Features

Niklas Bobrovitz, a PhD candidate in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford and an honorary fellow at the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, writes about his latest research into the medications that can reduce emergency hospital admissions.

Emergency hospital admissions are rising and, increasingly, policy-makers, clinicians and patients are worried about their effect on cancellations of elective procedures, prolonged waiting times, in-hospital infection rates and costs. However, identifying useful strategies for reducing admissions has proved problematic – interventions designed to reduce hospitalisations often achieve no real-world benefit, yet consume scarce health resources.

One promising intervention that has received little attention is medications; those which help a patient to avoid hospitalisation represent high-value activity in a patient’s overall care. Medications can reduce admission rates by preventing illnesses or mitigating symptoms and exacerbations that would have otherwise required urgent health care.

Our new study in BMC Medicine, therefore, aimed to identify and prioritise medications that have been shown in systematic reviews to prevent patients from requiring emergency hospital care.

What did we do?

We searched for systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials in adults that reported hospital admissions as an outcome. We then assessed the quality of evidence using GRADE criteria. We cross-referenced effective medications with high or moderate-quality evidence with UK, USA and European clinical guidelines to determine which had an acceptable overall balance of benefit to harm.

What did we find?

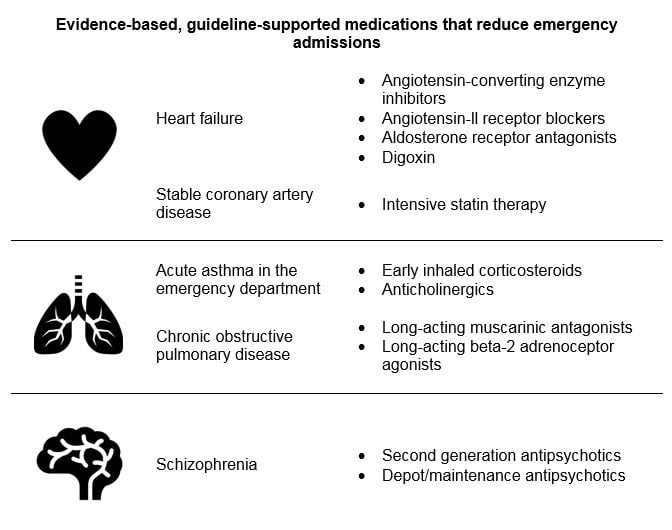

We found 140 systematic reviews, including 1,968 randomised controlled trials and 925,364 patients. We identified 11 medications that significantly reduced emergency hospital admissions, were supported by high or moderate-quality evidence, and were endorsed in clinical guidelines.

Evidence-based, guideline-supported medications that reduce emergency admissions

Evidence-based, guideline-supported medications that reduce emergency admissionsWhat does this mean?

Using the 11 medications that we identified is clinically appropriate and will significantly reduce emergency hospital admissions for patients with heart failure, coronary artery disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and schizophrenia.

In some health systems, these medications are already prescribed as part of routine clinical practice. However, there is evidence of significant variation in their use in the UK, USA and Europe, including under-prescribing and under-dosing. Therefore, policy-makers and clinicians should consider monitoring and improving use of these medications as a strategy to alleviate pressures on secondary acute care.

Existing mechanisms for quality measurement and improvement could be utilised. For example, the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework is a pay-for-performance incentive programme that has reduced prescribing gaps and improved prescribing efficiency. The medications we identified should be considered for inclusion in these types of quality assurance and incentive systems.

Our results may also be used to inform shared decision-making. When communicating treatment options with eligible patients, clinicians could discuss the ability of these medications to reduce the risk of being hospitalised. Given that most patients prefer to stay out of hospitals, we hope that our findings will help to inform their decisions.

This blog first appeared in BMC Medicine.

The study, titled 'Medications that reduce emergency hospital admissions: an overview of systematic reviews and prioritisation of treatments', can be accessed here.

How does £130 in driving fines result in a young man taking his own life?

That question lingers long after the credits roll on the BBC drama ‘Killed by my debt’, which tells the harrowing true story of Jerome Rogers, a 19-year-old courier, who tragically took his own life after debts stemming from two outstanding motoring offences spiralled beyond his control – from £65 each, to more than a thousand pounds within a matter of months.

A combination of unfortunate and all too common circumstances – flexible, insecure employment, working class background, age and unique health factors, prevented him from clearing the debts and ultimately led to his untimely death.

These factors not only made him ripe for exploitation in today’s society, but were also enabled by the very economic structure that now underpins it, the gig-economy. If at this point, you’re thinking, ‘the what?’ you are not alone. ‘Gig-economy’ is a phrase commonly used in society, but little understood by many.

To bring some clarity to the subject, ScienceBlog talks to Dr Alex Wood, a sociologist and researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute, who focuses on the changing nature of employment relations and labour markets, to breakdown everything you need to know about the ‘gig-economy’ and how it could affect you in the future.

