Physically and culturally diverse human ancestors lived across Africa

It is widely accepted that the human race originated from Africa - likely from a single ancestral population. However, a new Oxford University research collaboration has challenged this perception of evolution, suggesting that instead of one group growing from a specific region in Africa, our ancestors lived across the entire continent, and as a result, people were diverse both physically and culturally, from the very beginning.

Led by Dr. Eleanor Scerri of the University of Oxford and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, the study, found that not only were humans scattered across Africa, but, due to a combination of diverse habitats and shifting environmental boundaries, such as forests and deserts, they did not really interact and were largely kept apart. As a result of this separation - which spanned more than a thousand years - the human species diversified and ultimately, this mixing of groups shaped the future of our species as we know it.

The research, published in Trends Ecology & Evolution, combines the study of bones (anthropology), stones (archaeology) and genes (population genetics) with detailed reconstructions of the changing African continent’s climate and general habitat, to build a different picture of our evolution over the last 300,000 years.

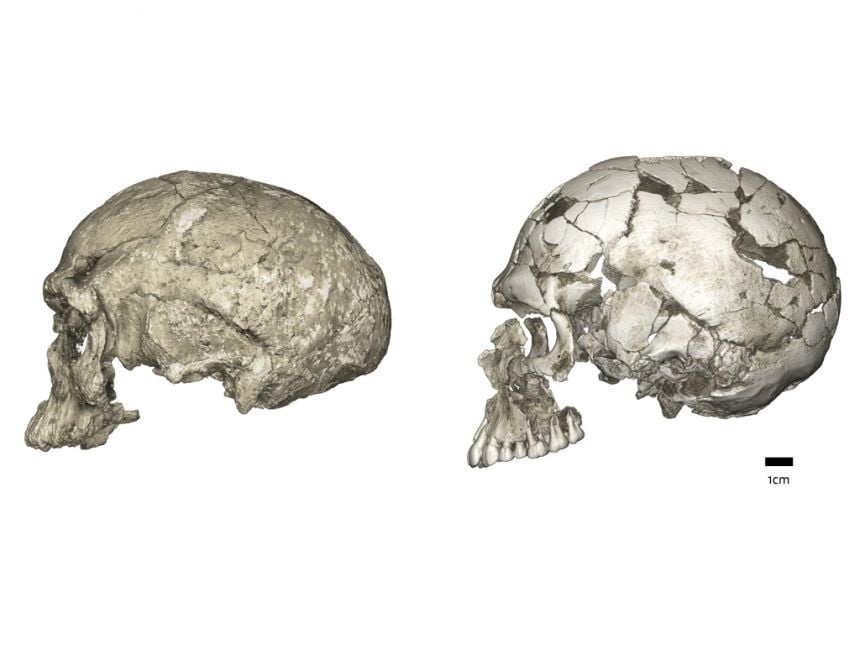

African skull from around 300,000 years ago Right: Skull from the Levant dating from around 95,000 years ago. image credit: Phillipp Gunz

African skull from around 300,000 years ago Right: Skull from the Levant dating from around 95,000 years ago. image credit: Phillipp GunzDr. Eleanor Scerri, lead author, British Academy postdoctoral fellow and a junior research associate at Oxford’s School of Archaeology and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, said: ‘Many had assumed that early human ancestors originated as a single, relatively large ancestral population, and exchanged genes and technologies like stone tools in a more or less random fashion. However, Stone tools and other artifacts – usually referred to as material culture – have remarkably clustered distributions in space and through time. While there is a continental-wide trend towards more sophisticated material culture, this ‘modernization’ clearly doesn’t originate in one region or occur at one time period.’

The human fossils found support this conclusion, Professor Chis Stringer, co-author and researcher at the London Natural History Museum, added: ‘When we look at the morphology of human bones over the last 300,000 years, we see a complex mix of archaic and modern features in different places and at different times.

‘As with the material culture, we do see a continental-wide trend towards the modern human form, but different modern features appear in different places at different times, and some archaic features are present until remarkably recently.’

Completing the research picture, the genetic analysis tell a similar story, as Professor Mark Thomas, a co-author on the study and geneticist at UCL, explains: ‘It is difficult to reconcile the genetic patterns we see in living Africans, and in the DNA extracted from the bones of Africans who lived over the last 10,000 years, with there being one ancestral human population. We see indications of reduced connectivity very deep in the past, some very old genetic lineages, and levels of overall diversity that a single population would struggle to maintain.’

Looking at the question of why human groups were so divided, and how this changed over time, the team used their climate and environmental analysis to better understand the shifting and often isolated habitats. Many of the most inhospitable regions in Africa today, such as the Sahara, were once wet and green, with interwoven networks of lakes and rivers, and abundant wildlife. Similarly, some tropical regions that are humid and green today were once arid. The shifting nature of these environments means that human populations would have gone through many cycles of isolation – leading to local adaptation and the development of unique material culture and biological makeup – followed by genetic and cultural mixing.

‘Convergent evidence from these different fields stresses the importance of considering population structure in our models of human evolution,’ says co-author Dr. Lounes Chikhi of the CNRS in Toulouse and Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência in Lisbon.'This complex history of population subdivision should thus lead us to question current models of ancient population size changes, and perhaps re-interpret some of the old bottlenecks as changes in connectivity,’ he added.

‘The evolution of human populations in Africa was multi-regional. Our ancestry was multi-ethnic. And the evolution of our material culture was, well, multi-cultural,’ said Dr Scerri. ‘We need to look at all regions of Africa to understand human evolution.’

Ethiopian wolves reported to feed on nectar for the first time

Ethiopian wolves reported to feed on nectar for the first time

Professor Anthony Harnden appointed as the new Chair of the MHRA

Professor Anthony Harnden appointed as the new Chair of the MHRA

Study of menstrual tracking app usage highlights potential role in improving access to reproductive health services

Study of menstrual tracking app usage highlights potential role in improving access to reproductive health services

Oxford establishes Ashall Professorship in Artificial Intelligence following Ashall donation

Oxford establishes Ashall Professorship in Artificial Intelligence following Ashall donation

Oxford launches new storytelling competition with management and production company, 42

Oxford launches new storytelling competition with management and production company, 42