From punk rock to plants: Robert Scotland argues we need hard science to 'save' the natural world

Nature matters, not just because of the price some economist puts on it, or because of fashionable theories about how valuable it is for humans [the species which has done most to eradicate it], just because. Professor Robert Scotland should know. The Oxford professor of Systematic Botany (and his team) are natural (no pun intended) successors to the giants of his field, such as Robert Morison and Charles Darwin, whose careful taxonomic monographic science led to...you know the rest.

Professor Scotland has spent more than three decades at Oxford on painstaking research, in the tradition of Darwin and other monographers, working out the taxonomy of plant species to discover what exists, where are they found and how are they related. It may not be new science, but up-to-date DNA technology and other modern tools bring a unique perspective to our understanding of the natural world not offered by other subjects. And...it is key.

The 63-year-old Glaswegian looks genuinely upset at the idea that hundreds of thousands of plants have not been identified or catalogued properly – and, given the prevailing trends away from such work, may never be.

We simply do not know what is out there, he says, what benefits they might bring, what they can tell us about our world and what risks some might pose. And to some extent we have given up prioritising this type of research.

We simply do not know what is out there, what benefits they might bring, what they can tell us about our world and what risks some might pose. And to some extent we have given up prioritising this type of research

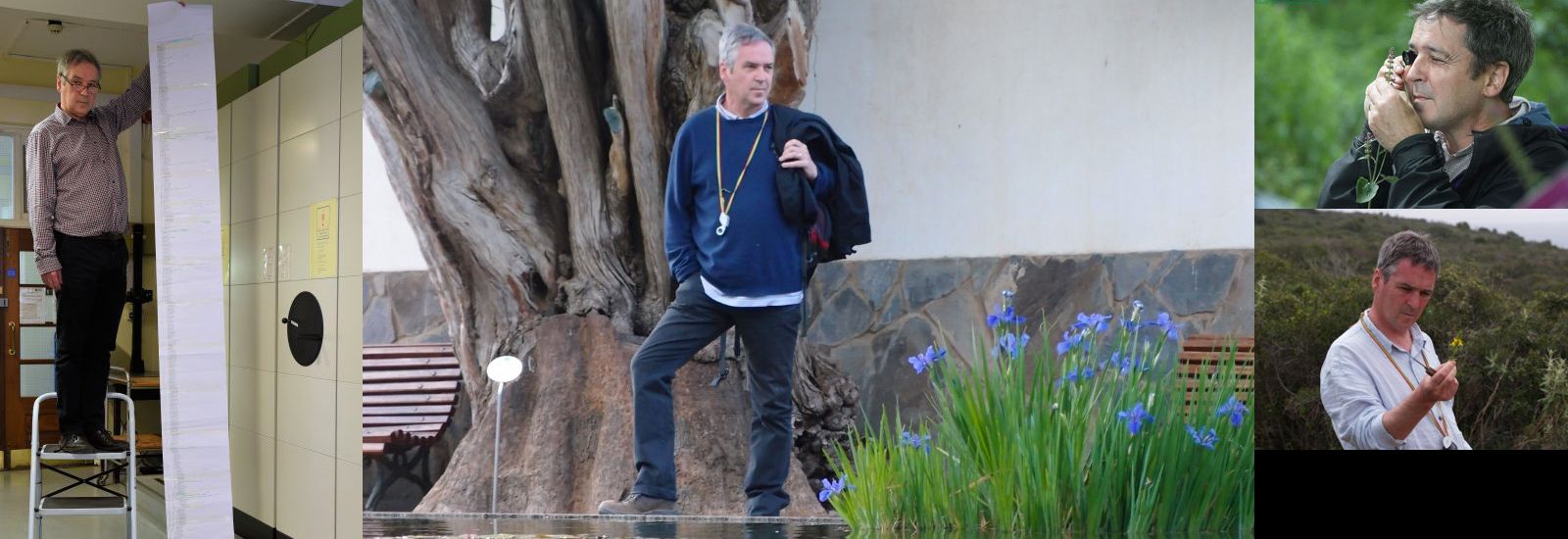

Professor Robert Scotland

Clearly passionate about his work, Professor Scotland looks unhappy at the very thought of all those wrongly catalogued plants, ‘There have been a million flowering plant names published but we estimate that six out of every 10 names are synonyms (multiple names for the same entity) and these synonyms have still to be worked out for many tropical plant groups. Our research has recently demonstrated that more than half of the world’s natural history collections have an incorrect name.’

Just before the pandemic, Professor Scotland completed a five and a half year project, a landmark Monograph of the Ipomoea genus – or ‘Morning Glories’, which includes the sweet potato.

It was a major undertaking and received plaudits from plant scientists around the world, full of praise for the research and the conclusions they were able to draw. Aside from plotting a species-rich group of tropical plants, including a crop, he and his team discovered, in no particular order:

- 70 new species;

- Two new species closely related to sweet potato (Crop relatives);

- A five-fold increase in the number of species in Bolivia from 22 to 109;

- Root tubers evolved not only in sweet potato but in more than 60 other species of ipomoea.

- Demonstrated that the sweet potato evolved in pre-human times and so is not solely a product of human domestication

- Species of Ipomoea managed to travel across the Pacific long before humans (sorry, Thor Heyerdahl).

How can we “save”, monitor or conserve the natural world, if we don’t know what is there? Not all of his conclusions were welcomed. There is something of an industry around the idea that seafaring Polynesians brought back the sweet potato to the south seas from the Americas. He says, ‘That’s what Thor Heyerdahl’s Kontiki expedition was all about proving. But we were able to show that these plants transport long distances without human intervention...it was probably long distance dispersal. It happens all the time.’

Professor Scotland is committed to the cause, an agitator for the natural world, who would more likely be seen on an Extinction Rebellion demo than at a prawn cocktail event for financiers

But, with interest in such careful science waning and little support, in the face of the green-juggernaut, he says it currently takes on average of 30-40 years from a specimen being first collected to it being recognised as a new species, and more than 100 years from first collection to having 15 accurately labelled specimens of that species. These lags reflect a chronic lack of capacity and training in basic knowledge of biodiversity.

'Our approach has been to develop a method to accelerate the pace of taxonomy in poorly-known groups of tropical plants’.

Professor Scotland is committed to the cause, an agitator for the natural world, who would more likely be seen on an Extinction Rebellion demo than at a prawn cocktail event for financiers. He has been here before. As a teenager, the young Robert was an idealist, looking for big solutions to the world’s problems.

‘I had a very Utopian view of the world,’ he says. ‘I wanted the world to be a better place.’

He was a young activist and had been the National Organiser for the National Union of School Students which, back in the 1970s, was a force with which to be reckoned.

In that decade and the next, the worlds of politics and popular music collided explosively, as punk and New Wave saw a generation dream of rebellion and reject slick, packaged music.

The young Robert did not just wear the lapel badges, he really did rebel....he lived in a Camden squat and devoted his time to the Anti-Nazi League, Rock against Racism, and spent days (and nights) on demos at the South African embassy....He was quite literally living the 1980s’ teenaged dream

‘It was a very interesting time,’ he says. ‘There was a real sense of social change and a real hope that things were going to change with music as well.’

Unlike most, the young Robert did not just wear the lapel badges, he really did rebel. To his parent’s dismay, aged 18, he did not become the first member of his family to go to university. Eschewing a place to study Maths and Physics at Edinburgh, he headed for London, where he lived in a Camden squat and devoted his time to the Anti-Nazi League, Rock against Racism, and spent days (and nights) on anti-apartheid demos at the South African embassy. And he worked for six years at Rough Trade records. He was quite literally living the 1980s’ teenaged dream.

Today, there would be a film about him. But thanks to YouTube, there are glimpses of his golden youth, when he appeared on Top of the Pops as the bassist for Scritti Pollitti, the post-punk band (big hair and high voices), named in homage to an Italian Marxist (it was the 1980s). And a youthful Professor Scotland can be seen dancing enthusiastically as the zoot-suited bongo player, on instrumental band, Pig Bag’s TOTP appearance.

He laughs as he reveals that every couple of years students ‘discover’ he was in a band and he goes from the least fashionable academic to the coolest (or whatever the word is), ‘There’s this YouTube video of Pig Bag. I was wearing a zoot suit. I was really into Kid Creole. And there were Fair Isle socks knitted by my granny in my top pocket. My sister recognised the socks before she realised it was me.’

He may no longer sport a zoot suit, but it completely blows any chance of him posing as a dour Scot. Professor Scotland’s evident commitment to science, though, makes it appear as if he is talking about someone else’s life - although he admits to still listening to the music of his youth on an old Wurlitzer jukebox bought when he was 20.

Commitment is the key. Even while he was part of London’s music scene, Professor Scotland developed an interest in plants. He says, ‘Someone bought me a book on trees...I started to do bark rubbings with charcoal to identify them.’

From there, he took O level Botany at evening classes, and from there he finally brought some relief to his parents by going to university, aged 25, to study Botany.

‘I was fascinated by plants and the classification of plants,’ he says. He received a First and stayed at King’s College until 1987, when he applied for a PhD.

He was given the last British Museum studentship and spent the next few years at the Natural History Museum studying pollen grains through a scanning microscope. The images were spectacularly beautiful, he says, and Art students would come to his lab to see what they could copy from nature.

Even without climate change, the natural world is being destroyed at an accelerating rate, and we should tackle this with increased knowledge rather than diminished expectations...The natural world is not really providing an eco-system service...the problem is, with the economic view of nature, there is little intrinsic ‘value’ in a lot of bio-diversity

Professor Scotland

In 1990, post doctorate, he came to Oxford and Lincoln College as a junior research fellow. He was still, occasionally, appearing on TOTP, but no one seemed to mind. And the then Dr Scotland felt welcome. His appointment was a great relief to his parents, he recalls, ‘My father said he had always wondered who to cheer for in the boat race.’

The long haul and careful approach, funded in part by a Royal Society University Research Fellowship, has been key to the academic’s career. Professor Scotland maintains, ‘By looking at a group, an entire group of plants, you get a unique perspective of the natural world....what there is, where it comes from and how it is related to other plants.’

He adds, ‘You see patterns, if you do the taxonomy....It is a valuable and important way of looking at the natural world that is complementary to and as potent as other disciplines.

‘Even without climate change, the natural world is being destroyed at an accelerating rate, and we should tackle this with increased knowledge rather than diminished expectations’.

Professor Scotland says, ‘The natural world is not really providing an eco-system service...the problem is, with the economic view of nature, there is little intrinsic ‘value’ in a lot of bio-diversity...’

‘The prevailing and mainstream economic approach – Natural capital and what does it offer for human need- is an empty sterile view of the natural world: viewing it through the lens only of human need,’ he adds. ‘Ecosystem services really misses the point about everything that is extraordinary and wonderful about the natural world.

‘We’ve destroyed much of the natural world in the UK, only having 3% of original forest cover. And 95% of the flower meadows have gone, 90% of water meadows have been drained and we have at least 40 million fewer birds in the sky than we had in the 1960’s.’

The prevailing and mainstream economic approach...is an empty sterile view of the natural world: viewing it through the lens only of human need. Ecosystem services really misses the point about everything that is extraordinary and wonderful about the natural world

Typically confounding stereotypes and with a flash of the old politics, the Scot concludes with a cricketing metaphor, ‘We need to go on the front foot, if we are really concerned about the environment. We have a highly degraded natural world but our approach to saving parts of it would be greatly enhanced by improved taxonomic information and a realistic acceptance of what is happening in the world.

‘The idea behind the ecosystem services and natural capital approach is that somehow the market will wake up to the true value of biodiversity and all will be well. The data suggests this approach is not working.’

Although he has found himself a rebel (again), several of Professor Scotland’s former 15 PhD students stand testament to his impact – holding leading academic positions around the country, drilled and appreciative of the hard-science of plant taxonomy. A current BBSRC grant to him and his students, to search for the elusive wild form of sweet potato in South America demonstrate the utility of taxonomic research for contemporary topics such as food security.

And he is wondering if the return of undergraduates will mean the end of online lectures.

‘I worked really hard on my online lectures’ he says, standing outside Oxford’s plants department, where he has spent the last 30 years. ‘I think they were much improved ..and there was a lot less swearing in them.’

Pictures of Ipomoea, (from the top, Ipomoea Argentea, I. corymbosa, I. mendozea and I. crinicalyx) kindly supplied by Professor Scotland. Plus, black and white picture of pollen grains, also supplied by Professor Scotland.

By Sarah Whitebloom