Deep-sea wildlife more vulnerable to extinction than first thought

We have only known about the existence of the unusual yeti crabs (Kiwaidae) - a family of crab-like animals whose hairy claws and bodies are reminiscent of the abominable snowman - since 2005, but already their future survival could be at risk.

New Oxford University research suggests that past environmental changes may have profoundly impacted the geographic range and species diversity of this family. The findings indicate that such animals may be more vulnerable to the effects of human resource exploitation and climate change than initially thought.

Published in PLoS ONE, the researchers report a comprehensive genetic analysis of the yeti crabs, featuring all known species for the first time and revealing insights about their evolution. All but one of the yeti crab species are found on one of the most extreme habitats on earth, deep-sea hydrothermal vents, which release boiling-hot water into the freezing waters above above them.

The research was conducted by ecologists from Oxford’s Department of Zoology, Ewha Woman’s University, Seoul, South Korea and additional Chinese collaborators.

The results reveal that today’s yeti crabs are likely descended from a common ancestor that inhabited deep sea hydrothermal vents on mid-ocean ridges in the SE Pacific, some time around 30-40 million years ago.

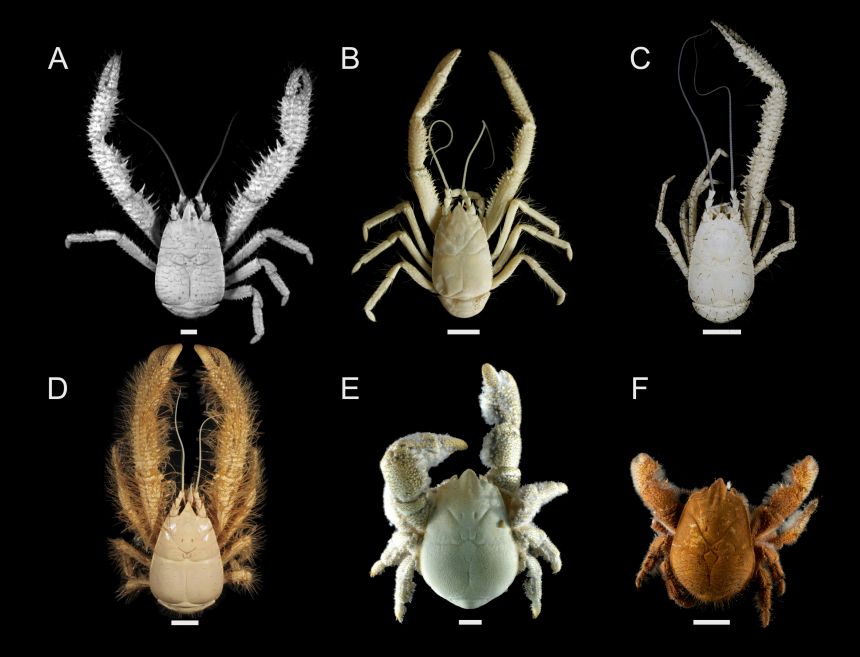

Fig 1 from the paper - photos from all known species of yeti crab

Image credit: C Roterman

Fig 1 from the paper - photos from all known species of yeti crab

Image credit: C RotermanBy comparing the location of current yeti crab species with their history of diversification, the authors suggest that the crustaceans likely existed in large regions of mid-ocean ridge in the Eastern Pacific, but have since gone extinct in those areas. While the reasons for this are unclear, the findings point to environmental changes, when a shift in deep sea oxygen levels was triggered by climate change and changes to hydrothermal activity at mid-ocean ridges.

Christopher Roterman, co-lead author and postdoctoral researcher in of Oxford’s Department of Zoology, said: ‘Using these genetic techniques, our study provides the first circumstantial case for showing that hydrothermal vent species have gone extinct in large areas. The present-day locations of these animals are not necessarily indicative of their historical distribution.

‘The findings have implications for our understanding of how resilient deep-sea hydrothermal vent communities might be to environmental change and the consequences of deep sea mining.’

Hydrothermal vents are just a small fraction of the deep sea environment. However, researchers are finding new species continuously and building a better picture of deep ocean life and its potential resources. Overtime these insights should help us to understand whether we can or should responsibly utilise them.

Roterman, who was also co-author of a study published last year, highlighting shocking gaps in our knowledge of deep sea environments, added: ‘Our understanding of deep sea ecosystems is still very basic and we need to adopt a cautionary approach to exploitation. Before we go bulldozing in, we need to more aware of not only what lives down there, but how resilient their populations are likely to be to human activity.’

Animals like the yeti crabs are potentially vulnerable to resource exploitation in the deep sea and I believe that humans, as a species, have a responsibility to preserve and steward our planet’s biodiversity as prudently and ethically as possible.’

The research was co-led by Won-Kyung Lee of Ewha Woman’s University, Seoul, Korea and supervised by Yong-Jin Won of the same institute.

Yeti crabs are named for their unusual hairy claws and bodies:

Professor Sue Iversen (1940–2025)

Professor Sue Iversen (1940–2025)

New study shows how AI can help prepare the world for the next pandemic

New study shows how AI can help prepare the world for the next pandemic

Lifestyle and environmental factors affect health and ageing more than our genes

Lifestyle and environmental factors affect health and ageing more than our genes

Lord Hague officially admitted as Oxford University’s Chancellor

Lord Hague officially admitted as Oxford University’s Chancellor

Lord Hague's Chancellor admission speech

Lord Hague's Chancellor admission speech