Atmospheric rivers could increase flood risk by 80 per cent

The global effect and impact of atmospheric rivers on rainfall, flooding and droughts has been estimated for the first time – revealing that in some regions the risks can be enhanced by up to 80 percent. The work, of which Oxford University is a key partner, also considers the number of people affected by these atmospheric phenomena across the globe.

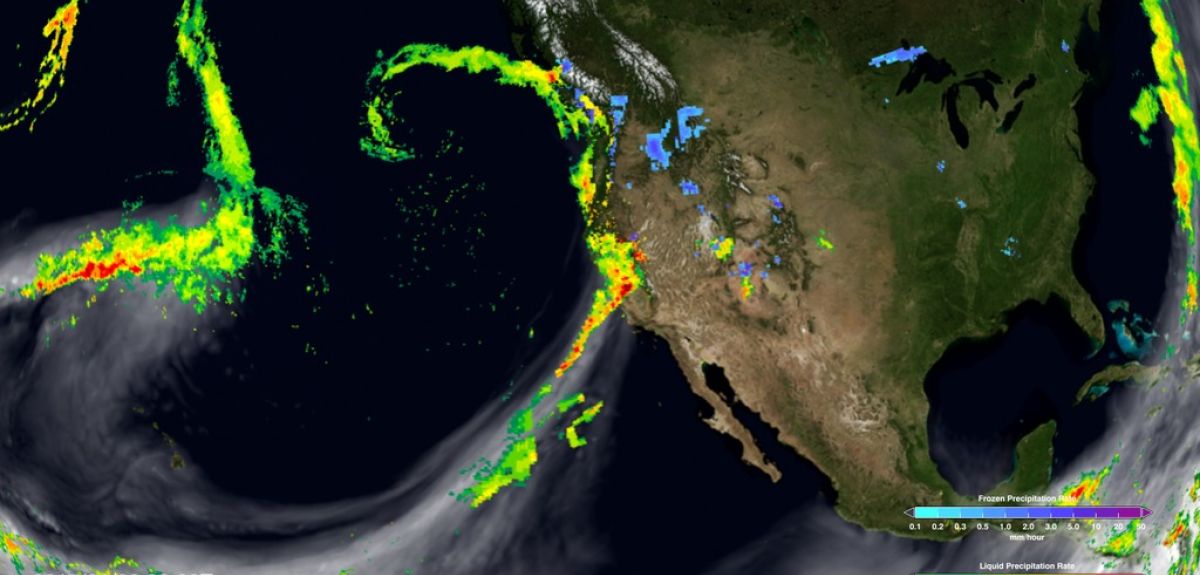

Atmospheric rivers get their name because they look like rivers of vapour in the sky. NASA, a collaborator in the research, defines them as relatively long, narrow, jets of air that can carry vapour as water, far and wide across some of the planet’s oceans, on to the continents and as far as the polar regions.

They are a form of extreme weather that can affect vast regions of the world, much like a tropical cyclone. The research estimates that, an average of almost 300 million people are exposed annually by flooding and droughts induced by atmospheric rivers. Although the percentage of the population affected by atmospheric river storms is comparatively small, they can still have significant impact.

Atmospheric rivers were initially thought to have a significant effect on precipitation, rainfall and flooding in specific global regions. However, this study is the first to assess how far the rivers affect global hydrology, and climate patterns.

The research revealed the jet streams’ impact to be quite profound. Precipitation from atmospheric rivers alone, contributes 22 percent of Earth’s total water flow. In some regions, particularly the east and west coast of North America, Southeast Asia and New Zealand, this can be more than 50 percent.

Globally, they were found to increase the likelihood of a flood or drought hazard – increasing the possibility of a flood by 80 per cent in areas where they were the most common. In those regions where rivers had the least influence, the chance of a drought increased by up to 90 per cent.

The team used a database of atmospheric rivers to build a picture of the volume of water generated, and the effect on stream flow, soil moisture and snow levels. They were then able to identify areas where this contribution has a major influence on flooding and droughts. This information was then used to calculate the number of people affected by these hazardous conditions.

Homero Paltan, the study’s lead author and a researcher at Oxford’s School of Geography and the Environment, said: ‘By incorporating demographic data into our study, we have found that, globally, a large number of people are exposed to hazards that stem from atmospheric rivers. They have a considerable impact that we're only beginning to understand and measure.’

Homero suggests that these observations should be incorporated into water resources and risk management. He adds: ‘How beneficial or damaging the effects of atmospheric rivers depends on how well we use the information we have to generate informed decisions. The nature and impacts of atmospheric rivers should be fed back to policy makers, risk insurers and water resource managers. For example, several sectors in California have already developed successful examples of institutional, operational and infrastructure adaptation strategies to this source of variability.’

Duane Waliser, chief scientist of the Earth Science and Technology Directorate at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California and the paper’s co-author, said: ‘This new work quantifies the potential impacts of atmospheric rivers on important freshwater quantities, such as snowpack, soil moisture and the occurrence of droughts and floods across the globe. The findings provide added impetus for considering improvements to our observing and modelling systems that are used for forecasting atmospheric rivers.’

The research was published in Geophysical Research Letters, and conducted by scientists from the Oxford University School of Geography and Environment, in collaboration with NASA and several other partners.

New Year Honours 2026

New Year Honours 2026

New study estimates NHS England spends 3% of its primary and secondary care budget on the health impacts of temperature

New study estimates NHS England spends 3% of its primary and secondary care budget on the health impacts of temperature

International collaboration launches largest-ever therapeutics trial for patients hospitalised with dengue

International collaboration launches largest-ever therapeutics trial for patients hospitalised with dengue

Oxford-built multi-agent assistant for cancer care to be piloted in collaboration with Microsoft

Oxford-built multi-agent assistant for cancer care to be piloted in collaboration with Microsoft