine, specifically:

• the potential collective benefit

• the likelihood of COVID-19 infection

• the effectiveness of a vaccine

• its side-effects

• the speed of vaccine development

So those who are hesitant about a COVID-19 vaccine tend to be people who may not be so aware of the public health aspects of a vaccine, don’t consider themselves at significant risk of illness, doubt the efficacy of a vaccine, worry about potential side effects, or fear that it’s been developed too quickly.

When I speak to people who are enthusiastic about vaccination the first thing they say is that it helps everyone. In contrast, people wary of a vaccine often focus on their own situation: they’ll tell me that they’re unlikely to fall ill, for example, or worry about what may go wrong if they were to take a vaccine. But this perspective can change: when I’ve asked vaccine-hesitant individuals to imagine that someone close to them is especially vulnerable to COVID-19 they say that they’re more likely to get vaccinated.

Our survey shows people want reassurance that safety hasn’t been sacrificed for speed. They want accurate and comprehensible guidance on effectiveness, potential risks, and how long protection will last. And they’re not scared of detail: messaging should provide us with the full picture.

Vaccine scepticism, it would seem, is linked to a wider crisis of trust. Our data suggest that people who are vaccine hesitant are more likely to be mistrustful of doctors, are more likely to hold conspiracy beliefs, and to have little or no faith in institutions. They can also feel like they are of lower social status compared to others. What we see here is a combination of vulnerability and distrust of those in authority. That manifests itself in defensiveness. Unwilling to be experimented upon by people who don’t care about their well-being, they avoid vaccination.

The next few months are vital. Messaging must be strong and clear: for the benefit of everyone, each of us has a duty to get vaccinated when possible. Most people can see vaccination as the light at the end of the tunnel, but they are also looking – perfectly reasonably – for information they can trust. Our survey shows they want reassurance that safety hasn’t been sacrificed for speed. They want accurate and comprehensible guidance on effectiveness, potential risks, and how long protection will last. And they’re not scared of detail: rather than slogans, soundbites, and selective emphases, messaging should provide us with the full picture.

It must also be energetic, proactive, and open-minded. Make no mistake: people who are vaccine hesitant are thinking long and hard about whether to take a COVID-19 vaccine. Public health professionals need to be out and about across the country, listening to concerns and responding transparently. Presenting accurate information as powerfully as possible is obviously essential, but we also need to counter, and limit the spread of, vaccine misinformation.

Over the longer term, we need to rebuild trust in public institutions and experts – a task that will require society to address the sense of marginalisation that has led many people to question the value and veracity of science and other forms of expert knowledge. As crises like the current pandemic make clear, trust is the foundation stone of our community. Without it, even the most significant medical breakthroughs can seem like cause for suspicion.

Daniel Freeman is Professor of Clinical Psychology in the Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford.

Read: ‘COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: The Oxford Coronavirus Explanations, Attitudes, and Narratives Survey (OCEAN) II’ in Psychological Medicine.

Anything can – and very often does - happen in Oxford’s ‘Big Tent’, where academics emerge from research and teaching to engage with the public, work with creative artists and discuss major issues of today.

The Big Tent was supposed to be a...er big tent with live events and activities happening throughout the year. Organisers were actually poised to sign for a massive marquee, on the site of what will be the new Humanities Centre, when the pandemic struck. And, as with everything else, the Big Tent had to transfer online. This had obvious problems for a series of live events, but the pandemic led to the instant availability of people who might not have been available, had it actually had been under canvas.

Backed by the Humanities Cultural Programme, since last April, the Big Tent has seen almost 30 events, involving conversations with internationally well-known performers (such as Ben Whishaw) and special musical performances (for instance, of a recently discovered piece by Delius) – and some very big issues and ideas being debated (it is a university, after all). And, because it was online, it is still available, no tickets required.

We make it possible for research to benefit a wider audience....both knowledge and understanding can be exchanged in all sorts of unexpected ways

Professor Wes Williams

The academic impresario, who was ready to put the final touches to the in-real-life Big Tent, is Dr Victoria McGuinness, head of cultural programming and partnerships at TORCH (the Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities). She says, ‘We sent out a call for ideas, expecting a few, and 30 quality projects came forward...but when we saw what was happening in Italy [in terms of COVID], we knew we would not have the literal big tent.’

It was a huge shame after everyone’s work, but, says Dr McGuinness, ‘We tried to find the opportunity. Everyone is at home. We were able to get world-leading performers and creative people and we also maintained the live element with our ‘Live From’ events.’

But why is Oxford, the world’s leading research-based university, putting on shows?

According to Professor Wes Williams, TORCH Director, it is an obvious move.

‘It is an essential part of being Oxford,’ he says.

‘At TORCH we make it possible for research to benefit a wider audience. Some things obviously lend themselves better to public engagement than others,’ he maintains. ‘But both knowledge and understanding can be exchanged in all sorts of unexpected ways.’

The latest Big Tent event is the launch this week of the ambitious TIDE Salon – a collaboration between the university’s researchers on Travel, Transculturality, and Identity in England, 1550 – 1700 (TIDE project), the novelist Preti Taneja and six internationally-acclaimed musicians and spoken word artists.

It is ambitious, it is imaginative and it has brought deeply-academic research into a new open space, giving access to creative artists and members of the public. Intended to evoke the creative atmosphere of an early European or Mughal salon, the project was inspired by Professor Nandini Das, whose research focuses on travellers’ accounts from the 16th and 17th centuries.

‘It was utterly terrifying,’ says Professor Das. ‘It is not often you get to talk about early 16th century political theory with contemporary artists and musicians... and find that your throwaway reference to the Tudor ‘Register of Aliens’, which recorded immigrant presence in the country during the times of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, was picked up by the artists and has inspired some surprising and amazing work.’

Even in these difficult times, the Big Tent has been an amazing example of what people can do when they all come together. Originally, it was going to be a one-off thing, but it is fundamental that we will continue to welcome everyone into our Big Tent

Dr Victoria McGuinness

As part of her research, Professor Das and the ERC-TIDE team has put together a list of 40 key words, found in the sources of the time, which show how contested issues of identity and belonging were in this early period of British imperial ambition. The artists, working in pairs, were invited to choose three and create works for the Salon. But the academics worked closely with the artists in the early stages. The six, working in pairs, chose the words: Alien, Traveller and Savage.

‘It was entirely up to them how they used those words’, says Professor Das, ‘they had carte blanche.’

As Professor Das explains, the artists working on the word ‘alien,’ for instance, reflected on TIDE’s research into the term (which meant foreigner in the 16th century), with their own memories, of growing up as a person of colour in late-twentieth century Britain and taking refuge in the diverse world of sci-fi literature.’

The result of these conversations was the creation of three musical pieces, in collaboration with curator and creative producer Sweety Kapoor, and critically-acclaimed filmmaker Ben Crowe (ERA Films). Preti Taneja produced an entirely new piece of writing to frame the work, presenting each collaboration as fragments of archival records puzzled over by a traveller/researcher of the future, trying to make sense of history.

‘This is one of the most radically experimental things we have done throughout the project,’ says Professor Das. ‘The installation reflects the process of collaboration but also the views of the artists...they chose their own adventures and the Salon visitor is invited to take their own journey, creating their own narrative ‘.

Dr McGuinness reflected, ‘Even in these difficult times, the Big Tent has been an amazing example of what people can do when they all come together. Originally, it was going to be a one-off thing, but it is fundamental that we will continue to welcome everyone into our Big Tent.’

- ‹ previous

- 27 of 248

- next ›

The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance

The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance  The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham

The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham  Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year

Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion?