Features

An interdisciplinary seminar series considering the practices and politics of war commemoration over time has made its mark in Oxford this academic year.

The three-workshop series was organised by Dr Alice Kelly, a postdoctoral research fellow at Oxford’s Rothermere American Institute and Corpus Christi College, after she won a British Academy Rising Stars Engagement Award towards the project. Based on a course Dr Kelly initially devised for first-year undergraduates at Yale University, ‘Cultures and Commemorations of War’ has helped instigate an interdisciplinary dialogue about the history and nature of war commemoration across time, as well as its cultural, social, psychological and political aspects.

Dr Kelly said: ‘War scholars tend to work on just one war – for example, the First World War, the American Civil War or the Vietnam War. The aim of this series was to bring those academics – all working in different disciplines and at different stages, from early career researchers to advanced scholars – into conversation with one another, and into conversation with others outside the University working on war memory, including practitioners, policymakers, charities and representatives from the media and culture and heritage industries.’

The series, which featured four keynote lecturers, 27 speakers, and academic and public participants including veterans, was designed to have an intimate, thinktank-like atmosphere, where postgraduate students and early career researchers were able to play a major role. Dr Kelly said: ‘Being able to involve, train and champion postgraduate and early-career researchers has been one of the fundamental aims, and successes, of this series.’

Cultures and Commemorations of War workshop

Cultures and Commemorations of War workshopThe first workshop – ‘Why Remember? War and Memory Today’ – was held in November 2017 at the Rothermere American Institute and considered our current moment in war commemoration, drawing on the First World War centenary commemorations and the ongoing removal of confederate statues across the US. Keynote speaker was David Rieff, author of In Praise of Forgetting: Historical Memory and its Ironies. Of the response from the audience, Dr Kelly said: ‘The conversation ranged from the complex politics of national remembrance to the commercialisation of 9/11 to the recovery of bodies of First World War soldiers at Fromelles. It was both academic and personal, scholarly and reflective.’

The second event, held in December 2017 at the Imperial War Museum and titled ‘Lest We Forget? Reconsidering First World War Memory’, focused on the case study of the Great War as a means of considering ‘live’ war commemoration. The event featured a keynote talk by the Turner Prize-winning artist Jeremy Deller, who devised the Somme centenary project We’re Here Because We’re Here, which took volunteers dressed as soldiers into railway stations, tube trains and other public spaces across the UK.

Dr Kelly, who has been on a Remarque Fellowship at New York University since January, came back early from the US to run the third event, held at The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH) in late May this year. This event – ‘Seeing War: War and Cultural Memory’ – featured a keynote talk by Professor Marita Sturken, author of Tourists of History: Memory, Kitsch, and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero, which analysed the 9/11 and Flight 93 memorials. Closing with a contribution from a film historian, the day considered how different modes of seeing war shape cultural memory.

Dr Kelly added: ‘The way we remember war tells us about what our society values. The past few years have seen an explosion of commemorative activity at the local, national and international level, as well as calls to question our collective memory. Arguably there’s never been a more public culture of war memory, and memory wars, than this present historical moment. And this moment – for all of us interested in war memory – begs commentary, analysis and theorisation.’

All of the panels and keynote lectures have been podcasted and will be available soon on the website www.cultcommwar.com. The series is also on Twitter @cultcommwar. Dr Kelly is currently seeking funding to continue the series in the next academic year.

Next week, a conference hosted at Oxford will explore the latest research into ‘intact’ forests – large forested areas that remain mostly unharmed by human activity. Co-organiser Dr Alexandra Morel, a postdoctoral researcher in Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute, explains why these threatened landscapes are so important to the future of the planet.

‘Forests are among the most ecologically important landscapes on Earth. Some 1.6 billion people depend on them, and 80% of animals and plants on land live in them. Preserving forests is one of the most cost-effective solutions to mitigating climate change and could help meet 30-50% of the Paris goal of keeping Earth’s temperature rise below 2°C by 2050.

‘In particular, “intact” forests – the large, unbroken swaths of forests whose ecological functions remain unharmed by human activity – provide extraordinary benefits for protecting wildlife, human health, water supplies and indigenous communities. Furthermore, intact forests play a significant role in the fight against climate change, the most pressing environmental threat facing our planet today.

‘Despite these extraordinary benefits, intact forests are disappearing. Since 2000, intact forests have diminished by over 9% – twice the rate of overall forest clearance. If destruction continues at this pace, half of today’s intact forests will be gone by 2100.

‘For the purposes of this conference, we are defining intact forests as forests that are free of significant human-generated degradation, including loss of wildlife. That doesn’t mean a forest must be free of all human presence to be considered intact, but ecosystem science is increasingly showing that forest function is impacted by “edge effects” – the changes that take place at the boundaries between landscapes – and over-hunting. Therefore, significant areas of contiguous forest with minimal human disturbance and a large core area behave differently from smaller areas of forest within a highly fragmented landscape.

‘As for why these landscapes are important, we are keen for this conference to highlight the latest science on this question – specifically with respect to intact forest areas in tropical, temperate and boreal, or northern, regions. Some of the key values that are derived from a forest’s intactness relate to its ability to store and sequester carbon, its resilience to fire, local to regional climate regulation, watershed protection, and the ability to protect local communities from animal-borne diseases.

‘Threats to forest landscapes are manifold, primarily because their protection has not been made an international priority due to the focus on the current hotspots of deforestation and forest degradation. The fact that intact forest areas remain that way is due to their not previously being under direct threat. However, like other forest areas, intact forests are suffering hunting pressure, selective logging, mining and clearance for commodity production, which has significantly reduced their total area since 2000.

‘A multi-pronged approach will be necessary to mitigate these threats. Our conference sessions have been organised around some large topics, such as attempting to maintain intactness in logged forests, the relevance of international policies and financial instruments in incentivising intactness, and the effectiveness of protected areas, including indigenous reserves, for maintaining intact forest area. The fundamental responsibility to protect these areas lies with national and sub-national governments – however, it is increasingly recognised that these actors need additional support, both technical and financial, to achieve adequate protection of intact forests.’

The ‘Intact Forests in the 21st Century’ conference will be held in Oxford from 18-20 June.

It's a question many people thought would be impossible to answer: what did ancient Greek music sound like? Too much time had passed, and the evidence necessary to recreate and experience the sounds that the ancient Greeks heard was thought not to exist.

Professor Armand D'Angour of Oxford's Faculty of Classics thought otherwise.

It has long been taught that Hebrew liturgical music underpinned the ninth-century Gregorian plainchant that lies at the root of the history of Western music. However, Professor D'Angour's groundbreaking research has now shown that elements of the West's musical idioms may be traced much further back in time, indicating that our music has a clear basis in much earlier European practices.

Although ancient Greek music has been investigated intensively since the 16th century, for 500 years it seemed impossible to get a sense of what it would have sounded like. Now, sounds not heard for 2,000 years can be experienced thanks to collaborative research in reconstructing the melodies, instruments and rhythms. Over the past five years, accurate replicas of ancient Greek instruments have been created and have been used in performing scored texts of ancient works surviving on papyrus and stone. Auloi (double pipes played using circular breathing techniques) have been reconstructed, including one from an original second-century instrument now on display in the Louvre. The kithara (a stringed instrument that was used as a large concert lyre) has been remodelled with reference to images found on ancient vases. The integration of these instruments into this research gives an authentic feel to the sounds that we hear.

The texts of ancient Greek poetry were intended to be sung or spoken along with music. The earliest music that may be speculatively recreated is that of Homer, who composed his epics around 700 BC to the accompaniment of a four-stringed lyre. The sound of epic song has been recreated (following work by the late Professor Martin West) using the four notes that would have been available to Homer, and improvised on the basis of the pitch inflections of ancient Greek (in which the syllables of words went up and down in pitch at specified places).

