Features

Professor Mark Graham

Professor Mark GrahamWithout data annotators creating datasets that can teach AI the difference between a traffic light and a street sign, autonomous vehicles would not be allowed on our roads. And without workers training machine learning algorithms, we would not have AI tools such as ChatGPT.

Professor Mark Graham researches global technology through the eyes of the hidden human workforce who produce it. He argues that AI is an "extraction machine", churning through ever-larger datasets and feeding off humanity’s labour and collective intelligence to power its algorithms.

We caught up with Mark to discuss some of these issues.

In talking about the AI technologies we rely on, you mention the "countless humans forced to work like robots, toiling in monotonous low-paid jobs just to make such remarkable machines possible" -- who are these people, and what sorts of jobs are they doing?

There is a whole range of ‘data work’ needed to make our digital lives possible. Data annotators label data with tags so that it can be understood by computer programs. Content moderators sift through digital content in order to remove harmful content that breaches company guidelines. If you have ever interacted with any form of AI, whether it be a chatbot, a search engine, a social media feed, a streaming recommendation system, or a facial recognition system, data workers have had a hand in building or maintaining those systems.

The root cause of the problems encountered by data workers lies in the power imbalance between them and the institutions that govern their jobs… It is unlikely that any of the issues data workers experience will ever be meaningfully addressed without workers building their collective power in movements and institutions.

You talk about "building worker power", as a step towards redressing some of the issues of the hidden labour of AI — I guess this is quite difficult when these jobs are so atomised, and the workforce so expendable?

The root cause of the problems encountered by data workers lies in the power imbalance between them and the institutions that govern their jobs. Historically, when social movements achieve lasting change, it's often through organizing a critical mass of people to push for policies that address systemic inequalities. It is therefore unlikely that any of the issues data workers experience will ever be meaningfully addressed without workers building their collective power in movements and institutions.

However, data workers face serious barriers to ever building that power. The jobs that they undertake are relatively footloose and standardised, and, as a result, are carried out in a planetary-scale labour market. Their jobs can be quickly shifted to the other side of the planet.

There are no easy ways for workers to build collective power under these sorts of conditions. Data workers in a country like Kenya or the Philippines have an enormous structural disadvantage. However, that is not to say that organizing is impossible. In production networks that are organised globally, workers will increasingly also need to explore ways of organising across geographies. This will undoubtedly take a range of forms, but will all need to be rooted in the principle that workers acting collectively will be able to demand better conditions for everyone in a production network. Isolated efforts, by contrast, are unlikely to achieve lasting change.

A requirement of accountability is visibility. What are some of the ways that this labour is hidden from us -- and why? How could it be made more open and visible, more recognised?

The labour in AI production networks is almost always hidden from view. If you drink a cup of coffee or buy a pair of shoes, you probably have a conception that at some point that coffee passed through the hands of a plantation worker or the shoes were assembled by someone in a sweatshop. However, precisely because AI presents itself as automated, very few people can imagine what the human labour on the other side of the screen looks like. AI companies are complicit in this subterfuge. They want to present themselves as technological innovators rather than as the firms behind vast digital sweatshops.

Because AI presents itself as automated, very few people can imagine what the human labour on the other side of the screen looks like. AI companies are complicit in this subterfuge.

Because of this enormous gap between how tech companies present themselves and the actual on-the-ground conditions experienced by workers in those production networks, I started the Fairwork project. Fairwork evaluates companies against principles of decent work and gives every company a score out of 10 based on how well they stack up against those principles. To date, we have scored almost 700 companies in 38 countries. Doing this work has encouraged a lot of companies to make improvements to the working conditions of their workers to receive a higher score.

The next phase of our project will involve going to the lead firms in AI production networks, the brands that consumers are familiar with, and letting them know that we are going to start holding them accountable for all the working conditions upstream in their production networks. We will constructively work with them to embed principles of fair work into their contracts and supplier agreements, but also use our research to hold them accountable when they fail to do so.

Watch Mark’s latest video highlighting the hidden cost of AI and the implications of this ever-evolving technology for the thousands of AI workers toiling away behind the scenes to deliver AI powered services.

I guess an obvious solution to some of these issues is regulation -- workers should be protected in whatever jurisdiction they are working, and wherever in the production chain they sit. What efforts are being made in this area?

The planetary labour market that much of this work is traded in makes it difficult for regulators in the Global South to raise conditions. If regulation raises costs in Kenya, those jobs can move to India. If regulation in India raises costs, those jobs can move to the Philippines. These dynamics create a ‘race to the bottom’ in wages and working conditions, leaving regulators having to choose between bad jobs or no jobs. As the economist Joan Robinson famously said, ‘The misery of being exploited by capitalists is nothing compared to the misery of not being exploited at all.'

However, even though the global geography of the labour market neuters the ability of regulators to act in the Global South, it strengthens the hand of regulators in the Global North. Regulators in countries that are home to a lot of the demand for digital products and services have the ability to play an outsized role in setting standards. The EU's proposed Supply Chain Directive is a good example of this. It aims to make companies operating in the EU accountable for human rights and environmental impacts throughout their global supply chains. Because few AI companies will want to forgo being able to sell to consumers in the EU, this directive has the potential to improve conditions for the many workers in countries with weak labour protections.

Much of the discussion about AI has been focused on existential risks that it might present in the medium- to long-term future. However, the real risks of AI are already right here in the present.

Finally, your assessment of the AI industry is pretty bleak, that "workers are treated as little more than the fuel needed to keep the machine running" — and that this is happening to all of us, right now. What are some of the key issues and battlegrounds in which this question will be played out in the coming years?

Much of the discussion about AI has been focused on existential risks that it might present in the medium- to long-term future. However, the real risks of AI are already right here in the present.

A few decades ago, anti-sweatshop campaigns shifted attention to the plight of garment workers, and shifted the onus of responsibility for those workers onto the brands who sell clothes. Those campaigns did not fully eradicate sweatshops, but have been an important moment on a path to normalising the idea that lead firms in production networks have the potential power to impose decent work conditions throughout a supply chain. If we are to head towards a fairer future of work, one of the key battlegrounds will have to be ensuring that big tech companies take responsibility for the conditions of all workers in their supply chains.

Because tech companies have, to date, taken on very little of this responsibility, pressure will be required from consumers, policy makers, and workers. Consumers will have to recognise that they are complicit in the conditions of workers who made or maintained the product or service that they are using. Policy makers will have to realise that a laissez-faire approach to regulation is only serving to increase inequalities. And workers will have to find ever more creative ways to organise across supply chains in order to hold companies accountable. Until we all force these companies to change, we will only continue to be nothing more than fuel for the machine.

***

Professor Mark Graham was talking to the OII's Scientific Writer, David Sutcliffe.

Mark Graham is Professor of Internet Geography at the Oxford Internet Institute, where he leads a range of research projects spanning topics between digital labour, the gig economy, internet geographies, and ICTs and development. He's also the Prinicipal Investigator of the participatory action research project Fairwork, which aims to set minimum fair work standards for the gig economy.

Read his latest book: James Muldoon, Mark Graham, and Callum Cant (2024) Feeding the Machine. Canongate.

Kamanamaikalani Beamer. Image credit: Matthew Mulholland, Oxford Media Group.

Kamanamaikalani Beamer. Image credit: Matthew Mulholland, Oxford Media Group.

Throughout the event, participants were encouraged to engage with art, film, and ceremonies led by indigenous elders that aimed to showcase the importance of nature and our interconnectedness with it. The conference venue, at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, further underscored the need to draw on our evolutionary past to plan better for a flourishing future.

Discussing the importance of nature connection, speakers put forward that we are not separate from the environment, but an integral part of it. This understanding can then foster a deeper commitment to protecting our natural world.

Delegates were challenged to consider the benefits of nature-based solutions beyond climate change mitigation, and to reflect on ways to reconnect with nature on a deeper level.

A mural painted in real-time during the conference. Image credit: Matthew Mulholland, Oxford Media Group.

A mural painted in real-time during the conference. Image credit: Matthew Mulholland, Oxford Media Group.

Ceremonies and Cultural Integration

Delegates experienced the unique confluence of science, art, music, short films, and ceremonies, inviting them to pause, reconnect with nature, and contemplate our shared humanity and common ancestry with all of life. Indigenous elder Mindahi Bastida guided elemental ceremonies that marked the opening and closing of the event.