What is the gig-economy and how does it work?

The gig-economy is the way in which people are now finding work in non-standard ways. So, instead of working for a traditional employer, they access paid-work through online platforms which enable workers to be hired to do a specific task, or gig. For example, driving jobs like Uber and delivery tasks such as Deliveroo. But also traditional freelance tasks, like website and graphic design.

It’s important to understand that the system of work comes with no frills. Zero-hour contracts and no benefits like holiday pay, sick pay or even a minimum wage.

How has it affected employment?

People are basically working in a much more flexible way. They can be juggling multiple-tasks any given time, and all hours of the day. There is no fixed way of working – the days of the 9-5 are long over for many workers.

On the one hand, this can be a positive set-up if you have control of the work you do, and are able to choose for yourself who you work for, what tasks you perform and when you do them. But to be in this privileged position your skills have to be in high demand, and the reality is that a lot of people are competing for these roles.

When you don’t have this control it can lead to employment instability and insecurity.

People have to work to survive, and if you don’t know where your next hour of work is coming from it can make it impossible to budget and plan for everyday life such as childcare, social life and holidays. Which can lead to people becoming really isolated.

It’s important to understand that the system of 'gig' work comes with no frills. Zero-hour contracts and no benefits like holiday pay, sick pay or even a minimum wage.

How can this instability affect people’s lives?

In these circumstances workers become desperate and feel they have to work whenever an employer wants them to. They relinquish all control which can be incredible stressful, mentally and physically. Control is key.

Often in the press the gig-economy is discussed positively as something mutually beneficial to employers and workers. But in reality it is a trade-off. The reasons why each side wants flexibility are very different.

If the employee is in control, the employer is not, and they are in a position where they have to match labour supply to customer demand. But, for the worker, it is about survival and trying to make a living – as we have seen horrifically reflected in the case of Jerome Rogers.

Who is most at risk?

People competing for less in-demand skilled roles can unfortunately be taken advantage of. Unlike more skilled roles, where there is a much smaller pool of people who can perform them, there are a lot more people that want and can do the job. That means these workers do not have alternative opportunities, so if a client or platform makes unreasonable demands or wants them to work anti-social hours, they have no other choice but to do it. People need to work to survive, so they have to work whenever they are asked to.

We need to rethink our understanding of workers’ rights and employment law. The purpose of the law is to protect people in a vulnerable position, if it is not doing that anymore we need to change the law to make sure that these people are protected.

Most workers who are part of the gig-economy are also not part of a trade union, so they don’t have the protections that come from having a collective voice, which makes them much more vulnerable.

Who has the most to gain?

If workers have skills that are in demand then it can be positive for them, because they can pick and choose who they work for and when. But, in most areas there is a lack of high quality jobs and there are no good quality alternatives available.

For employers however, the benefits are much more obvious. Employing people by task allows a business to reduce labour costs and avoid paying for services that were once expected such as pensions.

Can people make the gig-economy work for them against the odds?

Collective organisation is really important, for example being a part of a trade union.

It is interesting that just last week, Deliveroo workers in London and across Europe went on strike to protest changes to their pay. Even though protections did not exist for these workers when the gig-economy structure launched, they are working collectively to put them in place. Workers who are in a vulnerable position should be able to come together and protect themselves.

Can you tell us a little about your research?

At the moment I am looking at collective organisation and community amongst gig economy workers who are doing remote gig work, in my paper 'workers of the internet unite?'

They operate on similar gig-economy style platforms to Uber and Deliveroo, which perform direct tasks, only these people work remotely from anywhere in the world, supporting digital labour, such as transcription and editing. Even these workers are coming together to create collective organisation.

What can be done to regulate the system and make it fairer?

We need to rethink our understanding of workers’ rights and employment law. The purpose of the law is to protect people in a vulnerable position, if it is not doing that anymore we need to change the law to make sure that these people are protected.

Trade unions should also be able to represent them. Often these platforms claim that workers cannot have a trade union because technically they are a business working for a client, not a direct employee.

There needs to be a recognition that if people are in a dependent situation they are automatically more vulnerable, and should have labour protections. For example, a minimum wage, sick pay and holiday pay. Things that were considered a right in traditional jobs should also be a right in the gig economy.

Dr Wood's paper 'Workers of the internet unite?' is available to view here

Professor Xiaolan Fu of the Oxford Department of International Development (ODID) explains how a proposed new approach to measuring global trade would suggest that the US trade deficit is actually about half as big as official figures report.

As the world moves towards a new trade war, with the imposition of US tariffs on goods from the EU, China, Canada and Mexico, having reliable international trade statistics is more important than ever.