In other cases, fragments of the melody and rhythms have survived to give a more complete sense of the original piece. The most valuable of these is a papyrus fragment with the music from a tragedy, Euripides' Orestes, originally produced in 408 BC. Another source, a stone tablet from Delphi, shows the melodic notation of Athenaeus' Paean from 127 BC. Professor D'Angour has worked to fill in the gaps, and the performance of these pieces provides a thrilling insight into what the ancient Greeks would have heard.

So what's next? Currently, Professor D'Angour is working with around 30 further documents of ancient music to continue to recreate the works that were played and sung. The aspiration is to put on, for the first time since antiquity, an ancient tragedy accompanied by the kind of music that it would originally have been accompanied by, perhaps in one of the great theatres that survive from the ancient world.

Adapted from an article by Exzellenzcluster Topoi.

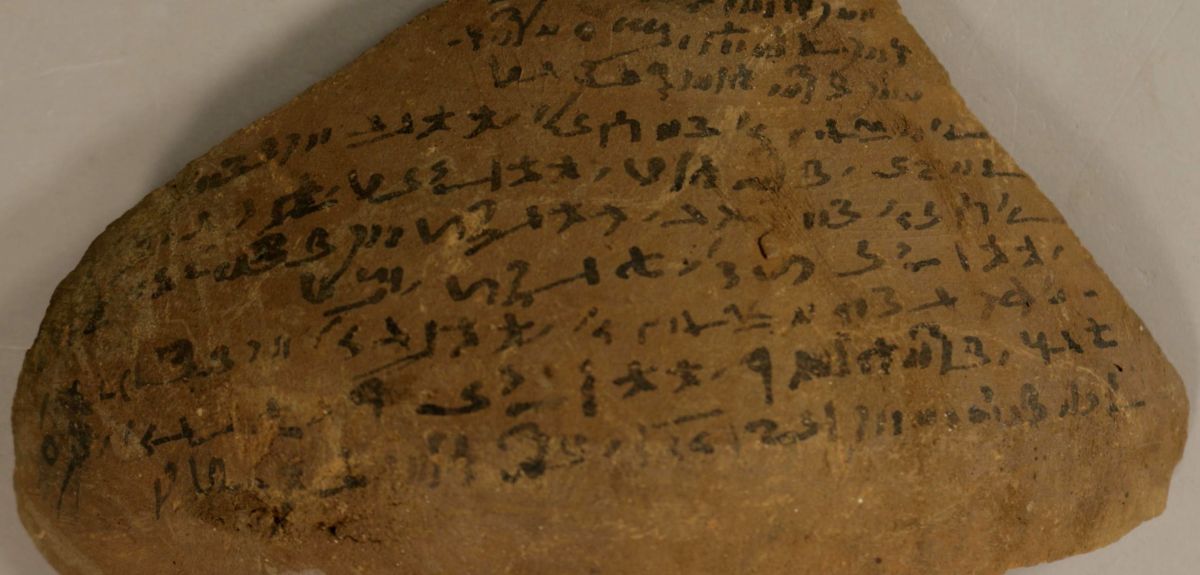

Egyptian astronomers computed the position of the planet Mercury using methods originating from Babylonia, finds a study of two Egyptian instructional texts from Oxford's Ashmolean Museum. The study was carried out by Mathieu Ossendrijver, a historian of ancient science at Humboldt University Berlin and Exzellenzcluster Topoi, and Andreas Winkler, an Egyptologist at Oxford University's Faculty of Oriental Studies. The instructional texts date to 1-50 AD and are written in the Demotic language, a late stage of ancient Egyptian, on two 'ostraca' (potsherds, or broken pieces of ceramic material). They are the only known texts from Greco-Roman Egypt with instructions for computing astronomical phenomena with Babylonian methods.