Invaluable Indigenous Perspectives

‘There is no separation between nature and culture’ conference speaker Kamanamaikalani Beamer, University of Hawai'i at Mānoa.

Humans are not separate from the environment but an integral part of it. This fundamental understanding fosters a deeper commitment to protecting and preserving our natural world. Our connection with nature is not just a philosophical concept; it is a practical, essential pathway to effective nature-based solutions

By respecting indigenous sovereignty, protecting ecosystem integrity, and embedding human rights, nature-based solutions can play a key role in addressing the climate and biodiversity crises. As a global community, we need to take bold, informed, and collaborative actions to care for that which sustains us.

Professor Nathalie Seddon, Director of the Nature-based Solutions Initiative at the University of Oxford

Holistic Solutions and Community Empowerment

There is an urgent need for holistic approaches to environmental issues, with integration across disciplines to break down research and policy silos. This fosters collaboration and innovation, leading to more comprehensive and effective solutions.

Call to Action

Participants unanimously called for bold, collaborative actions to safeguard our planet's biodiversity and support social-ecological flourishing. The conference concluded with a shared commitment to scaling nature-based solutions ethically and effectively, ensuring they contribute to building an economy that is in service of the flourishing of life on Earth.

Recordings of the conference sessions will be available soon on the NbSI YouTube channel.

Astrophoria’s Programme Director, Dr Jo Begbie, speaks about the programme’s first year and shares her highlights.

As the end of the academic year fast approaches, twenty-two students from across the UK will soon be completing the University’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year. Providing a one-year fully funded course for UK state school students who have experienced severe personal disadvantage or disruption to their education, the Astrophoria programme is designed to enable motivated students to reach their academic potential by bridging the gap between A-Levels and Oxford’s challenging undergraduate degrees.

It is led by Dr Jo Begbie, who has had plenty of experience of educational environments prior to arriving in Oxford in 2004: completing her undergraduate degree at Leeds, a PhD at UCL, and postdoctoral research at King’s College, London. At Oxford, Jo started a research lab and took up the post of lecturer in Medicine, before becoming a Tutor in Medicine at one of Oxford’s colleges, Lady Margaret Hall.

Students meet Oxford's Vice-Chancellor, Professor Irene Tracey and Astrophoria Director, Jo Begbie, during their orientation week

Students meet Oxford's Vice-Chancellor, Professor Irene Tracey and Astrophoria Director, Jo Begbie, during their orientation week“And then as a medicine tutor doing admissions, I could see that there were students that had potential but weren’t going to get the grades to come into Oxford, and often they were young people from less advantaged backgrounds – Astrophoria is about putting those two things together.”

Foundation Years can mean different things for different institutions, says Jo. At Oxford, the Astrophoria programme – which follows on from a college-based initiative Jo was involved in at Lady Margaret Hall – provides lower contextualised offers for entry to study. But importantly, according to Jo, “rather than lowering grades for undergraduate study and expecting them to cope”, it gives the students a year of support, both academic and personal (there is a dedicated welfare role in the team), before they join the undergraduate student body.

Over the course of the academic year, students not only receive teaching in their chosen subject (in Humanities, Law, PPE, or CEMS (Chemistry, Engineering, and Material Science) ), they also undertake a Preparation for Undergraduate Studies course. “It’s thinking about what academic skills they might require and recognising they may need support in order to thrive on an undergraduate course,” Jo says, “but also helping them build that sense of belonging in an academic institution like Oxford, which has its own nuances and distinct learning environment and can be quite a big step for some students.”

Chemistry student Yihao during his first term as an Astrophoria student at Oxford

Chemistry student Yihao during his first term as an Astrophoria student at OxfordThe first Astrophoria students arrived last September for their Orientation Week, which, Jo says, was “really important for building that sense of belonging and starting to do some critical thinking, but in a slightly more playful way. It’s quite deliberately set up to get them to be engaged in asking questions and starting to build their confidence.”

The students are based across 9 Oxford colleges, coming together for different aspects of the course and events. So how well have the cohort integrated into the wider student body? “We were a bit nervous about that” says Jo, “but, it hasn’t been an issue – they’ve been embraced by their colleges and just treated like any other student”.

A dedicated Outreach Officer in Jo’s team visits schools to build awareness of the Astrophoria programme among teachers and students. The reaction is overwhelmingly positive: “There’s quite often – more from the teachers – ‘oh, this really is as good as it sounds’”.

The team are focused on ensuring that eligible applicants feel motivated to apply. “There are still some students who think that Oxford’s not going to be for them, but it’s nice to begin to build our cohort of students who’ve been through the programme, to be able to use their voices to go back to schools so that they can try and dispel some myths about who Oxford is for.”

Astrophoria students speak about their experiences at an event in Oxford

Astrophoria students speak about their experiences at an event in OxfordReflecting on the programme’s inaugural year, Jo’s personal highlights come from the students and how they’ve developed, which she has seen first-hand through teaching as part of the Preparation for Undergraduate Study courses. “Some students in the first term are very nervous, very shy, very unsure and they’ve just grown in confidence and engagement in talking about things.”

A recent assessment in which the students presented posters addressing an academic question was a particular high point: “For me, the energy just really summed up the Astrophoria year. There were 22 students talking animatedly about an academic topic they were interested in, and they were energised but also supportive of each other and explaining their work to one another. Essentially that’s what we’ve been trying to build – we talk about a community and support network, an excitement in the academic work that they’re doing, and a willingness to present things."

Another ‘proud mum’ moment, as she calls them, came at an event with the Astrophoria donor. “Two of the students gave speeches and you just felt ‘wow’. They'd only been here a term but were happy to stand up and speak at an event”.

Have there been any surprises this year? Nothing major, she says, but “dealing with 22 young people there’s always something!”. Inevitably, says Jo, the programme will evolve as lessons are learnt, and the goal is to steadily increase the number of Astrophoria students over the next few years. Some of this year’s cohort may not progress on to Oxford’s undergraduate courses, but Jo hopes they have all benefitted from the programme and their Oxford experience; “I want the students to feel empowered”, she says.

Find out more about the Astrophoria Foundation Year.

Malaria kills more than 600,000 people every year, and each year, World Malaria Day (25th April) raises awareness of what continues to be one of the world’s deadliest infectious diseases.

The theme for this year’s World Malaria is on health equity across the globe, and the challenges faced by vulnerable groups such as pregnant women and young children.

Philippe Guerin was a clinician before working with Médecins Sans Frontières across Asia and Africa. He is now Professor of Epidemiology and Global Health at the University of Oxford, with a special interest in malaria. His work has provided evidence to support changes in the World Health Organization’s treatment guidelines for malaria.

'Malaria treatment guidelines are developed for the general population, but are rarely tailored for vulnerable subpopulations such as babies, pregnant women, and patients with comorbidities such as malnutrition, or HIV co-infections,' says Professor Guerin.

'It is imperative to develop optimised approaches for these groups too, to give them the best treatment for them. This is what is called precision public health.'

This is not because health authorities do not recognise the vulnerabilities these groups face - it is because there just wasn’t enough data to make clear recommendations. Vulnerable groups such as young children, pregnant women, or patients suffering from concomitant comorbidities are rarely included in clinical studies for a number of reasons, including ethical or safety concerns, costs, and recruitment challenges.

The problem is compounded by the fact that they are far fewer clinical studies of health conditions that affect the global south, compared to diseases that affect economically richer countries.

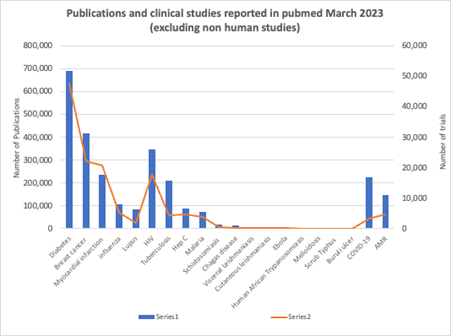

Figure 1: A graph comparing the number of published studies and clinical trials on different diseases. Diabetes, cancer, myocardial infarctions (heart attacks) are bigger concerns in the global north, while diseases such as malaria, schistosomiasis, chagas, Ebola, etc, affect populations almost exclusively in the global south.

Answering new research questions from existing data

'When it comes to diseases in resource limited settings, data are scarce and scattered: the number of scientific publications for something like diabetes is about 10 times that for malaria,' points out Professor Guerin.