However, it is widely recognised that the way in which global trade is officially measured and recorded has failed to keep pace with the increasingly complex ways in which trade is actually conducted.

This is because international statistics primarily record trade in goods and services and fail to account for the growing trade in ‘intangibles’ – such as patents, brands, trade secrets or ‘know-how’.

Nor do they adequately reflect the fact that trade increasingly occurs in global ‘value chains’, in which different tasks and business functions are dispersed across multiple companies in different regions or countries. Tracing how value is created and how trade flows across these chains can be complex.

So in response, we have developed a new approach to measuring global trade that seeks to bring together measurement of trade in goods and services with trade in intangibles and to reflect the fragmented and segmented nature of global production.

In the model, we identify five modes through which trade in intangibles takes place within global value chains: licensing; foreign direct investment (FDI); outsourcing; collaboration/alliances; and the provision of consultancy services.

We then detail how the value of intangibles is captured in each of these modes – for example through royalty fees in the case of licensing, or through dividends in the case of FDI – and how these might be accurately recorded in a country’s exports and imports. While these flows are currently included in the balance of payments in different ways, for example as investment income, they are not directly attributed to the trade process.

Applying this proposed measurement approach to the available data produces an interesting result: we estimate that the overall US trade deficit would have been around $358 billion in 2016, as opposed to the official figure of $750 billion.

This is a conservative estimate, as it does not take account of intangibles income accrued to US firms through outsourcing activities because of difficulties in tracing such information.

The proposed measure offers a comprehensive picture of the full range of trade interactions between countries and would therefore offer a more accurate basis for policy discussions about global trade imbalances and the impact of globalisation.

In particular, policy could focus on ensuring that the benefits of trade in intangibles – which are currently concentrated in the hands of a few owners of the intangibles, along with a small community of skilled researchers and technicians who created them – are distributed more equitably.

Policies could also seek to encourage multinational enterprises (MNEs) to transfer the gains from trade in intangibles back to their home countries and to curb tax avoidance.

Read the paper on which this article is based here.

Xiaolan Fu is Professor of Technology and International Development and Director of the Technology and Management Centre for Development (TMCD) at ODID.

Matt Costa, Professor of Orthopaedic Trauma at the University of Oxford and President elect of the Fragility Fracture Network (FFN), explains the need for global action to provide better care for people suffering from hip fractures and other fractures that result from increased fragility.

The global population is currently undergoing the greatest demographic shift in the history of humankind. A direct consequence of this “longevity miracle” – if left unchecked – will be an explosion in the incidence of chronic diseases afflicting older people.

A new Global Call to Action for better care for people suffering from hip fractures and other fractures that result from increased fragility illustrates that for the first time, the leading organisations in the world have recognised the need for collaboration on an entirely new scale.

The UK has recognised the need for multi-disciplinary care for patients with fragility fracture and has the world’s largest national hip fracture database (NHFD). These are essential parts of our response to the coming fragility fracture crisis, but we need to do more. Here in Oxford, we will use the World Hip Trauma Evaluation (WHiTE) research project to collect research data from around the world to improve quality of life for patients everywhere.

In the absence of systematic and system-wide interventions, this tsunami of need is poised to engulf health and social care systems throughout the world. Osteoporosis, falls and the fragility fractures that follow will be at the vanguard of this battle which is set to rage between quantity and quality of life.

By 2010, the global incidence of one of the most common and debilitating fragility fractures, hip fracture, was estimated to be 2.7 million cases per year. Conservative projections suggest that this will increase to 4.5 million cases per year by 2050. While all countries will be impacted, in absolute terms, Asia will bear the brunt of this growing burden of disease, with around half of hip fractures occurring in this region by the middle of the century. And the associated costs are staggering: in Europe in 2010, osteoporosis cost Euro 37 billion, while in the United States estimates for fracture costs for 2020 are US$22 billion.

If our health and social care systems are to withstand this assault, a robust strategy must be devised, and an army of health professionals amassed to deliver it. This strategy must transform how we currently treat and rehabilitate people who have sustained fragility fractures, in combination with preventing as many fractures from occurring as possible. The latter can be achieved in part by ensuring that health systems always respond to the first fracture to prevent second and subsequent fractures. In short, let the first fracture be the last.

A major step towards making this aspiration a reality has occurred today with publication of a Global Call to Action to improve the care of people with fragility fractures. Endorsed by 80 leading organisations from around the world, covering the fields of medicine and nursing for older people, orthopaedic surgery, osteoporosis and metabolic bone disease, physiotherapy, rehabilitation medicine and rheumatology, the case for transformation of the following aspects of care has been made:

• The surgical and medical care provided to a person hospitalised with a hip fracture, a painful fracture of the spine and other major fragility fractures.

• Prevention of second and subsequent fractures for people who have sustained their first fragility fracture.

• Rehabilitation of people whose ability to function is impaired by hip fractures and other major fragility fractures, to restore their mobility and independence.

The Call to Action was conceived at an annual congress of the FFN, when six leading organisations came together to determine how they could most effectively collaborate to improve fracture care globally. The lead author of the publication, Professor Karsten E. Dreinhöfer said 'Fragility fractures can devastate the quality of life of people who suffer them and are pushing our already overstretched health systems to breaking point.' He added 'as the first of the baby boomers are now into their seventies, we must take control of this problem immediately before it is too late.'

The Global Call to Action proposes specific priorities for people with fragility fractures and their advocacy organisations, individual health workers, healthcare professional organisations, governmental organisations and nations as such, insurers, health systems and healthcare practices, and the life sciences industry. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has declared the years 2020-2030 to be the “Decade of Healthy Aging” and later this year the United Nations (UN) will hold its Third High-level Meeting on Non-Communicable Diseases. The authors highlight the opportunity for WHO and UN to consider the recommendations made in the Global Call to Action as an enabler for their global initiatives.

The pace of technological development has outrun policy discussions at both a national and international level in recent years. Drone use in particular has improved the efficiency of data collection, allowing teams to monitor and survey large areas without impacting the landscape, day to day life, or their own safety. However, there are some concerns, particularly around ethics, long-term safety and security.

In view of such change, Oxford University’s Centre for Technology and Global Affairs joined forces with drone companies such as Measure, to explore potential governance models for how civil airspace and how the skies in general could be best regulated moving forward.

The Centre, a pioneering interdisciplinary research outlet focused on understanding how technology influences business and governance today, held its first ‘Robotics Skies Workshop: The Role of Private Industry and Public Policy in Shaping the Drones Industry’ (June 21st and 22nd).

The event brought together practitioners, policymakers, and experts from industry, government, and academia to assess the governance and regulatory challenges associated with the burgeoning global Unmanned and Autonomous Aerial Vehicles (UAVs & AAVs) industry.

Lucas Kello, Director of The Centre for Technology and Global Affairs, said: ‘Recent technological advances have outpaced policy discussions. In view of such a development, the Centre's researchers are undertaking interdisciplinary research at the intersection of technology, industry, and government policy.’

The programme included discussions around the latest developments in the sector, such as; the use of drones-as-a-service, Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM), technological advances in geo-fencing, industry-led initiatives in raising safety awareness of drones users, as well as the interplay between data, digitalization, and automation in facilitating future commercialization of UAV and AAV technologies.

High-level speakers at the workshop included Matthew Baldwin, Deputy Director-General of Mobility and Transport from the European Commission, Pavel Abdur-Rahman, Data Scientist and Partner at IBM, Jessie Mooberry, Head of Deployment with Altiscope from Airbus, Christian Struwe, Head of Public Policy Europe at DJI, among others.

The Centre's Founding Donor, Artur Kluz, reflected: "I am pleased to see that the first workshop on the future of autonomous drones perfectly fulfils the Oxford Centre's long-term vision to serve as a powerful policy-building hub for the beneficial development of breakthrough technologies."

Attendee Ludovic Drouin, Science and Technology Officer from the French Embassy in London commented on the value of the workshops, describing it as ‘a tremendous opportunity to witness the state of the art in UAVs, the workshop is foremost in shaping a potential regulatory framework and in understanding inherent challenges associated with the future of the industry.’

Jessie Mooberry from Airbus added: ‘By convening industry, government, academia, and civil service, Robotic Skies fostered necessary deep and wide conversations about the role of automation in our airspace as well as the physical and digital infrastructure required to enable this future.’

Workshop attendees smile for the camera drone.

Image credit: Diego Avesani

Workshop attendees smile for the camera drone.

Image credit: Diego AvesaniAs a global research and policy-building initiative focused on the impact of technology on international relations, government, and society, The Centre serves as a bridge between researchers and the worlds of technology and policymaking, intended to facilitate policy resolution around pressing problems across six technological dimensions: Artificial Intelligence, Robotics, Cyber Issues, Blockchain, Outer Space, and Nuclear Issues. Artur Kluz is Founding Donor of the Centre for Technology and Global Affairs and the Centre was supported by core funding from Kluz Ventures.

Brandon Torres Declet from Measure – who collaborated with the Centre on the workshop, said: ‘It was an honor to participate with Oxford University and drone experts from industry and government to begin an important discussion at the intersection of UAV technology and government policy.’

Robotic Skies is the first in a series of planned events at the Centre, aimed at creating a sustainable forum for inter-sectoral dialogue and driving wide-spread knowledge exchange across industries and disciplines.

- ‹ previous

- 65 of 248

- next ›

Teaching the World’s Future Leaders

Teaching the World’s Future Leaders  A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future

A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance

Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance

The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance  The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham

The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham  Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year

Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage