Large-scale fossil study reveals origins of modern-day biodiversity gradient 15 million years ago

Researchers have used nearly half a million fossils to solve a 200-year-old scientific mystery: why the number of different species is greatest near the equator and decreases steadily towards polar regions. The results – published today in the journal Nature – give valuable insight into how biodiversity is generated over long timescales, and how climate change can affect global species richness.

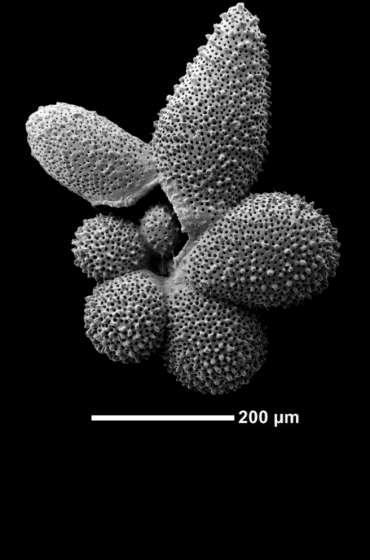

A scanning electron microscope image of the shell of the planktonic foraminifera species Globigerinella adamsi. This specimen was collected from sea floor sediments in the Southwest Indian Ocean aboard the GLOW Cruise. Image credit: Tracy Aze, University of Leeds.

A scanning electron microscope image of the shell of the planktonic foraminifera species Globigerinella adamsi. This specimen was collected from sea floor sediments in the Southwest Indian Ocean aboard the GLOW Cruise. Image credit: Tracy Aze, University of Leeds.This new study, led by researchers at the University of Oxford’s Department of Earth Sciences, used a group of unicellular marine plankton called planktonic foraminifera. The team analysed 434,113 entries in a global fossil database, covering the last 40 million years. They then investigated the relationship between the number of species over time and space, and potential drivers of the latitudinal diversity gradient, such as sea surface temperatures and ocean salinity levels.

Key findings:

- The modern-day latitudinal diversity gradient first started to emerge around 34 million years ago, as the Earth began to transition from a warmer to cooler climate.

- This gradient initially remained shallow, until around 15–10 million years ago, when it steepened significantly. This coincides with a significant increase in global cooling.

- Peak richness for planktonic foraminifera occurred at higher latitudes from 40–20 million years ago. By around 18 million years ago, however, peak richness shifted to between 10° to 20° latitude, consistent with the diversity pattern observed today.

- There was a strong positive relationship between species richness and sea surface temperatures – both when modelled over time at specific locations, or at different locations at a specific time.

- There was also a positive relationship between species richness and the strength of the thermocline: the temperature gradient that exists between the warmer mixed water at the ocean's surface and the cooler deep water below.

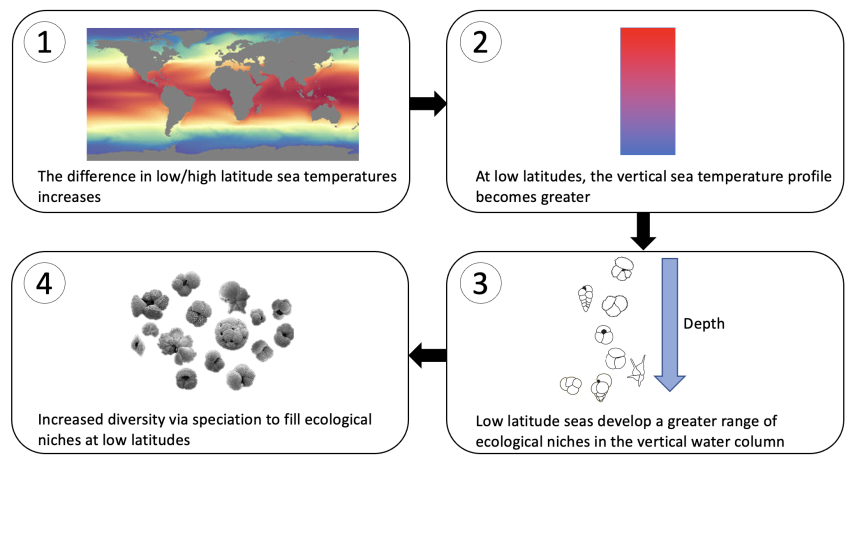

According to the researchers, these results indicate that the modern-day distribution of species richness for planktonic foraminifera could be explained by the steepening of the latitudinal temperature gradient from the equator to the poles over the last 15 million years. This may have opened up more ecological niches in tropical regions within the water column, compared with higher latitudes, promoting greater rates of speciation.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers examined the extent to which modern species of planktonic foraminifera live at different depths within the vertical water column. They found that in low latitudes closer to the equator, species today are more evenly distributed vertically within the water column, compared with high latitudes.

By resolving how spatial patterns of biodiversity have varied through deep time, we provide valuable information crucial for understanding how biodiversity is generated and maintained over geological timescales, beyond the scope of modern-day ecological studies.

Dr Erin Saupe (Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford), lead author for the study.

This suggests that a key driver of the modern-day diversity gradient was a significant increase in the difference in sea surface temperatures between low- and high-latitude regions, and within the water column, from 15 million years onwards. The warmer waters at the tropics were able to support a broader range of different temperature habitats and ecological niches within the vertical water column, encouraging higher numbers of species to evolve.

This is supported by the fact that the tropics today are richer than the tropics of warmer time periods in the past (such as the Eocene and Miocene) when there was little or no vertical temperature gradient in the oceans.

In addition, cooling sea temperatures at high latitudes likely caused many regional populations of species to become extinct, contributing to the modern diversity gradient.

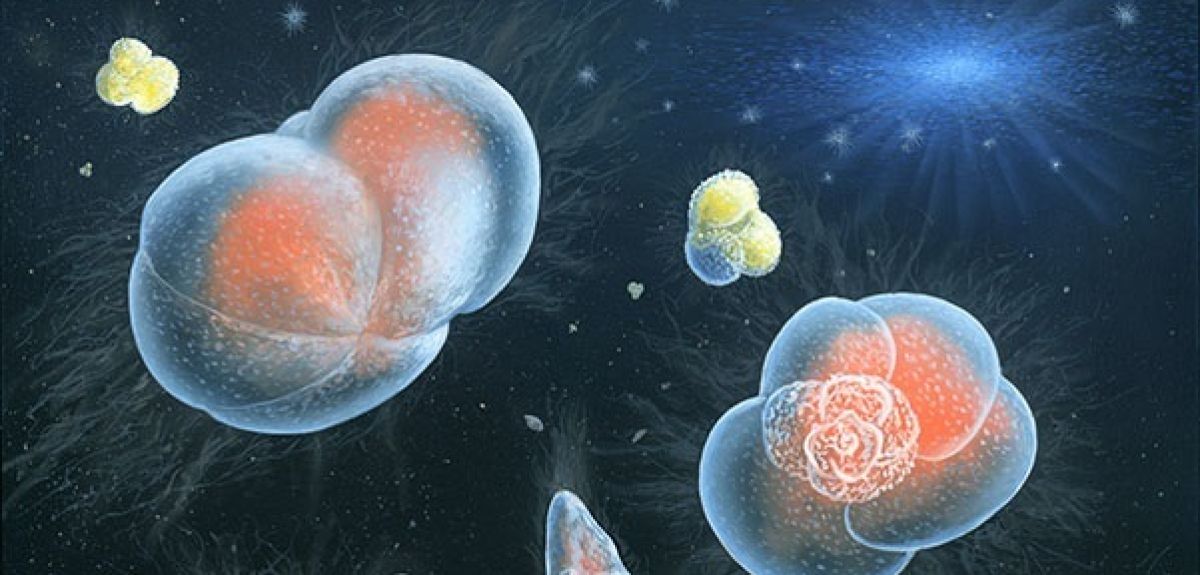

A light microscope image of a planktonic foraminifera (bottom right) surrounded by thins strands of its cytoplasm that extend into the surrounding environment. This living specimen had recently been collected from the water in the Southwest Indian Ocean aboard the GLOW Cruise. Image credit: Tracy Aze, University of Leeds.

A light microscope image of a planktonic foraminifera (bottom right) surrounded by thins strands of its cytoplasm that extend into the surrounding environment. This living specimen had recently been collected from the water in the Southwest Indian Ocean aboard the GLOW Cruise. Image credit: Tracy Aze, University of Leeds.Dr Erin Saupe (Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, lead author for the study, said: 'Planktonic foraminifera arguably have one of the most complete species-level fossil records of any group of organisms. Our study builds on decades of important research to uncover how planktonic foraminiferal distributions have changed across space and through time. It’s a privilege to synthesize these data to propose something fundamental about the drivers of ecological and evolutionary change.'

The paper ‘Origination of the modern-style diversity gradient 15 million years ago’ has been published in Nature. The study also involved researchers from the Universities of Bristol and Leeds.

Diagram to show the potential climatic processes that led to the modern-day latitudinal biodiversity gradient in planktonic foraminifera. Foraminiferal images adapted from Kearns et al. 2021.

Diagram to show the potential climatic processes that led to the modern-day latitudinal biodiversity gradient in planktonic foraminifera. Foraminiferal images adapted from Kearns et al. 2021. New Year Honours 2026

New Year Honours 2026

New study estimates NHS England spends 3% of its primary and secondary care budget on the health impacts of temperature

New study estimates NHS England spends 3% of its primary and secondary care budget on the health impacts of temperature

International collaboration launches largest-ever therapeutics trial for patients hospitalised with dengue

International collaboration launches largest-ever therapeutics trial for patients hospitalised with dengue

Oxford-built multi-agent assistant for cancer care to be piloted in collaboration with Microsoft

Oxford-built multi-agent assistant for cancer care to be piloted in collaboration with Microsoft