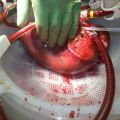

Kidney transplant drug halves the early risk of organ rejection

Oxford University scientists have shown that a drug given at the time of a kidney transplant operation halves the risk of early rejection of the organ. The drug, called alemtuzumab, also allows a less toxic regimen of anti-rejection drugs to be used after the operation.

The researchers have reported their results in the medical journal The Lancet and have presented their findings at the World Transplant Congress in San Francisco.

Kidney transplantation is still the best treatment for patients with kidney failure, but much more subtle approaches are needed if success rates are to be improved.

Around 2,000 people have a kidney transplant in the UK every year, and 15,000 people receive a transplant annually in the USA. Patients need to take drugs to suppress their immune systems in order to reduce the chances that their body will 'reject' the new kidney. It is a risky procedure since disabling the immune system in this way can lead to an increased number of infections and cancer.

Doctors are often faced with a difficult conundrum: using powerful combinations of treatments to prevent early kidney rejection can cause kidney damage later, and may subsequently be a cause of transplant failure.

These are important findings which we hope will guide treatments in the future

Professor Peter Friend

One of the main culprits is a class of drugs known as calcineurin inhibitors. These drugs are very effective at preventing rejection in the first weeks and months after a transplant, but their effects can have serious consequences for the kidney later on.

The 3C study, led by Oxford University scientists, tested whether the anti-rejection drug alemtuzumab with low-dose tacrolimus (a calcineurin inhibitor) could reduce transplant rejection when compared with existing treatment.

The study recruited 852 patients who had a kidney transplant in the UK between 2010 and 2013.

‘Our primary aim was to find out whether alemtuzumab-based induction therapy would produce worthwhile reductions in acute rejection,’ explains chief investigator Professor Peter Friend, from Oxford University’s Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, ‘but we also wanted to see whether we could use it with a lower dose of tacrolimus, because there is some evidence that tacrolimus contributes to long-term transplant failure.’

7.3% of those receiving the alemtuzumab-based therapy experienced early rejection of the organ, compared with 16.0% of those on basiliximab-based therapy – a halving in the risk of early rejection.

‘These are important findings which we hope will guide treatments in the future,’ said Professor Friend.

Although alemtuzumab has been available for many years, its use has been limited by concerns about possible side effects, in particular infections. But the scientists report that there was no increased risk of serious side effects – such as infections and cancer – among patients on the treatment.

Dr Richard Haynes of the Clinical Trial Service Unit at Oxford University said: ‘The safety data from the 3C Study are reassuring. There was no overall excess risk of infections or other known complications of immunosuppression.’

Professor Colin Baigent, one of the other lead investigators, said: ‘These results from the first six months of the 3C Study demonstrate the importance of large randomized trials in transplantation. The planned long-term follow-up of the 3C Study will provide a unique opportunity to investigate whether these differences in short-term outcomes translate into improvements in the long-term which will be of great interest to patients and their doctors.’

Professor James Neuberger, associate medical director at NHS Blood and Transplant, said: ‘NHS Blood and Transplant is delighted to be supporting this multi-centre UK study into the immunosuppression treatment of patients who have received a kidney transplant. We would like to congratulate the investigators on the good outcomes they are reporting and we hope these results will be sustained in the long term. Improving outcomes for patients and their families, will help us to achieve our aim to make every donation count and enable even more patients receive the transplants they need.’

The 3C Study was funded by a research grant from NHS Blood and Transplant and by grants from Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK and Pfizer. The study was designed, conducted, analysed and interpreted independently of the funders.

New study reveals the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on other causes of death

New study reveals the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on other causes of death

Researchers develop a way to test the ability of red blood cells to deliver oxygen by measuring their shape

Researchers develop a way to test the ability of red blood cells to deliver oxygen by measuring their shape

New study calls for radical rethink of mental health support for adolescents

New study calls for radical rethink of mental health support for adolescents

Oxford-led project awarded £2 million to revolutionise clean hydropower energy

Oxford-led project awarded £2 million to revolutionise clean hydropower energy

Botanists name a beautiful new species of ‘lipstick vine’ discovered in the Philippine rainforest

Botanists name a beautiful new species of ‘lipstick vine’ discovered in the Philippine rainforest

World first: device keeps human liver alive outside body

World first: device keeps human liver alive outside body