The instructions correspond exactly to methods invented in the ancient state of Babylonia several centuries earlier (400-300 BC). Surprisingly, the ostraca employ a mathematical formulation not found in Babylonian texts but whose existence has long been suspected by historians of astronomy. The ostraca prove that native Egyptian scholars were as competent in Babylonian astronomical computation as their colleagues writing in Greek, suggesting a more important role for native Egyptian scholars in the transmission of Babylonian astronomy to Greco-Roman Egypt than previously thought.

By the early second century BC, Babylonian astrology and astronomy had spread to Egypt. Like their Babylonian colleagues, Egyptian astrologers began to produce horoscopes in order to determine the fate of a newborn. The production of a horoscope required computing the zodiacal positions of the Moon, the Sun and the five planets known in antiquity: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Both Demotic horoscopes and Greek horoscopes have been found in Egypt, and in 1999 the American historian of astronomy Alexander Jones proved that some Egyptian astrologers writing in Greek were using Babylonian methods. But until now little has been known about the computational methods of the native Egyptian astrologers writing in Demotic.

The two newly identified Demotic texts with computational instructions shed new light on the mathematical skills of the native Egyptian astrologers. Both ostraca contain instructions regarding three distinct Babylonian algorithms. Each of them is concerned with a particular phenomenon of Mercury: its first appearance as an evening star, its first appearance as a morning star, or its last appearance as a morning star. The inscriptions offer the first unequivocal proof that native Egyptian astrologers, like their colleagues writing in Greek, were capable of computing positions of Mercury, a planet with a comparably complicated motion, using Babylonian methods. An analysis of the instructions suggests that the native Egyptian scholars adapted these methods before their colleagues writing in Greek, as well as independently of those colleagues. First, the ostraca predate all known Greek tables for Mercury that were computed with these methods, and are in fact the only instructional texts with Babylonian astronomy that have been found in Egypt thus far. Second, they use a Babylonian loanword for 'degree', while the astrologers writing in Greek used a Greek word for this.

A surprising aspect of the instructions is that they employ a mathematical formulation that is unknown from Babylonia. While the Babylonians directly computed the variable distance travelled by Mercury along the zodiac – for example, between two occurrences of its first appearance as an evening star – the Egyptian scholars first divided the zodiac into tiny steps of variable length. The distance travelled by Mercury was then obtained by counting off a fixed number of these steps, with identical results to those obtained by their Babylonian counterparts. In 1957, the mathematician Bartel van der Waerden first suggested the existence of this alternative formulation. While it has not yet been identified in any Babylonian text, we now see it in these two Demotic texts written by native Egyptian scholars.

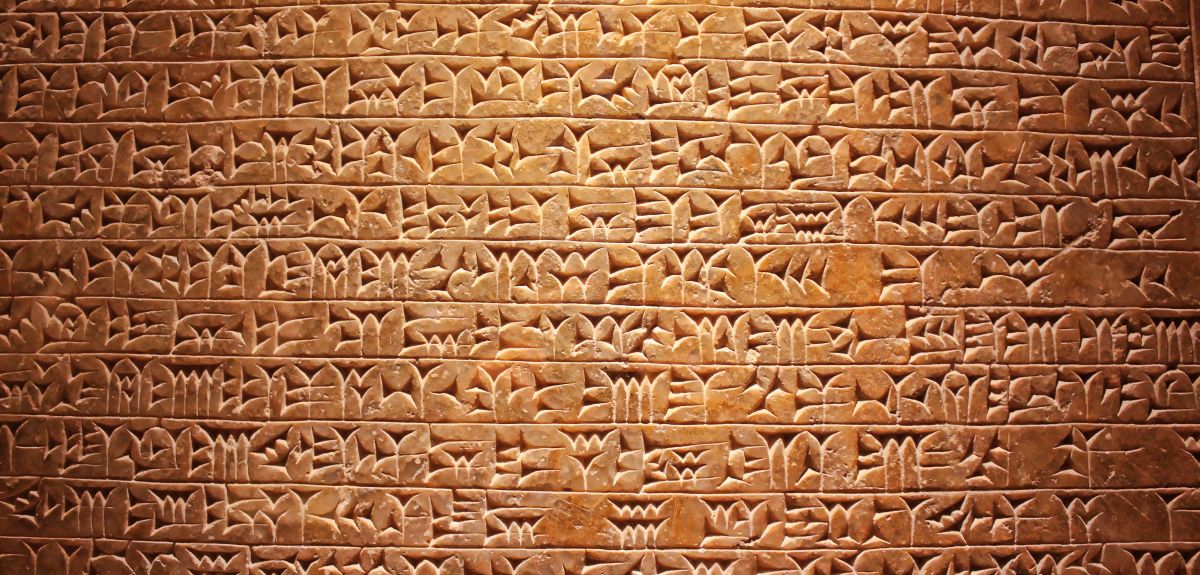

Chronicling 'half of human history', cuneiform texts provide a rich source of information on the rise and fall of ancient civilisations and the daily lives of people of the past.

And with more than half a million original and unique artefacts in museums worldwide, cuneiform texts from ancient Iraq, Iran and Syria – dating from around 3500 BC to the year 0 – represent a resource richer than any other recovered from the ancient world.

The cuneiform system itself is characterised by wedge-shaped signs on clay tablets, representing words or syllables in long-forgotten languages such as Akkadian and Sumerian.

Working with colleagues around the world, Oxford's Professor Jacob Dahl has been co-leading a project to digitise and disseminate many of these important cuneiform texts. Most recently he has spearheaded a collaboration to include the cuneiform text artefacts in the National Museum of Iran (NMI) in the growing online corpus of cuneiform texts.

Professor Dahl, a member of Oxford's Faculty of Oriental Studies and a fellow of Wolfson College, said: 'Cuneiform texts cover half of human history, and the sources from ancient Iraq, Iran and Syria are richer than those of any other ancient civilisation. They cover all topics and genres and include thousands of private letters, lexical texts, literary compositions and above all administrative texts.

'The NMI collection is particularly important for the early period, when cuneiform writing was invented in Iraq and spread into Iran, where a related writing system called Proto-Elamite was developed. The sources for this still-undeciphered writing system are split between the Louvre in Paris and the NMI.

'The Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative, which I co-lead, has digitised much of the Louvre collection of cuneiform already, and bringing in the NMI therefore draws together two parts of the same ancient collection. The NMI also holds significant collections of clay tablets, bricks and stones featuring texts from other periods and in other languages – in particular Elamite and Old Persian – which are of interest to specialists well beyond the narrow field of Assyriology.'

Jacob Dahl scans Proto-Elamite tablets in the National Museum of Iran, Tehran.

Jacob Dahl scans Proto-Elamite tablets in the National Museum of Iran, Tehran.The digitisation project was proposed two years ago by Professor Dahl and Jebrael Nokande, Director of the NMI. The first group of Proto-Elamite tablets was scanned and digitised in January and May this year.

Professor Dahl said: 'Since beginning my work on Proto-Elamite tablets almost two decades ago I have waited for an opportunity to work on the texts in the NMI. I spent a lot of effort digitising cuneiform collections in Syria prior to the current unrest, which highlighted for me the need to secure all collections both here and abroad through digitisation and web dissemination.

'The field in general is in the middle of a digital transformation, and it is hard to overestimate the impact of making this collection openly accessible through the internet. Scholars will be able for the first time virtually to reassemble the ancient textual record recovered during the excavations of Susa (modern-day Shush in Iran). It will also open, I hope, avenues for collaboration and sharing of scholarly knowledge between researchers from Iran and the UK concerning a variety of topics, expanding beyond my own subject of Assyriology.'

- ‹ previous

- 67 of 248

- next ›

The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance

The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance  The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham

The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham  Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year

Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion?