Bold birds show 'live fast, die young' attitude

Birds previously identified as having a 'bold' personality return to their nests more rapidly after being faced with a threat than their 'shy' counterparts.

The finding comes from a study of wild great tits in Oxford's Wytham Woods which recorded the responses of 43 female great tits to a simulated threat during the breeding season and then compared the time it took for birds with shy or bold personalities to return to incubate their eggs.

A report of the research, undertaken by Ella Cole of Oxford University's Department of Zoology in collaboration with John Quinn, is published today in Biology Letters. I asked Ella about shy and bold birds, taking risks, and where personality and ecology collide…

OxSciBlog: How do you determine if birds have a 'shy' or 'bold' personality?

Ella Cole: We measure personality by temporarily taking birds into captivity and releasing them into a room containing five artificial trees. We then record how they explore this new space for eight minutes using a handheld computer.

Birds vary considerably in their behaviour in this test, with some bold individuals quickly exploring every corner of the room, and other, more cautious birds staying in one place for the majority of the test. If individuals are tested again, weeks, months or even years later, they tend to behave in a similar way.

Previous work in captivity has shown that great tits that explore more quickly in this test are also more aggressive, less wary of novel objects and more likely to take risks than slower exploring birds. We therefore use this test as a measure of 'boldness'.

OSB: How did you test the link between personality and risk-taking behaviour?

EC: We wanted to measure risk-taking behaviour in the context of reproduction to test whether bold and shy birds differed in the amount of risk they will take to protect their offspring. Birds are very vigilant for any potential threats at their nest which may endanger themselves or their young.

We measured risk-taking by attaching a small black and white flag, representing an unknown threat, to the roof of birds' nestboxes and recording the time it took for females to return to the nest and resume incubating their eggs. We then tested whether the time it took a bird to re-enter the nestbox could be predicted by their personality score.

OSB: What did your experiments reveal about this link?

EC: We found that relatively bold females were quicker than shy birds to resume incubation in the face of perceived risk, with some shy females not returning until the flag was removed. Although it is not known how long these birds would have stayed away if the threat had not been removed, we do know that tits can abandon their breeding attempts completely in response to novelty at the nest.

Our results therefore suggest that shy individuals may prioritise their own survival over that of their offspring, while bold birds do the opposite. These findings support the idea that different personalities may reflect different approaches to life, where bold individuals adopt a 'live fast, die young' strategy, while shy individuals are more cautious and reserve more of their resources for the future.

OSB: Why is understanding birds' personalities important for ecology/conservation?

EC: The existence of animal personalities has wide reaching implications for the study of ecology and evolution. The environment an individual experiences in its life - both in terms of habitat and who it interacts with - is largely determined by its behaviour. Personality has been linked to a wide range of important behavioural traits such as dispersal, habitat choice, social behaviour, feeding, and mate choice.

As a consequence knowledge of personality can help scientist understand how species invade new habitats, how information or diseases spread through groups of animals, the stability and growth rates of populations and ultimately how behaviours evolve. Knowledge of personality even has implications for conservation; in many species personality is related to reproductive success, meaning that conservation breeding programmes can target individuals with certain personality types.

OSB: How do you hope to explore birds' personalities in future research?

EC: One area we hope to explore further is how shy and bold personality types might differ in how they find food in the wild. Work in captivity suggests that shy individuals may be more thorough when searching for food, while bold animals search more quickly but also more superficially. However, very little is known about how personality influences natural foraging behaviour, despite the fact that foraging performance is well known to influence both survival and reproduction, and is therefore a likely mechanism linking personality to fitness.

You can follow the Wytham Woods tit population on twitter @WythamTits

A report of the research, entitled 'Shy birds play it safe: personality in captivity predicts risk responsiveness during reproduction in the wild', is published in Biology Letters.

Why males stray more than females

Why males stray more than females Sex, skinks, and personality

Sex, skinks, and personality Do elephants call ''human!''?

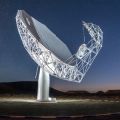

Do elephants call ''human!''? MeerKAT is shape of things to come

MeerKAT is shape of things to come How short is your time?

How short is your time?