One way to get around to this problem is to club together clinical data from individual patients into a larger, single dataset. Doing so can produce policy-changing scientific evidence from existing data, essentially allowing researchers to answer new scientific questions from old data.

The power of this approach was illustrated by a recent study led by Professor Guerin, which found that antimalarial treatments are more likely to fail in children with acute malnutrition.

'Malaria and malnutrition both affect poorer communities with limited research resources, so there just aren’t enough studies on the efficacy of antimalarial drugs in malnourished children, and past studies have contradictory results,' says Professor Philippe Guerin. 'So we used a different strategy to answer this question.'

The research team pooled individual patient data from 36 different antimalarial efficacy studies from 24 countries, that included body measurements (including height and weight) for the study participants. Using this information about weight versus height and age, the researchers could infer which children were likely to be malnourished (acute and chronic), and track outcomes specifically for this group.

'No one individual study included a large enough sample of malnourished children to uncover a clear relationship, but by combining information across many different studies, which each included few malnourished children, we were able to spot a clear pattern,' said Guerin.

'Clinical trial data have potentially bigger value than a single use'

This approach of combining data from many studies and then reusing it to answer new research questions, was pioneered by the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN), which brought together hundreds of scientists from more than three hundred institutes to pool their knowledge – and to identify gaps in this knowledge.

Established in 2009, Professor Guerin was WWARN’s first Director, and led a group of scientists attempting to bypass some of the unique challenges of malaria clinical research: 'Security concerns and pollical instability can often make it difficult or impossible to carry out a clinical trial in many countries affected by malaria. Limited resources in health systems can also make it difficult to enrol a representative sample of patients, as many patients aren’t able to access healthcare, making them invisible to clinicians,' says Professor Guerin.

'All of this means that clinical research in diseases of poverty often has relatively small sample sizes. This makes it harder to identify risk factors for patients, as these risk factors are relatively rare: if you’re only looking at a few patients, you might not have one of these rare patients, or you might not have enough of these patients to spot a pattern' says Professor Guerin. 'It was only be assembling lots of data together, under the aegis of WWARN, that we were able to understand what was happening in populations at risk for malaria.'

WWARN’s work identified that the standard dose of an otherwise effective antimalarial treatment, was actually too low for children under five for the combination dihydroartemsinin-piperaquine. This finding led the WHO to revise its official treatment guidelines.

Similarly, WWARN’s work on malaria in pregnancy has provided strong evidence to support WHO’s guidelines for malaria treatment for pregnant women, which were initially based on a much weaker evidence base.

This approach of clubbing together existing data also gets around the much more limited funding for studying diseases that largely affect people in the global south.

'Running a clinical trial can be 20 times more expensive if not more than clubbing together existing data and analysing it to answer the same research question,' says Professor Guerin. 'Clinical data here is scarce and precious – when the primary analysis is completed, there is an opportunity for maximising the added value of existing data.'

Equity in research

WWARN’s success showed that it was possible to produce policy-changing scientific evidence from existing data, and in 2016, the Infectious Diseases Data Observatory (IDDO) extended the same approach to other tropical infectious diseases.

Headed by Professor Philippe Guerin, IDDO’s main staff headquarters is in Oxford University’s Old Road Campus. IDDO promotes the reuse of individual patient data across the global infectious disease community, especially for malaria.

With over 15 people in the data management team alone, IDDO curates data that scientists across the world submit, harmonises them and connects them up with other datasets, and then makes the data available for free to any researcher, enabling scientists to answer new research questions from existing data.

It is particularly keen that research is led and informed by scientists and communities that are actually affected by the diseases: more than half of the IDDO curated data are used for individual patient data meta-analyses led by researchers from low and middle income countries, across Africa, Asia and Latin America.

IDDO also hosts TDR fellows, as part of a WHO career development programme which places researchers from disease-endemic countries with research organisations, to develop clinical research skills – IDDO will be welcoming two new TDR fellows this year. It also works with a number of institutions based in endemic regions including the Wellcome programmes in Asia and Africa, the EDCTP network of excellence (which brings together 15 European and 25 African countries), and the Indian Council of Medical Research to provide training.

'Tackling a disease like malaria needs many different kinds of expertise from many different places, and it is great to be working on a platform that brings many different kinds of scientists, from many different places, together', Professor Guerin says.

Find out more about IDDO’s resources to support malaria research on iddo.org/wwarn.

Professor Kamaldeep Bhui of Oxford's Department of Psychiatry, and former Editor-in-Chief of the British Journal of Psychiatry, explains the importance of editorial independence in promoting good science.

Given the contested nature of much mental health and brain research, it has never been more important for research in this area to be of the highest quality and observing the principles of research integrity and publication ethics. In so doing we ensure the production of knowledge does not bias the findings towards compounding health inequalities, with adverse policy or practice impacts.

As a psychiatrist and former editor of a scientific journal, I believe that editorial independence, through robust practice of publication ethics and research integrity, promotes good science and prevents bad science.

When editorial independence is challenged, we should all be concerned. This is why, together with senior members of the editorial team, I wrote an editorial for the British Journal of Psychiatry, the journal for which I used to be Editor-in-Chief.

Editorial independence in journals can be defined as editors having the freedom to make decisions about the scientific publication record. To promote good science, editorial independence must be non-negotiable for all scientific journals seeking to prevent influence from their owners or from groups with vested interests.

However, editorial independence is a multidimensional, dynamic, and complex concept that is often constructed in our responses to new and emerging challenges.

In the editorial, I outlined that too much published research is unsound with up to 10% of large-scale randomised trials suffering from major flaws. Corrections and retractions are one solution and should not be stigmatised. Rather they should be an accepted part of the contract between authors and editors, and a wider group of stakeholders. All should work in trust to establish and correct the scientific record on which public policy and practice can improve.

Dealing with older papers is especially complex. Scientific knowledge is contextual. Dismissing ‘old’ research entirely based on modern standards may overlook their incremental contributions. However, older papers should be appraised and judged against best practice at the time of publication; if found to be flawed in some fundamental scientific way, removal from the scientific record is appropriate.

Poor studies remain in the scientific record. There are hardly any requests for correction or retraction of uninfluential or uncited papers. Therefore, there is often a pressure to not retract a paper which is contributing to controversy and debate, as it rather perversely raises the profile of a journal. Indeed, many retracted or unretracted discredited papers continue to be highly cited.

Some larger publishers take charge of complaints, potential retractions, and any legal threats rather than following the guidance on editorial independence. This risks vested non-scientific interests becoming the basis or appearing to be the basis for decisions about flawed science.

An alarming trend is the use of legal threat to strategically control the publication and dissemination of public scientific findings. Legal challenges to editorial independence are especially difficult as settlements can be costly. To avoid this risk, owners may choose to neglect editorial decisions and undermine editorial independence. Our wider duties must also consider standards in public life and our respective professional values and codes of conduct.

When there are complaints or allegations of error, it is critical that the editor and author discuss potential remedies, for example corrections, re-analysis, the reporting and interpretation of the findings. This step should precede any discussion of potential retraction. When retraction is necessary, this should be mutually agreed if possible. A mutually satisfactory decision to retract may not be possible if authors object, or worse, if they resort to legal threat, thereby blocking any meaningful dialogue about the validity of their research.

As a former Editor in Chief and researcher myself, I know that the most important quality-control mechanism for research integrity is editorial independence guided by publication ethics to ensure that there is an uncompromising insistence on meeting the highest standards of scientific research, reporting and publication. Only then can improvements in practice and policy be grounded in science rather than vested interests.

Compliance with best practice guidance varies. Therefore, in our editorial, we suggested how we could protect and strengthen editorial independence. For example, regulation could include a register of breaches and scrutiny to learn lessons, as well as provision for legal advice on issues of public interest. Compliance with guidance, and adequate insurance and transparency must accompany the reconciliation of ethical and legal dilemmas. Scientists might disagree, the public and organisations representing specific positions might disagree; but the whole health industry from researcher, policy maker, to journal owners and editors must ensure they are capable and competent to fulfil obligations to protect editorial independence. Mapping policy and practice impacts of breaches, transparent processes for noting legal threats, and ethical leadership must sit alongside robust governance to support publication ethics and the principles and guidance on editorial independence.

- ‹ previous

- 2 of 249

- next ›

Oxford's student voices at COP29

Oxford's student voices at COP29 Teaching the World’s Future Leaders

Teaching the World’s Future Leaders  A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future

A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance

Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance

The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance  The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham

The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham  Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year

Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life